Article written by Joe Wolfinger and Chris Kerr, retired FBI Special Agents. They are the co-authors of RICO—How Politicians, Prosecutors, and the Mob Destroyed One of the FBI’s finest Special Agents.

H. Paul Rico was a good man, an outstanding public servant and an unsung American hero. He was the FBI agent who destroyed the highly profitable Raymond Patriarca Mafia organization in New England by sending Patriarca to jail twice. In the process, he helped create both the Witness Protection Program and the FBI use of informants, and plea-bargained testimony combined with electronic surveillance. —Alan Trustman, co-owner of World Jai Alai, Inc. and author of screenplays for several successful movies, including Bullitt and The Thomas Crown Affair

A Murder and a 22-Year Investigation

Wednesday was always Roger Wheeler’s day to play golf at Tulsa’s exclusive Southern Hills Country Club and May 27, 1981 was no exception. After a round of golf Wheeler showered, dressed, shared a drink with friends and walked to his car where two men sat in a late model brown sedan waiting to kill him. As he sat down in the driver’s seat of his car, one of the men, a heavyset, black-bearded man with dark sunglasses walked up to him and, without warning, shot him once in the face with a .38 caliber revolver. The shooter and his associate quickly fled the scene.

At the time of his murder, Wheeler was the owner of World Jai Alai, Inc., a sports/gaming organization based in Florida and H. Paul Rico, a retired FBI agent, was employed there as a vice president primarily responsible for security.

The initial investigation by the Tulsa Police was intense but failed to identify any suspects. Mike Huff, one of the original officers responding to the crime scene, would become the detective assigned to pursue the case. Over the next two decades Detective Huff learned that the trail led to Boston gangsters John Martorano, Whitey Bulger, Stevie “The Rifleman” Flemmi and their South Boston Winter Hill Gang.

By 2003 Flemmi and Martorano, the man who fired the fatal shot killing Wheeler, found themselves facing a wide array of criminal charges, including the murder of Roger Wheeler. Both sought a deal in which they offered to testify that Rico was in on their conspiracy and murder of Wheeler in exchange for leniency in their cases.

Flemmi said that from Boston in May 1981, after having had no contact with Rico since 1969, he telephoned the top-notch former OC agent cold at WJA in Miami. In that call, Rico, one of the Bureau’s pioneers in using electronic surveillance and cooperators to put high-level mobsters in prison, allegedly told Flemmi that Rico “and others” wanted Roger Wheeler murdered. The many wildly improbable aspects of this story apparently bothered prosecutors not at all.

Martorano’s only claimed connection with Paul Rico was a long-missing slip of paper with Wheeler’s personal information that Martorano claimed was passed to him by an intermediary in 1981. Unfortunately, the intermediary, John Callahan, was no longer available to corroborate any of this because Martorano murdered him about a year after he killed Wheeler. Martorano claimed that the intermediary, the long-dead Callahan told him the piece of paper came from Rico, who, prior to the murder had never spoken with Martorano.

In the fall of 2003, the elected Tulsa District Attorney Tim Harris and Detective Huff flew to Boston to make a deal with Flemmi. This fairly unusual direct involvement of the top prosecutor followed a public campaign by Huff to pressure Harris to charge Paul Rico in the Wheeler murder. Immediately after losing his battle to have his federal charges dismissed, Flemmi decided to flip and was anxious to make a deal; almost as anxious as Harris and Huff. What Flemmi wanted was no death needle in Oklahoma, a state which makes use of its death penalty, and he’d done enough research to know he wanted to do his time in federal prison instead of a state penitentiary. The extraordinary story these two Oklahoma lawmen were willing to buy betrayed their eagerness to believe what the gangsters were peddling.

By the time we interviewed him, Tulsa DA Harris had no recollection of the Boston AUSA providing some important information on Flemmi’s questionable credibility. In an earlier case before he secured Flemmi’s cooperation, the AUSA had filed extensive pleadings with the United States Court of Appeals arguing that he and a federal judge both believed Flemmi had committed perjury in federal hearings there and was not to be believed.

Harris and Huff returned to Tulsa and immediately had a friendly family court judge issue an arrest warrant for the 78-year old retired FBI agent. The probable cause depended heavily on Flemmi’s credibility: Huff’s affidavit stated Rico had operated Flemmi as an informant beginning in 1965 (without mentioning that Rico closed Flemmi in 1969) and then stated that in May 1981 “Flemmi says he had a phone conversation with Rico and that Defendant Rico confirmed that he and others wanted Mr. Wheeler killed.”

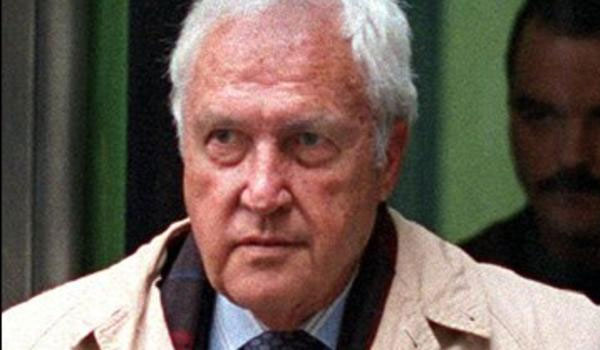

An Arrest and a Hearing

First-Degree Murder warrant in hand, Detective Huff immediately flew to Miami and on October 10, 2003, more than 22 years after the Wheeler murder, he led seven Miami officers in a 4:00 a.m. raid on the two-bedroom condominium of retired Agent Paul Rico. Huff pounded loudly on the door and when it was opened rushed inside and arrested Rico. While Huff’s demeanor seemed harsh and tough to witnesses, one of the Miami officers with him took note of Rico’s feeble condition suggesting to his wife, Connie, that he should be dressed warmly, eat something and she should prepare his medications to take with him. At the time of his arrest, Paul Rico had serious cardiac problems.

Paul Rico was held in a local Miami contract jail—one of the roughest in the area—for three months. Instead of being segregated from other prisoners as former law officers generally are, he was placed in general population. There he was attacked by inmates and severely beaten. In January, 2004, Rico was stable enough to be flown to Tulsa. On January 16th Garvin Isaacs, Rico’s defense attorney, pleaded for medical treatment for his client saying that he was seriously ill suffering with congestive heart failure. He asked the court for an emergency medical furlough so the 78-year old retired agent could be treated and prepare for his day in court. Paul’s wife Connie, a nurse, and two of his daughters, one a medical doctor and the other a lawyer also trained as a nurse, all testified that he had lost over 50 pounds since his arrest and that he was in grave condition and declining.

Isaacs requested that a shackle that bound Rico to his bed be removed. He said that there was no reason for the prosecution to oppose such a request unless it wished to inflict further pain and suffering. The idea that the frail, severely ill Rico was a flight risk or danger to anyone was ludicrous. Nevertheless, the prosecution objected and the judge ruled against the defense. Six hours later, Paul Rico died shackled to a bed.

The medical staff responsible for Rico’s treatment allowed him to become dehydrated, which, according to the autopsy report, caused his body to accumulate blood thinners and resulted in a fatal hemorrhage of his kidneys. It was a sad, tragic end brought about by a lethal combination of negligence, incompetence and mendacity—none attributable to Paul Rico. One medical expert reviewed the autopsy and commented that those responsible for his care, should have lost their licenses. The famously religious Tulsa District Attorney is said to have commented that the DA’s office had done its part and God had done His.

Who was Paul Rico?

Paul Rico was always an overachiever, a competitor, tough minded and determined. He loved competition, games and sports of every sort. As a teenager he transferred from a private parochial school to Belmont High School so he could play sports. A popular student, he became one of a losing team’s football stars. A local newspaper described his play at guard as “sensational.” In the fall of 1943, after football season was over, he dropped out of high school and joined the Army. During WWII a teenage Paul Rico served in Italy as a radioman and gunner in a B-24. He fought in the battles of the Po Valley, North Apennines and Rhineland and was awarded three bronze stars, interestingly, a fact he never shared with his family.

Paul Rico was always an overachiever, a competitor, tough minded and determined. He loved competition, games and sports of every sort. As a teenager he transferred from a private parochial school to Belmont High School so he could play sports. A popular student, he became one of a losing team’s football stars. A local newspaper described his play at guard as “sensational.” In the fall of 1943, after football season was over, he dropped out of high school and joined the Army. During WWII a teenage Paul Rico served in Italy as a radioman and gunner in a B-24. He fought in the battles of the Po Valley, North Apennines and Rhineland and was awarded three bronze stars, interestingly, a fact he never shared with his family.

After WWII Rico returned to Belmont, finished high school and resumed his relationship with his high school sweetheart, Connie. When he graduated, he went to Boston College on the G.I. Bill. While in college he was on the chess team that won the national Jesuit school chess championship.

When Paul Rico applied for the FBI in 1950, Connie, remembering the times they cut high school, did not think he would be selected. Director Hoover had high standards but, of course, skipping school occasionally was not the sort of thing that would prevent you from an FBI career. He was selected as an agent and completed new agents training on April 21, 1951. He married Connie on the same day he graduated and they moved to Chicago honeymooning in Niagara Falls on the way.

Rico spent a year learning the ropes as a new agent in Chicago and in March, 1952, was routinely transferred to Pittsburgh. Shortly after he arrived in Pittsburgh he learned that his father had inoperable cancer and was given only six months to live. Rico applied for a hardship transfer to Boston saying his wife was a trained nurse and could help his mother and he would have to assist his family financially. He was granted a hardship transfer at his expense and arrived in Boston where he would spend the next 18 years.

Four years after Rico began his FBI career, his work as an investigator prompted a supervisor to note that he had done “perhaps the most outstanding job of any agent in the office on the informant program.” This was high praise. Rico was assigned to one of the larger FBI offices and making substantial contributions to the work of many of its agents.

During the 1950s and 1960s Paul Rico contributed to Boston’s success in many areas. In the 1950s when the notorious Whitey Bulger was charged with bank robberies, Rico found and arrested him. Bulger was convicted and sentenced to 20 years in prison. In the 1960s Rico was assigned full time to develop informants. During this period he developed Joe “The Animal” Barboza as a cooperating subject. Barboza testified against several LCN figures and contributed immeasurably to the conviction of the New England Mob Boss, Raymond Patriarca for conspiracy to commit murder. Barboza was one of the first cooperating subjects to enter the Witness Security Program (WITSEC).

Rico also recruited John “Red” Kelley, regarded as a criminal mastermind and used by the LCN to plan murders and other crimes. Kelley’s successful testimony against Patriarca resulted in a second conspiracy to commit murder conviction for the mob boss. Kelley also provided information that resulted in the indictment of Carlo Gambino, head of the Gambino Crime Family and regarded as Boss of Bosses. By 1970 Rico had been so successful in Boston that the LCN made the unusual move of discussing a “hit” on the by-then well-known G-man. To lower the threat, Director Hoover offered to move Rico and his family anywhere in the country. Paul and Connie Rico chose Miami since it had better climate but was still on the East Coast where their Boston family and friends could visit occasionally.

Retirement

In 1975, after five years in Miami, Paul Rico retired and took the job of Vice President of World Jai Alai which was based in Florida and planned an expansion to Connecticut. The job was ideal for Rico. He had an expense account, company car, his country club dues were paid and he had company trips to Spain to watch jai alai players compete. His secretary at World Jai Alai dismissed the idea that Rico would participate in a conspiracy to murder the company’s owner commenting that he was happy and questioning rhetorically, “You have all this, and you’re going to kill (your boss)?”

WJA was owned by Alan Trustman and several others when Rico went to work there. Trustman had hired an innovative CPA, John Callahan, who was also from Boston to serve as president of the company. A year after Rico started working for the WJA, however, he learned that his boss, Callahan, had been seen hanging out while in Boston with mob hitman Johnny Martorano. Rico instantly did the right thing and brought the matter to the attention of the WJA board, which promptly fired Callahan.

Trustman and his fellow owners sold the company to Wheeler in 1978 and Callahan assisted Wheeler in the transaction. Specifically, Callahan designed a tax avoidance scheme in which Wheeler could value the contracts that WJA held with the jai alai players at $15 million and take a $5 million deduction each year for three years. Wheeler had a reputation as a “hard-bargainer” who would walk away from a deal unexpectedly at the last minute and speculation among some law enforcement circles is that Callahan was promised something by Wheeler who did not deliver and an angry Callahan asked Bulger and Flemmi to murder Wheeler. (Callahan himself was murdered by John Martorano in 1982.)

Following the murder of his father, Roger Wheeler, Jr., oversaw WJA operations, keeping Rico in place until he retired in 1997. Roger Wheeler, Jr. was fond of Paul Rico and does not believe that Rico had anything to do with his father’s murder. A photo of Rico playing golf is among the pictures of friends and associates that are in Wheeler’s office.

In 1981 the FBI needed an “old Bagman” (“older” at least than active FBI agents who, at the time, were required to retire at 55) to play the role of a mobster making a payoff in the investigation of US District Judge Alcee Hastings. Represented by a retired Organized Crime strike force attorney, Rico executed a personal services contract with the Bureau for his undercover role charging the FBI a total of $1 for his time-consuming undercover work. The Miami supervisor on the case had nothing but praise for Rico’s work. Hastings managed to beat the criminal case at trial, but he was impeached by the House of Representatives, convicted by the Senate and removed as a federal judge. Ironically, he now serves as an elected member of the House of Representatives.

A “Perfect Storm” Enveloped Paul Rico

One might ask how all of this could have happened to an FBI agent like Paul Rico. Our investigation led us to conclude that Rico found himself at the center of an almost “perfect storm.” Some very dark clouds formed with an extremely serious corruption probe centering on FBI Boston’s operation of Bulger and Flemmi as informants, focusing primarily on the late 1970’s and early 80’s, long after Rico’s tenure there. This was cleverly exploited by street-wise mob killers who spoon-fed credulous, naive investigators eager to substantiate an improbable prosecution theory involving the former agent. Flemmi and Martorano, who spent months in jail together, were smart enough to know that Paul Rico was their meal ticket.

While the corruption case led to public disclosure of criminal behavior by two FBI agents, John Connolly and his supervisor, John Morris, it also generated rumors and many inflated, overblown stories and claims that were not proved. When these stories turned to Rico they were complicated by the widespread—but unsubstantiated—assumption, pushed by a publicity-seeking Connecticut prosecutor that Jai Alai was intrinsically corrupt because gambling was involved.

In 2001 the House Committee on Government Reform held a series of high-profile hearings targeting what its then-Chairman Dan Burton described as “injustices” by FBI agents in the Bureau’s Boston field office. Committee members prattled endlessly about the suspected misdeeds of agents — looking, of course, to surf a wave of popular sentiment and perpetuate the idea that the “evil” FBI had somehow gone far out of its way to frame a minor league hood more than 30 years earlier. At the time, Rico was 76 years old, in failing health and knew that at least one Oklahoma detective had a bull’s-eye on his back. Chairman Burton asked him if he wished to proceed and Rico responded, “My counsel advised me to take the Fifth Amendment until you people agree to give me immunity. I have decided that I have been in law enforcement for all those years and I’m interested in answering any and all questions.” Rico had been on the right side of things all his life.

Add to the mix a nice, but naïve, Oklahoma detective coupled with a driven Boston federal prosecutor, zealous, very skilled, but deluded in thinking that a great many FBI agents were corrupt. The prosecutor was prone to exploiting some parochial law enforcement jealousies and the detective predisposed to accepting rumors and unsubstantiated stories as truth. Neither seemed too interested in thoroughly testing the statements from these desperate killers that the investigators were unduly eager to hear.

Finally, the FBI, paralyzed by the corruption in its Boston Office, apparently feared to do anything that might be perceived as “covering up corruption” within its ranks. The Bureau owed Rico, a loyal and successful agent, an obligation to find out if he was guilty, or not, and it had a duty to bring the truth to light. At the time all this happened, he had been retired for more than 25 years and few in the FBI leadership knew Rico. The FBI protected itself and did not fulfill its obligation to its former agent.

Put all that together and our justice system, as good as it is, can and did go off the rails.

The result: An FBI agent who was one of the storied heroes in the Bureau’s war on Organized Crime was, at age 78 and ill, falsely charged with this 22-year old murder, held without bond and exposed to vicious beatings by inmates, then allowed to bleed to death, alone, shackled to a bed in a jail hospital in Tulsa, Oklahoma.

Paul Rico deserved much better.

–

Read More:

–

You must be logged in to post a comment.