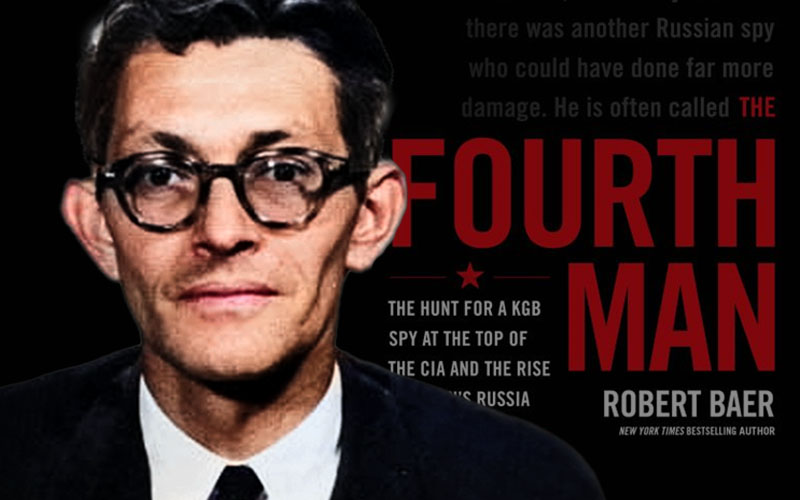

I wrote a book review in the summer of 2022 for the Fall 2022 issue of the Association of Former Intelligence Officer’s (AFIO) official publication, The Intelligencer: Journal of US Intelligence Studies. It was a review about The Fourth Man by Robert Baer:

The Ghost of Angleton — Review of The Fourth Man (pdf)

This year marks forty–eight years since William Colby fired James J. Angleton. A product of Yale University and Office of Strategic Services, the dark and brooding Angleton spent much of World War II in London learning the counterintelligence trade at the feet of British experts believed to be among the world’s best at this practice.

One important influence on him was Kim Philby, a close friend, head of counterintelligence for British Secret Intelligence Service (SIS), and a star of the notorious Cambridge Spy Ring that for years passed secrets to Moscow. In 1947, Angleton joined the newly-created Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). Seven years later, Allen Dulles appointed him head of counterintelligence where he remained until his ouster in August 1974.

Over those twenty years, his growing influence produced an Agency tied up in knots. First among his disasters was an unshakable belief in a so-called Monster Plot, a baseless Sino-Soviet strategic deception campaign cooked up in Moscow and Beijing to convince the West of an ideological rift between the two Marxist giants. Angleton also ordered all KGB and GRU officers offering to spy for the CIA turned away as Russian provocateurs if they disagreed with his thesis.

And finally, there was his religious belief, a groundless paranoia of sorts, that Moscow had penetrated the highest ranks of the CIA requiring him to conduct a series of “mole hunts” in an effort to unmask the traitor. During all this time, he managed to upend Agency operations, create an atmosphere of fear and distrust, and derail careers – all in an attempt to find a spy who never existed. In the end leaving America blind and deaf to Russian thinking at a most dangerous time in the Cold War.

It was with thoughts of the pall Angleton held over the Agency for so long that I recently (in June 2022) read The Fourth Man, a new book written by Robert Baer, published in May 2022 by Hatchette Books, an imprint of Perseus Books, LLC.

* * *

Baer weaves a complex tale of a possible KGB mole working at the senior levels of CIA’s ultra–secret Soviet Operations Division during the 1980s and 90s. Someone with knowledge of every important source the CIA and FBI were running against the Russians.

The story opens in 1992 on the streets of Moscow with the hunt for “Max,” nickname for Alexander Zoporozhsky, a First Chief Directorate counterintelligence officer with information vital to the CIA. For some time, Max had been a lackluster agent relegated to a backburner until the day he dropped the secret of an unauthorized meeting in Caracas, Venezuela between a CIA officer and another KGB officer. That little nugget led to the espionage arrest of Aldrich Ames, then head of CIA’s Soviet counterintelligence unit.

It wasn’t long before Max, now considered the Agency’s top KGB source, dropped a new bombshell – his service had another well-placed source at the highest levels of CIA. All Max knew was that he had provided unique documents pinpointing sites used by CIA officers to meet agents in Moscow. He had seen some of them. As if this was not chilling enough, the mystery man was also a regular at exclusive meetings attended only by CIA division chiefs.

So startling were Max’s revelations that the CIA launched an internal probe to find the mole. It would later become known to many in the closed world of American counterintelligence as the “Big Case” and later still as the hunt for “the Fourth Man.” The case would run for the next thirty years.

The author is no stranger to spying. Born in Los Angeles and raised in Colorado, Baer attended UCLA before completing a degree at the Georgetown School of Foreign Service and then joining CIA’s Clandestine Service as a case officer. Fluent in Arabic, Persian, Tajik, and Baluch, he spent most of his career running agents in the Middle East.

After twenty-one years with the Agency, he retired to write books. His best-known works See No Evil and Sleeping with the Devil were adapted into a screenplay which became the basis for “Syriana,” a movie starring George Clooney cast as a figure loosely based on Baer. Since then, he has hosted the History Channel series “Hunting Hitler” and later “JFK Declassified: Tracking Oswald.” He also contributes to Vanity Fair magazine and is a Middle East expert for CNN.

* * *

The timing of Max’s information could not have come at a worst moment for CIA. Few Langley leaders wanted to think about moles. Baer is harsh in his criticism calling them a “seraglio of eunuchs with their heads buried in the sand.” It was an abdication of responsibility, as he saw it, that allowed the KGB to bring the CIA to its knees and do major damage to American intelligence.

Prompting this sudden timidity was a new wind blowing through the office suites of Russia Division [SR Division]. Leading the wave was Milton Bearden. A career case officer with an outsized persona, Bearden had made his reputation as station chief in Islamabad, Pakistan rearming Afghan mujahideen guerrillas whose fighting skills later helped expel Soviet forces from Afghanistan.

As the Russian Division’s new chief, Bearden had a mandate to root out what many at CIA saw as an old guard of Cold Warriors still harboring an “unhealthy fixation on the KGB.” Viewing Russia’s intelligence services as a spent force in the new post-communist world, he ordered a series of sweeping reforms – chief among them – an end to recruitment of intelligence officers and turning away volunteers. (NOTE: Among the rejected was Vasili Mitrokhin, a KGB archivist who spirited out priceless intelligence.)

Bearden feared that if the Russians got a whiff that CIA was still pursuing them “they would take it amiss.” For the new boss, Baer writes, Russia was his “chasse gardée” – private hunting preserve. In the end, the author takes dead aim at Bearden for the havoc he wrought. “With his winding down of Russian operations in the early nineties, he’d done more damage to intelligence collection in Russia than anyone else other than Howard [Edward Lee Howard, a rookie case officer in the early eighties who volunteered to the KGB after the CIA fired him] or Ames.”

How then to account for Max’s fresh information? As no one wanted to contemplate the possibility of a high-level mole in the Russia Division, the party line was to conveniently hang all losses in the eighties on the shoulders of Ames and Howard.

Not everyone, however, was convinced of this theory. A careful flip through the records would have revealed compromised CIA and FBI sources unknown to Ames and Howard and later to the FBI’s, Robert Hanssen. Nor did they have access to Moscow site documents or ever attended a division chief meeting. One skeptic was Hugh “Ted” Price. As the CIA’s deputy director of operations, he questioned the Ames/Howard theory finding it a bit too convenient. Three months after Ames’s arrest in February 1994, Price quietly ordered the start of a counterintelligence investigation to examine the anomalies and inconsistencies. In doing so, he had no choice but to surround it with absolute secrecy.

The White House and Congress were demanding answers as to how a loser like Ames could slip through the security nets. As outrage grew, the FBI swept in to take over the Agency’s counterespionage duties. CIA workers were still reeling from Ames’s arrest three months earlier. Price feared that a leak of a new probe for a spy more senior than Ames could very well destroy the Agency. Baer lauds Price for his “courageous decision.”

Leading the inquiry was a veteran officer, Paul Redmond, Number Two Man in the counterintelligence unit. (NOTE: Price was adamant that Redmond’s boss, John Hall, and the Russia Division leadership remain in the dark.) He was a logical choice. Included in his impressive resume was oversight of operations in Moscow, heading Soviet Division counterintelligence and its Number Two Man, and having successfully led the investigation that identified Ames. Thus was born the Fourth Man investigation.

For the daily nitty-gritty work, Redmond chose Laine Bannerman, a veteran Russia analyst. She would head a four-person team, one that included James Milburn, a top FBI Russia specialist. Operating from a vaulted windowless room, the new Special Investigations Unit [SIU], as it was called, set about building a matrix that would hopefully lead them to the Fourth Man through a process of elimination.

The Price-imposed security regime produced an SIU investigation that was seriously handicapped from the start. Operating “under the radar” to avoid detection meant severely restricting what they could examine. Cable traffic queries to CIA stations and foreign liaison services, along with FBI records, for instance, were off-limits as were insights from defectors. Interviews of CIA employees were forbidden. Only CIA archives and files [NOTE: security files were off-limits as well.] could be checked in the hope of constructing “at most a faint and broken breadcrumb trail that may or may not lead spy catchers to a name.” Any suspect produced would be a matter of “inference and conjecture.”

But SIU did settle on a name. In a move reeking of questionable journalistic ethics, Baer publicly reveals Bannerman’s spy knowing that she and her SIU team had produced not a shred of solid evidence against the person. Mindful of the Brian Kelley tragedy, I am excluding the name from this review in the interest of fairness and justice.

In crafting his story, Baer left scholarship seriously wanting. Over two or three years of research and writing he has cast a very narrow net for sources. There were no primary sources of any kind, nor did he attempt to negotiate with the CIA for any records. As for the FBI, he sent one unresponsive email. Instead, the book relies heavily on secondary sources, in particular Milton Bearden’s Main Enemy and Circle of Treason, a look at CIA’s Ames investigation, by Sandy Grimes and Jean Vertefeuille. By my count he cites them nearly eighty time in his notes.

In the end, he is forced to concede that his efforts were largely “reportorial” in nature having spoken to sources, many anonymous – all “circumspect” in their remarks. Among those interviewed were some who believed the mole was real, others who thought he may have existed, while others were convinced there was no Fourth Man. Still others had never heard of the investigation including a number of unnamed CIA directors and James Clapper, a former Director of National Intelligence.

Whatever the truth, Baer admits that he has uncovered a mere “slice” of a much larger story; touting it as a “satisfactory composite picture of the Fourth Man investigation” – or at least the “inaugural stages of it.”

Baer has written a light read. Take it with a large grain of salt. Better yet, let’s wait for a disgruntled Russian to deliver the Fourth Man’s name. If he truly existed.

~

Dr. Batvinis is a historian and educator specializing in the discipline of counterintelligence as a function of statecraft. For twenty-five years (1972-1997) Dr. Batvinis was a Special Agent of the FBI concentrating on counterintelligence and counterterrorism matters. His assignments included the Washington Field Office and the Intelligence Division’s Training Unit at FBI headquarters. Later he served in the Baltimore Division as a Supervisory Special Agent where he supervised the espionage investigations of Ronald Pelton, John and Michael Walker, Thomas Dolce and Daniel Walter Richardson. Following 9/11, Dr. Batvinis returned to the FBI for three years managing a team of former FBI agents and CIA officers who taught the Basic Counterintelligence Course at the FBI Academy. In addition to authoring scholarly articles, he has contributed to the Oxford History of Intelligence, an anthology of essays, published in 2009 by Oxford University Press. He has produced two books on the history of the FBI’s counterintelligence program. The Origins of FBI Counterintelligence, (University Press of Kansas [UPK], 2007), and Hoover’s Secret War Against Axis Spies, (UPK, 2014). He is currently writing a biography of William Weisband, an early Cold War American spy, while completing the third of a three volume history of the FBI’s activities during World War II.

You must be logged in to post a comment.