I’m a big fan of the Antique Roadshow which appears regularly on my local PBS station in Washington. Its always enjoyable for me when someone brings in for an appraisal some old object that has been kicking around the house or has hidden in some attic for decades only to find that it is a priceless artifact worthy of care and attention.

This story and the backstory that accompanies it are literary versions of such a priceless Antique Roadshow discovery. To think that a young Harper Lee wrote this article when she was working as an obscure researcher helping her friend, Truman Capote, with his book; all the while hopefully awaiting the publication of her own book – one that would turn her into a legend.

It is equally interesting at this moment in time considering the new and revised stage version of Miss Lee’s classic novel To Kill a Mockingbird written by legendary Hollywood screenwriter, Aaron Sorkin, which is currently running at the Shubert Theater in New York. It stars Jeff Daniels as the iconic southern lawyer, Atticus Finch. I hope you enjoy it.

Exclusive: Read Harper Lee’s Profile of “In Cold Blood” Detective Al Dewey That Hasn’t Been Seen in More Than 50 Years (Smithsonian)

By

The murder of the Clutter family in rural Kansas captivated America when Truman Capote published his report in the New Yorker in 1965 and then in a full-length book soon after. Capote rose to fame as a renowned author and Kansas Bureau of Investigation agent Alvin Dewey became, in the words of the Wall Street Journal, “the most famous Kansas lawman since Wyatt Earp.”

But five years earlier, Capote’s dear friend and colleague Harper Lee wrote her own profile of Dewey, published in March, 1960, in the pages of the Grapevine, a membership magazine of the Society of Former Special Agents of the FBI of which I am the editor. Lee was just months away from becoming famous in her own right; To Kill a Mockingbird would hit bookshelves in July of that year.

Lee’s unattributed article was unknown to historians until recently. Her biographer Charles Shields contacted us because in his research he had learned that the Grapevine may have an article written by Lee. He sent a blurb from the February 19, 1960, Garden City Telegram, which read:

“The story of the work of the FBI in general and KBI Agent Al Dewey in particular on the Clutter murders will appear in ‘Grapevine,’ the FBI’s publication. Nelle Harper Lee, young writer who came to Garden City with Truman Capote to gather material for a New Yorker magazine article on the Clutter case, wrote the piece for the ‘Grapevine.’ Miss Harper’s first novel is due for publication by Random House this spring and advance reports say it is bound to be a success.”

There had been rumors for years that Lee had published a piece in the Grapevine, but her omitted byline kept the story hidden until Shield’s tip revealed the month and year of its publication. The likely reason the piece had no byline, Shields hypothesizes, is that Lee did not want to take any attention away from her friend’s work. “Harper Lee was so protective of Truman, the Clutter case was his gig,” Shields told the Atlanta Journal-Constitution. “She didn’t want to steal from him.”

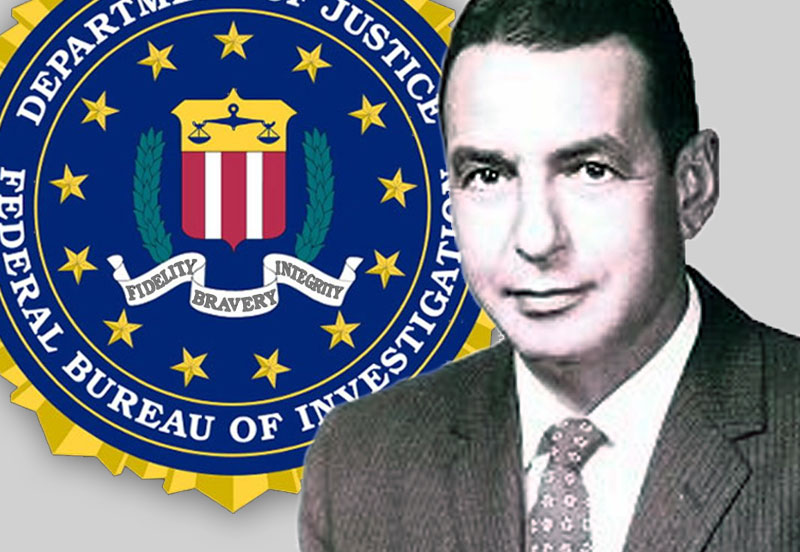

Dewey, the subject of her article, was a former FBI Agent and a member of the Society of Former Special Agents of the FBI, which would explain this story’s appearance in the Grapevine.

Below, for the first time ever, Lee’s article is being made available to the general public.

This article was republished with permission of the Society of Former Special Agents of the FBI.

**********

Dewey Had Important Part in Solving Brutal Murders

Resident Agent for Kansas Bureau of Investigation Helped Bring to Justice Killers of His Neighbors

Former FBI Special Agent (1940-1945) Alvin A. Dewey Jr., and his colleagues in the Kansas Bureau of Investigation recently put the finishing touches on the most extraordinary murder case in the history of the state.

Dewey, a resident KBI Agent located in Garden City, Kansas, was called into the case on November 15, when the bodies of Herbert Clutter, his wife Bonnie, and their teenage children, Nancy and Kenyon, were discovered in their home near Holcomb, Kansas. All were bound hand and foot and shot at close range with blasts from a .12 gauge shotgun. Clutter’s throat had been cut.

Clutter, a prominent wheat farmer and cattleman in Finney County, was a founder of the Kansas Wheat Growers Association. He was an Eisenhower appointee to the Federal Farm Credit Board, and at the time of his death he was chairman of the local farm cooperative. The Clutter family were prominent Methodists and leaders in community activities.

Drew Nationwide Attention

The case received nationwide coverage in newspapers and news magazines. Time, in its November 30 and January 18 issues, devoted several columns to the murders. Truman Capote, well-known novelist, playwright, and reporter was sent by the New Yorker to do a three-part piece of reportage on the crime, which will later be published in book form by Random House. Capote is the author of The Grass Harp, The Muses are Heard and Breakfast at Tiffany’s.

At a Loss For Motive

At first, KBI investigators were at a loss to find a motive for the senseless, brutal slayings. Although Clutter’s farm operations were extensive, and his office was in his house, he was noted for never carrying large sums of money on his person nor transacting business in any other way than by check. The Clutter family were popular members of the Holcomb community and near-by Garden City. None of them had an enemy in the world.

Dewey Personal Friend

Dewey’s role as field supervisor of the KBI investigation was doubly hard; the late Herbert Clutter was a close personal friend. Asked if he would pursue the case to its conclusion, Dewey said, “I’ll make a career of it if I have to.”

The clues Dewey and his colleagues worked on in the beginning were meager. The killers took with them the gun and shells used to murder the family; adhesive tape used to gag three of the victims could have been bought anywhere. The nylon cord with which the family were bound was of a common variety. Fingerprints were out of the question; when the house was carefully gone over, the results were prints of scores of Clutter’s friends. The house, according to one friend, “. . . was like a railway station.”

Footprint Discovered

However, in the basement furnace room where Clutter’s body was found, investigators discovered a clear footprint etched in blood. In the dust on the floor, picked up by a powerful camera, were more footprints. A portable radio was missing from Kenyon Clutter’s room and the family’s pocketbooks and billfolds had been ransacked.

As none of the family was sexually molested, Dewey was confronted with three possibilities: the crime could have been the random work of a psychotic; robbery could have been the motive; or persons with a grudge amounting to murderous intent against any of the family could have been responsible, stripping the house of cash and small items to make robbery seem the motive. Each possibility was improbable.

Checked out 700 Clues

The KBI checked out over 700 pieces of information, and Dewey himself conducted 205 interviews in the intensive search for the killers. Everything led nowhere. But in early December, a strange bit of information was given to the KBI. It sounded fantastic, but the KBI was sensitive to any and all possible leads. A former employee of Herbert Clutter told a bizarre story of the projected robbery of a safe in the home of a prominent Kansas farm family. There was no such safe in the Clutter home, but at least there was a motive.

Dewey and his associates went into action. They discovered no alibi for the suspects from noon, November 14, to noon the next day. In Kansas City, warrants were out for the pair on bad check charges. Both suspects had criminal records and had served together in Lansing penitentiary, but neither had records for crimes of violence. The KBI turned up a .12 gauge shotgun and a hunting knife in the home of one of the suspects. On December 15, a KBI agent flew to Las Vegas and points west with “mug shots” of the pair and advised authorities that the suspects should be picked up on parole violation charges.

Nabbed December 30

The KBI watched and waited. On December 30, as he was having dinner in his home, Al Dewey received a telephone call saying that the two had been picked up in Las Vegas only 30 minutes after their arrival. Dewey, with other KBI agents, left early next morning for Las Vegas.

On Sunday, January 3, Richard Eugene Hickock, 28, confessed his part in the slaying of the Clutter family. One day later, Perry Edward Smith, 31, gave an oral confession to the agents. The pair were returned to Finney County jail, Garden City, where they were formally charged and await trail, each on four separate counts of first degree murder. Their activities in Holcomb netted them between $40 and $50 in cash.

Wife Was Bureau Secretary

Al Dewey, 12 pounds lighter from his exertions, looks forward to settling down again with his family at 602 North First Street in Garden City. Dewey’s family consists of his wife, the former Marie Louise Bellocq, who was a secretary in the New Orleans FBI office, their sons, Alvin Dewey III, 13, and Paul David Dewey, 9, plus Courthouse Pete, the family watch-cat. Pete, age 4, weighs 13 pounds is tiger-striped and eats Cheerios for breakfast.

Dewey was born September 10, 1912 in Kingman County, Kansas. His family moved to Garden City, in 1931, and Dewey continued his education in the local high school and junior college. He attended California State in San Jose, where he played basketball and majored in police administration. He served with the Garden City police department three years, was with the state highway patrol two years, and joined the FBI in 1940. While with the Bureau he served in New Orleans, San Antonio, Miami, Denver, and the West Coast.

Was Sheriff 10 Years

After the war he returned to Garden City, and in 1947 was elected sheriff of Finney County, an office he held for 10 years until he joined the Kansas Bureau of Investigation. Dewey’s territory with the KBI includes southwest Kansas, but he is subject to call anywhere in the state.

Dewey owns a 240-acre farm near Garden City, which he rents and uses for pheasant hunting, but during the Clutter case he ” . . . only went by there a couple of times.” He is president of his Sunday School class at the First Methodist Church, of which Herbert and Bonnie Clutter were members.

Dewey thinks he will have a hard time settling down again to routine larceny and burglary cases, but he feels an abiding sense of personal satisfaction in having brought to justice the killers of his friends in Holcomb.

You must be logged in to post a comment.