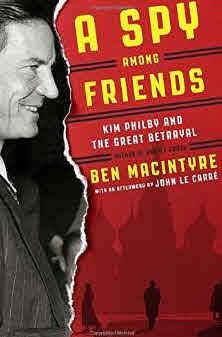

My review of “A Spy Among Friends: Kim Philby and the Great Betrayal

My review of “A Spy Among Friends: Kim Philby and the Great Betrayal” by Ben Macintyre

British author and columnist Ben Macintyre first burst on to the American scene in 2007 with “Agent Zigzag: A True Story of Nazi Espionage, Love, and Betrayal,” the story of British crook and con-man Eddie Chapman who became one of MI5’s most accomplished Second World War double agents.

Macintyre followed this success with two more wartime tales. “Operation Mincemeat: How a Dead Man and a Bizarre Plan Fooled the Nazis and Assured an Allied Victory” is the story of Major Martin, an imaginary British army officer whose corpse washed up on the Spanish coastline carrying carefully fabricated documents designed to deceive the Nazis about Allied moves in the Mediterranean.

Next came Double Cross: The True Story of the D-Day Spies a recounting of MI5’s stable of double agents (both real and fictional) who brilliantly misled the Germans concerning the date and location of the Normandy Invasion.

“A Spy Among Friends: Kim Philby and the Great Betrayal” is Macintyre’s latest offering. Staying with the British espionage genre he turns this time to Russian spying starting before the Second World War and moving into the Cold War. Through the prism of a “particular sort of friendship that played an important role in history” the author hopes to achieve a new understanding of the “most remarkable spy of modern times.”

This is actually a dual biography combining the oft told story of Kim Philby, the notorious traitor who burrowed his way into the Secret Intelligence Service (SIS) for nearly twenty-five years together with a lesser known, but far more interesting, look at Philby’s closest friend and fellow SIS officer, Nicholas Elliott.

The “very British” relationship between these two men flowered in traditional fashion. Both came from well-established upper-class families devoted to Empire and dominated by icy-cold, demanding yet distant fathers.

Kim and Nick were public school trained first at Eton and then on to Cambridge University where life-long friendships were forged with gentlemen of similar ilk.

The right London club was also essential for advancement –Elliott belonged to Whites – the Athenaeum claimed Philby. As Britain slipped ever closer to war, the twenty four year old Elliott (eager for adventure) and Philby (eager for more secrets) became instant friends when both joined the SIS.

For Elliott there was an element of hero worship in the relationship. Philby, who exuded competence, confidence and worldliness, seemed so much older (he was twenty eight) and mature. Elliott revered him as a heroic “louche’ who had barely escaped death during the Spanish Civil War.

How then did Kim really view Nick? Macintyre offers his readers a wry hint noting that in Philby’s strangely schizophrenic world, “the demands of revolutionary orthodoxy” always trumped family and friendships.

Macintyre slides his narrative back and forth tracing the arc of each man’s personal and professional life as SIS officers through the turbulent forties and fifties.

The usual suspects also make their appearance. Among others there is FBI director J. Edgar Hoover and Bill Harvey, the former FBI agent turned CIA counterintelligence officer, who were convinced of Philby’s perfidy. Then there was James Angleton, the legendary CIA counterintelligence guru who was totally bamboozled by his treacherous friend and mentor.

As a consequence of the uproar following the 1950 defections to Russia of Donald Maclean and Guy Burgess, suspicion immediately fell on Philby leading to his ouster from SIS. The already strained relations between MI5 and SIS suddenly exploded into a ferocious decades-long struggle with MI5 convinced of his guilt.

Led by the ever-faithful Elliott, SIS closed ranks around him. Macintyre ends the story in 1963 with Elliott in Beirut unmasking (partially) Philby in a bizarre confrontation that left this reader scratching his head.

Agent Zigzag and Operation Mincemeat benefited greatly from newly discovered original sources. No such claims can be made for this work. In fairness, Macintyre acknowledges at the outset that until CIA, MI6 and KGB files are released a full and complete understanding of Philby’s treachery is impossible.

Nevertheless, Macintyre has cobbled together a very readable narrative, but one that relies heavily on well-worn secondary sources. (Philby’s My Silent War: The Autobiography of a Spy, Knightley’s The Master Spy: The Story of Kim Philby

, Genrikh Borovik’s The Philby Files: The Secret Life of Master Spy Kim Philby

as well as Elliott’s own memoirs Never Judge a Man by His Umbrella

and With My Little Eye: Observations Along the Way

, both written in the early nineties.)

Is Philby the “most remarkable spy” in modern times as Macintyre claims? For a British audience – maybe. Americans, however, who have experienced decades of treachery from the Rosenbergs to the Walker family to Bob Hanssen to Anna Montes may have a very different view.

This is a good read but no “new understandings” here.

You must be logged in to post a comment.