“What was she thinking”? That was a question posed by former FBI director James Comey in his 2018 memoir, A Higher Loyalty. It refers to his bewilderment over former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton’s decision to set up an unsecure email server in the basement of her New York home to conduct American foreign policy in violation of State Department regulations while serving in the Obama Administration.

A year later that is the same question many Americans are asking themselves about Comey’s thought processes.

For a few years I had the pleasure of being in the company of Jim Comey who was unceremoniously dismissed from his position by President Trump on May 9, 2017. Those few occasions at FBI headquarters were meetings involving the FBI’s liaison with the Society of Former Special Agents of the FBI through a committee of which I was a member at the time.

The tall, lanky New Jersey native was very different from his predecessor, Bob Mueller, who in the times I met him struck me as distant, guarded, buttoned – up, aloof. By contrast Comey always walked into our meetings with a big grin eager to shake everyone’s hand before removing his suit jacket and sitting down at the head of the table.

Here was a professional steeped in the world of federal law enforcement. After completing his law degree at the University of Chicago Law School in 1985 Comey joined the office of the U.S. Attorney for the Southern District of New York, where he rose to Deputy Chief of the Criminal Division. For five years he was the Managing Assistant U.S. Attorney in charge of the Richmond Division of the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the Eastern District of Virginia before returning to New York in January 2002 as the U.S. Attorney for the Southern District of New York. A year later he came to Washington with an appointment as Deputy Attorney General for the Department of Justice. He even served briefly as Acting Attorney General when his boss, John Ashcroft, was incapacitated in a Washington DC hospital. For eight years he worked in the private sector before President Obama nominated him in 2013 to serve as FBI Director.

From what I understand Comey’s openness and easy-going personality made him a lot of friends and inspired considerable loyalty among the FBI workforce. In truth, I liked the guy even though we didn’t know each other.

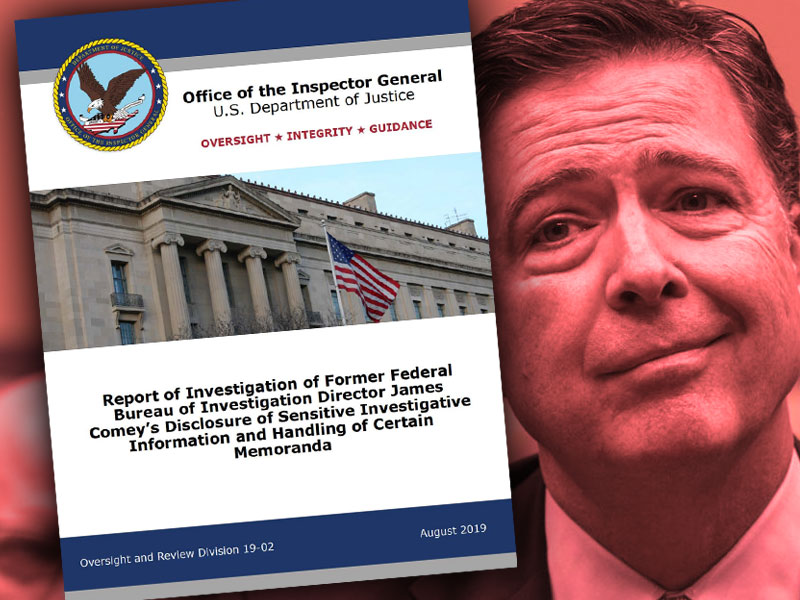

That’s why reading the Report of Investigation of Former Federal Bureau of Investigation Director James Comey’s Disclosure of Sensitive Investigative Information and Handling of Certain Memoranda was painful for me.

The report, authored by the Inspector General (IG) of the Department of Justice, Michael Horowitz, examines the circumstances of Comey’s creation and handling of nine memorandums while he was FBI director; seven dealing with his meetings with President Trump, his then chief of staff Reince Preibus and, Michael Flynn, the national security advisor. Another two memorialized telephone conversations with the president.

What is patently clear is that Comey was not a private citizen when these memos were created making them the exclusive property of the FBI. In fact, when asked later by IG investigators whether the president’s January 27, 2017 White House dinner invitation had been extended because of Comey’s position as FBI Director or because of a personal relationship with Trump, Comey conceded that the two men “did not have a personal relationship” and that if he had not been the FBI Director, he would not have been invited to dinner by the president.

What Michael Horowitz rightly criticized was Comey’s callous disregard for the long – established FBI and Department of Justice rules and guidelines concerning the making and handling of government documents.

First, by failing to classify two memos later determined to be “Secret” and the other “Confidential.” He prepared some of them on his unsecure personal laptop or handheld mobile device; he retained four original memos in a personal safe at his home and then provided them and, in other cases, their contents to individuals who had no right to view them. Later, following his dismissal, he failed to return the memos stored in his safe to the FBI.

But most inexplicable and disturbing was his unauthorized disclosure of memos, one of which, was to a friend which became the center piece of a New York Times article published on May 11, 2017 (Two days after Comey’s dismissal) headlined “In a Private Dinner Trump Demands Loyalty. Comey Demurred”.

Three days later, again without authorization, Comey sent scanned copies of three memos in their entirety and a fourth redacted one from his personal email account to the personal email account of one of his attorneys, Patrick Fitzgerald. On May 17, Horowitz found, Fitzgerald forwarded the memos to Comey’s other attorneys, David Kelley and Daniel Richman, a Columbia Law School professor, former special employee of the FBI and Comey friend.

On May 16, 2017 Comey sent a digital photograph of a memo (describing Comey’s February 8, 2017 White House meeting with Trump during which the president allegedly asked Comey to drop an investigation of Flynn) to Richman via text message from his personal phone asking Richman to share the contents, but not the memo itself, with a specific New York Times reporter. That same day the Times published an article headlined “Comey Memo Says Trump Asked Him to End Flynn Investigation.” The following day Deputy Attorney General Rod Rosenstein authorized the establishment of a Special Counsel to examine the matter naming Robert Mueller to head the probe.

In A Higher Loyalty, Comey is spare with both the truth and the facts. He claimed that he had kept only one memo at his home viewing it as his “personal property, like a diary.” He told readers that “having accurate recollections of conversations with this (italics added) president might be important someday, which, sadly turned out to be true.” (244) Yet there is no mention of the other memos that he kept in his home safe, nor how they were created or his disregard for proper classification. As for the memo he slipped to Richman about the Flynn discussion, Comey, in a stunning feat of legal legerdemain, excused his action by claiming that the memo contained no classified information then adding that “a private citizen may legally share unclassified details of a conversation with the president and the press, or include that information in a book.” (270)

Horowitz was absolutely correct in assessing Comey’s unconscionable behavior as a failure to “live up to his responsibility” adding that by “not safeguarding sensitive information obtained during the course of his FBI employment, and by using it to create public pressure for official action, Comey set a dangerous example for the over 35,000 current FBI employees—and the many thousands more former FBI employees—who similarly have access to or knowledge of non-public information.” OIG Rpt., 60.

After reading the IG report one can only ask: “What Was He Thinking?”

Attached is a link to the full IG report so you can make your own assessment:

You must be logged in to post a comment.