Kudos to David Ignatius for writing this column in the Washington Post. Baer should be rightly mortified being called out by such a journalistic heavy weight. Goes a long way to restoring Paul’s honor.

By David Ignatius

Columnist, Washington Post, Feb. 16, 2023

Every good spy thriller needs a “mole hunt” — a search for the foreign agent who has burrowed his way to the heart of the CIA or MI6 and is stealing secrets faster than you can say John le Carré.

The “mole hunt” trope is so familiar in fiction that it’s easy to forget that, in real life, counterintelligence investigations are incredibly destructive. They ruin the lives of innocent people and leave behind stacks of questions that might be disputed for decades.

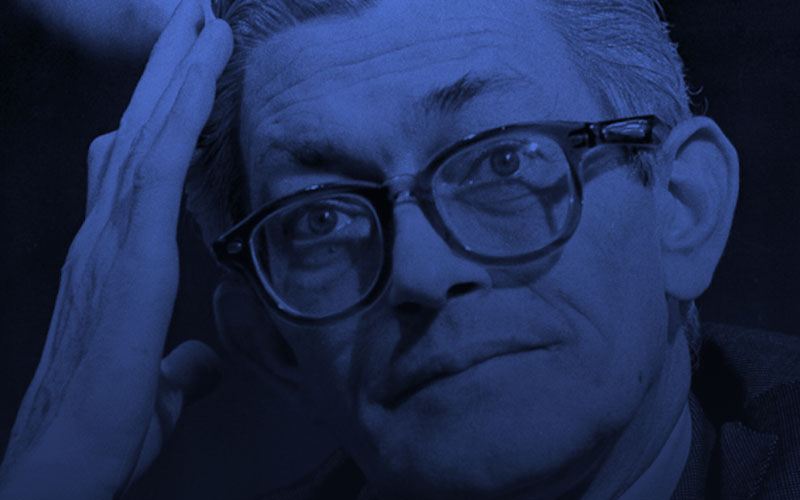

The latest example of mole-mania is the flap surrounding a book published last year by Robert Baer, a former CIA officer, titled “The Fourth Man.” Baer recounts unsubstantiated allegations by former CIA and FBI sources that Paul Redmond, who helped run CIA counterintelligence in the 1990s, was a “fourth” Russian spy who gave the Russians secrets beyond what they learned from traitors Edward Lee Howard, Aldrich Ames and Robert Hanssen.

Redmond and former CIA colleagues have convincingly rebutted the allegations The details are contained in a Feb. 5 article in the Cipher Brief by three former top agency officers, Michael Sulick, Lucinda Webb and Mark Kelton, and in a Feb. 6 “review” of Baer’s book by Redmond himself in the International Journal of Intelligence and Counterintelligence.

This flurry of commentary from CIA retirees is unusual. Gossips spins nonstop within this inbred group, but usually former officers keep it zipped in public, with their version of the aristocratic credo “Never complain, never explain.” Not this time.

“Robert Baer’s book is hogwash, filled with mistakes and misinformation. I have never ever been a Russian spy,” Redmond told the Law & Crime Network’s Brian Ross. Even Baer concedes in the book, “I don’t know who the Fourth Man was.” He told Ross: “If I were on a jury, I wouldn’t convict.”

Redmond, in his review, asks the obvious question in repudiating the charge: “If I were a spy, would I have … ?” Then he lists a series of well-documented actions he took against the Russians, including exposing Ames in 1991, creating a new CIA unit to look for other Russian penetrations beyond Ames, pushing for robust counterintelligence — in short, doing the opposite of what a Russian penetration agent would have done. Redmond retired from the CIA in 1997.

This story is interesting to me not for its particulars (I know both Baer and Redmond, and I wish for both their sakes that this book had never been published) but for several larger points it raises about the spy business and life.

The first is that the counterintelligence mind-set is a kind of organized paranoia. It’s toxic to an organization, and for that reason, it needs to be kept under tight control. When unproven suspicions escape internal controls (as inevitably seems to happen), they can become the intelligence equivalent of a deadly virus. A similar “Fourth Man” obsession engulfed British intelligence in the 1980s and led to cruel and unfounded attacks on former officers.

I had an unusual opportunity to watch this paranoia in action as a young reporter in the late 1970s. I had just begun covering the CIA for the Wall Street Journal when, on a whim, I called the home phone number of James Jesus Angleton, the retired chief of CIA counterintelligence. To call him a “legendary” mole hunter doesn’t do justice to how notorious and bizarre his investigative methods were. Even hardened CIA officers seemed terrified of him and his theory of all-encompassing Russian manipulation, known as the “monster plot.”

Angleton and I began to have regular lunches at the Army and Navy Club on Farragut Square. The details you might have read about him — that he chain-smoked Virginia Slims, holding them between his thumb and forefinger; that he drank tall, fruity cocktails with paper umbrellas until he was looped; that he was an amateur orchid raiser and gemologist — are all true. My wife still wears the engagement ring he helped me pick out at his favorite jeweler.

I used to wonder why Angleton was talking to a kid reporter like me (I was then 29). But as the years passed, it became obvious: He wanted an audience, and I (unlike most of his former CIA colleagues) was eager to listen to his baroque theories about how the Soviets had contaminated the CIA. He urged me to chase one lead, a Russian emigre picture hanger in Alexandria, who assumed when I called on him that I was yet another FBI agent sent to track down Angleton’s unfounded claim that he was a false defector.

The larger point here is that with Angleton, an appropriate skepticism had jumped the tracks into an obsessive and paralyzing paranoia. Many in the CIA came to believe that Angleton was haunted by his failure to realize that his 1950s MI6 lunchtime pal, Harold “Kim” Philby, was a Soviet spy.

But Angleton took his skepticism to a mad level after a 1961 Russian defector named Anatoly Golitsyn convinced him that every other Soviet defector would be a fake. This paranoia became so extreme that the CIA largely stopped operating against Moscow during the mid-1960s.

That raises a second epistemological point about counterintelligence. You can’t “know” whether someone is a recruited agent unless that person confesses — or you get hard intelligence that confirms his recruitment. That’s how Hanssen, the devastatingly effective mole in the FBI, was finally identified. U.S. intelligence recruited a Russian who could get into the Moscow files and lift his fingerprints.

Which brings me to a final larger point. In intelligence operations, as in life, we have to make decisions in the face of radical uncertainty.

I once asked former CIA director Richard Helms what he had made of Angleton’s case that the Soviets had poisoned every operation. Helms answered that the conspiracy theories were so convoluted that he couldn’t follow them. Helms decided that going further down Angleton’s rabbit hole was useless. He ordered the paralyzed division handling the Soviets to get back to work spying in the late 1960s, with a version of his characteristic admonition “Let’s get on with it.”

In the current case of over-the-top paranoia, Redmond’s defenders argue that the CIA should drop its usual, coy refusal to comment and say, flat out, that the evidence indicates that Redmond is innocent — and prevent future publication of “slanderous allegations.”

Screenwriters love a spy world painted in shades of gray. And the CIA often abets this ambiguity by refusing to comment on sensitive matters. But when something is clear-cut, as seems to be the case with Redmond’s innocence, the CIA should say so.

You must be logged in to post a comment.