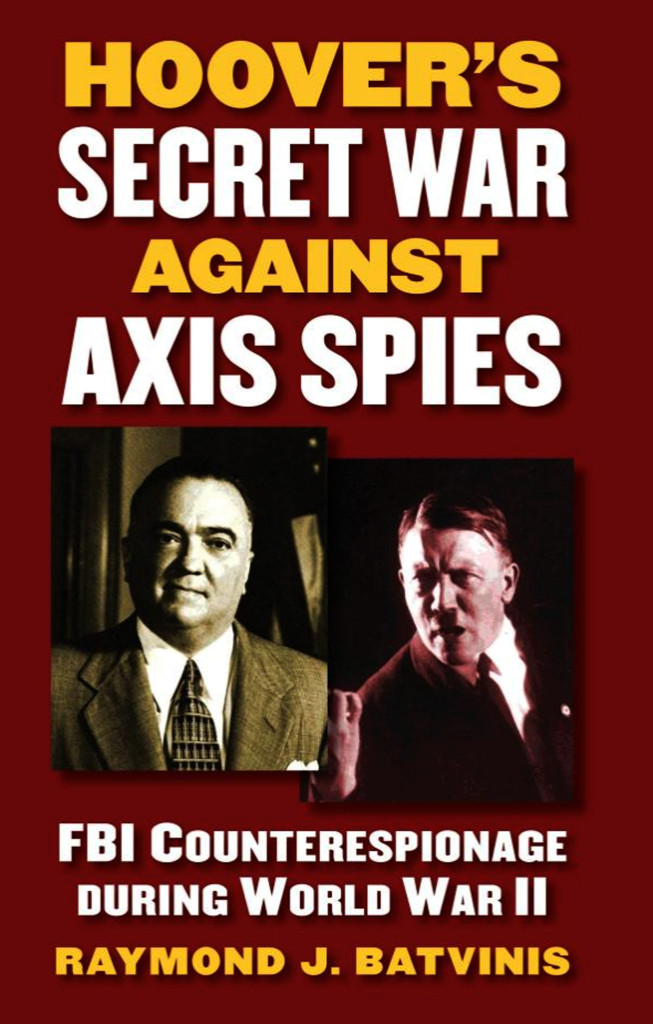

Rhodri Jeffreys-Jones reviewed my book, Hoover’s Secret War Against Axis Spies, in the summer 2016 issue of The Historian. published by the Phi Alpha Theta National History Honor Society. The Historian is a distinguished quarterly journal discussing interests in all fields of History and is highly regarded for its extensive Book Review Section.

Rhodri Jeffreys-Jones reviewed my book, Hoover’s Secret War Against Axis Spies, in the summer 2016 issue of The Historian. published by the Phi Alpha Theta National History Honor Society. The Historian is a distinguished quarterly journal discussing interests in all fields of History and is highly regarded for its extensive Book Review Section.

–

Numerous books on the history of United States espionage have followed an interpretation inspired by official historians of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). According to this school, America acquired a high degree of competence in World War II because of British tuition and guidance, much of it channeled through William Donovan (director of the wartime Office of Strategic Services, or OSS) via the United Kingdom’s New York-based spy chief William Stephenson. The viewpoint here is that the OSS was the blueprint for the CIA, and that the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) and its director, J. Edgar Hoover, played only a marginal role and sometimes threatened to be an irritant to the smooth functioning of US intelligence.

In the book under review, former FBI Special Agent Raymond J. Batvinis offers a different perspective. He points out that by 1943, Hoover “sat the top of America’s only civilian espionage service.” (106). Though the FBI director lacked knowledge or curiosity about foreign countries, which he never visited, he “built a formidable foreign espionage service” that was the true building block for the CIA’s Cold War clandestine capabilities (269). Batvinis acknowledges the British input but accuses Stephenson of “political ineptitude” in aligning himself with Donovan against Hoover, a miscalculation that weakened Cold War counterintelligence and allowed the Cambridge spy ring a protracted lease of life (270). For Batvinis, it was Hoover who played a “magnificent role” in the war (275).

Drawing on files held by the FBI, documents in the Franklin D. Roosevelt Library and the British and US archives, and privately held collections, as well as a variety of other sources, Batvinis opens his book with chapters on the development of the idea of central intelligence in the months before and after Pearl Harbor. Batvinis supplies new detail on the role of Hoover and other individuals, such as the State Department’s Adolf Berle, and highlights both the advantages of British help and the damaging friction that arose from it as jealous factions battled for supremacy.

The author continues by arguing that the FBI participated in crucial intelligence programs. One of these was Ultra, the British codebreaking effort against the German foe. The FBI’s Arthur Thurston went to London in November 1942 and received decrypts of interest to his bureau. Batvinis fails to distinguish, however, between Ultra and what Ultra produced–the FBI received only selected data, not the secrets of the codebreakers. In his discussion of the Double Cross system, too, Batvinis pushes his claims too far. The Bureau operated only on the fringes of this disinformation program. Similarly, he exaggerates when he says that the FBI operated outside its designated intelligence areas of the United States and Latin America. It had sent only fifty agents to Europe and Asia by 1947. In spite of all this, Hoover’s Secret War is a well-researched corrective to OSS-CIA-focused literature and would be a valuable addition to the shelves of the discriminating student of World War II’s intelligence history.

You must be logged in to post a comment.