This FBI history article appeared in the August 2017 issues of The Grapevine, published by the Society of Former Special Agents of the FBI. The article was written by by David H. Cutcomb (FBI 1968-1988).

Marsh Chapel Sanctuary Event (pdf)

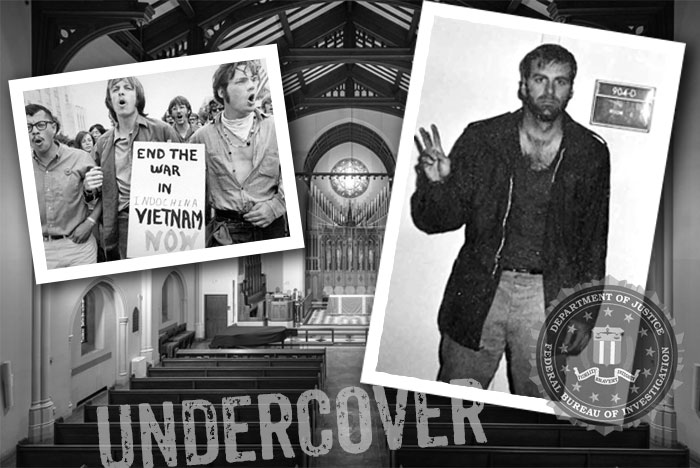

In 1968, as an FBI Agent assigned to the Boston Office and a Marine veteran of the Vietnam conflict, I was selected to go undercover at the Marsh Chapel on the Boston University campus, where students, et al, were harboring two military deserters — one a Marine (Thomas Pratt) and the other, a soldier (Raymond Kroll).

Boston was my first office, and at the time of this event, I had been there, assigned to Jack Kehoe’s Fugitive Squad, only a few months. To provide a typical example of my work during the six months I was on that Squad, I participated in apprehending 91 fugitives. Most of that work involved looking for fugitive violators wanted for felony-level crimes, including one from the Ten Most Wanted List. I also participated in apprehending a handful of military deserters. I mention all of that as background, and to put the nature of the workload in perspective.

While deserter cases were generally low priority and often routine, some of the most deadly encounters fugitive investigators have faced, were at the hands of military deserters. I encountered a couple of that ilk, later in my career. Working those cases, it became obvious that some deserters were senselessly willing to assault or kill to avoid capture.

At first glance, one would believe otherwise, considering the relatively light punishments that awaited deserters as compared to the penalties facing felony violators. I suppose a certain percentage of deserters were mentally unbalanced and found life, especially military life, traumatic, or beyond anything they could tolerate. Then too, being in a fugitive status naturally creates a potential for panic and thus, illogical and unpredictable behavior.

In this case, however, we never developed any indication that we might be dealing with irrational subjects, or their supporters. On the other hand, in any arrest situation, one should never say “never.”

A few years later, leading to the time of the “All Volunteer Army,” the military ceased looking for AWOL and deserter subjects. Instead, they began discharging them, thus relieving federal law enforcement from dealing with deserter cases.

The Bureau’s primary concern in this nationally publicized “Marsh Chapel Sanctuary” event was to evaluate what was involved before attempting any arrests, in order to avoid confrontations that might result in violence.

I was one of two Agents sent into the Chapel in an undercover capacity, tasked with contributing to the aforementioned evaluation. I was there, day and night for five days, until the last deserter (Private Kroll) was apprehended. I believe the other Agent, whose name I can’t recall and with whom I had only occasional contact, was actually one of two or three who rotated shifts.

For this assignment, I didn’t shave and dressed carelessly, wearing or carrying a Marine Corps utility jacket. I slept on, or under, one of the Chapel pews and generally just tried to fit in, with varying success. . . . . (read the rest)

You must be logged in to post a comment.