As you know November 11, 2018 marks the one hundredth anniversary of the Armistice that ended the First World War. As a reminder, today we call it ‘Veterans Day’ but for years a previous generation of Americans solemnly referred to it as ‘Armistice Day’ and wore a poppy on their lapels to remember those American GIs who gave their lives in that war. In Great Britain the poppy is still worn today as a token of remembrance for the millions of British soldiers lost in the trenches.

My good friend and colleague Dr. John Fox, the FBI’s historian, wrote an excellent article for the November 2018 edition of the Society of Former FBI Agents magazine, The Grapevine, on the wartime national security activities of the Bureau of Investigation (as the FBI was called then). I know you’ll find it interesting.

On the Homefront: The Bureau and National Security in World War I (pdf)

When war broke out in August 1914, the Bureau of Investigation was six years old and had only 161 full-time employees, 93 percent of whom were Agents.

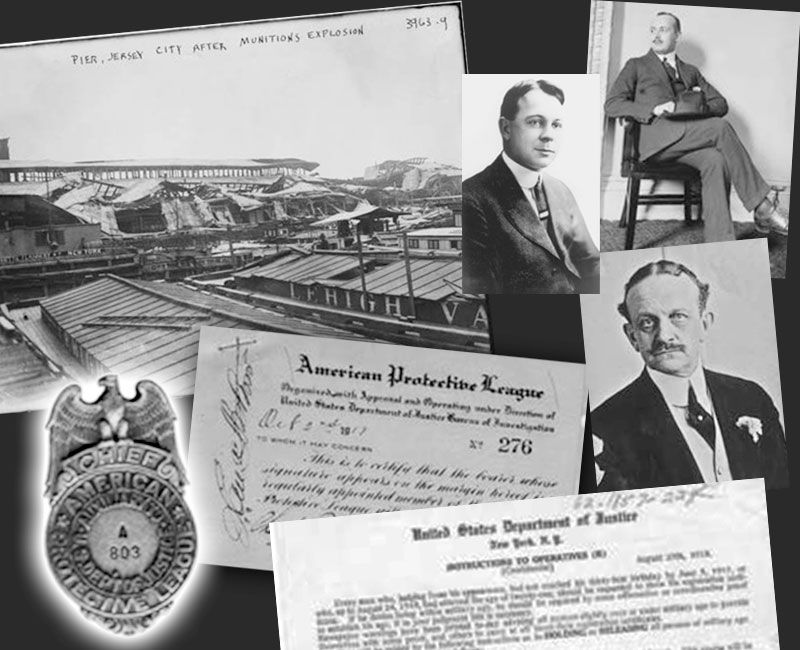

Bureau Chief Alexander Bielaski, a founding member of the Society, had been in charge for several years and was well adept at handling the Bureau’s main priorities – the interstate prostitution law, neutrality violations on the Mexican border, antitrust matters, bankruptcy fraud, and civil rights related matters. The National Security matters the Bureau dealt with largely related to stopping insurgents from using the American southwest as a staging ground for their the success of the recent Mexican revolution.

As the war progressed that fall, American neutrality came to be sorely tested. The United States found itself caught between the German and the British intelligence services as they covertly worked to woo the United States to their side, or at least keep the United States from joining with their enemy. In dealing with these threats, the United States began to educate leaders and its people about the threats these adversaries (and even future allies) posed. Such lessons would clearly inform our action in the next world war.

Germany’s problems were the most vexing. Unable to buy and ship U.S. war goods across the Atlantic due to the strength of the British Navy, Germany resorted to submarine warfare, sabotage, and subversion. German subs were hobbled as it was diplomatically untenable to target U.S. or other neutral ships.

Sabotage and subversion proved very successful as long as the attacks could not be linked back to Germany. Over the course of 1915 and 1916, many ships and tons of cargo were lost to unexplained fires and accidents by both U.S. and international ships. Sometimes ingenious chemical incendiaries were found in ship holds. Everyone suspected sabotage, but proof took time to develop.

There was a suspicious fire at the munitions transfer point at Black Tom Island in the New York Harbor, which led to an explosion that rocked the area with the force of thousands of tons of TNT. Several other munitions plants were also destroyed by mysterious fires.

Fragmented national security authority meant no organization had clear jurisdiction to investigate such events. The largest response to the unexplained fires and ship explosions came from the very capable, but jurisdictionally limited, New York Police Department’s Bomb Squad under Chief Thomas J. Tunney.

The U.S. Secret Service was also a significant respondent at first, and its agents helped to unravel a number of German schemes in the New York area.

One of their most famous exploits was when Secret Service Agent Frank Burke grabbed the attaché case of a suspected German agent. Burke and his partner had been following George Viereck, a German national; the Bureau would later arrest him under the Foreign Agents Registration Act during World War II. Under Burke’s eye, Viereck was joined on an elevated train to Harlem by a well-dressed older man. Burke realized it was Dr. Heinrich Albert, a German consular official who was suspected in a number of covert activities. When Viereck left the train, Albert became engrossed in his reading and almost missed his transfer. He rushed off the train, forgetting his case, and Burke grabbed it just as Albert turned back to get it. With no prosecutable evidence, the U.S. government leaked the contents of Albert’s briefcase to the press. The documents clearly showed German efforts to bribe union officials and to use local newspapers to promulgate German propaganda. The documents also hinted of other covert influence operations. . . . (read the rest)

You must be logged in to post a comment.