The following article I wrote was published in the Winter-Spring 2022 issue of The Intelligencer: Journal of U.S. Intelligence Studies.

__

The morning gloom was no match for the gnawing anxiety that gripped him, as he stepped the door of the American embassy at 1 Grosvenor Square.

Once a leafy park nestled in the heart of London’s swanky Mayfair district, Grosvenor Square had been dotted with benches lining paths used as short cuts and by casual strollers seeking some fresh air. Three and a half years of war had rendered it colorless with a combat ready appearance. Replacing the greenery were sandbagged bunkers abutting Quonset huts housing members of the Women’s Auxiliary Air Force (WAAF). The WAAFs worked for the British Balloon Command managing “ROMEO,” nickname for a huge barrage balloon, suspended hundreds of feet overhead on steel cables, designed to ensnare enemy dive bombers that dared to venture near.

The surrounding neighborhood was equally grim. Next to the embassy stood the derelict remains of the ambassador’s residence. A lucky bomb strike during the 1940 “blitz” had rendered it barely livable. Many of the nearby neo-Georgian buildings had suffered a worse fate.

Just days earlier he had been living in Washington, America’s capital, a city alive with energy, yet unscarred by war. Despite all the excitement around him, the last three years had been fairly routine. Every morning he trekked down Pennsylvania Avenue to a collection of office buildings called Federal Triangle. One of them housed the headquarters of the Department of Justice and the Federal Bureau of investigation. Following six years of cross-country action as a Special Agent, he had been ordered back to Washington by FBI director, J. Edgar Hoover. He was just another desk-bound bureaucrat; one of dozens managing spy cases around the country.

On this particular day, that humdrum world was an ocean away. Navigating his way through London, the nervousness only worsened as he drew closer to Whitehall, center of political and military power in Great Britain, and 10 Downing Street, official residence of Prime Minister Winston Churchill. His destination was “Broadway,” a collection of buildings near the Foreign Office.

In one of them waited a tiny group of anonymous mandarins—none of whom were particularly anxious to meet him.

***

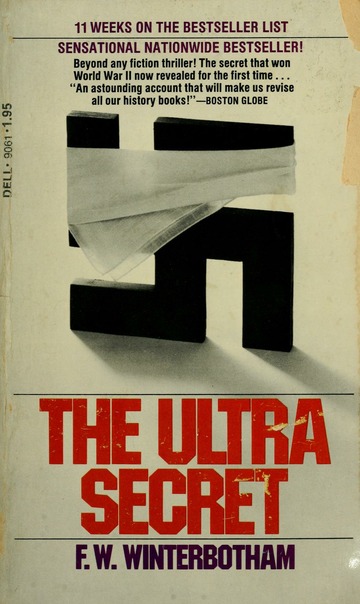

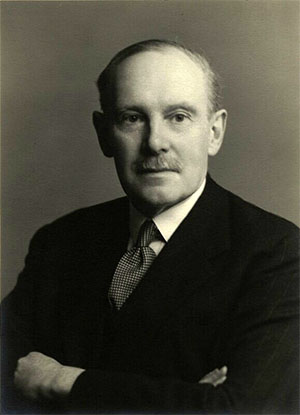

This strange saga would have remained classified, still buried deep inside British and American government vaults, but for the audacity and courage of one man. Frederick W. Winterbotham was an Englishman, born in 1897 in the market town of Stroud. As a subaltern and pilot with the Royal Flying Corp during World War I, he spent much of his time as a prisoner of war after being shot down over Belgium. While interned he studied German adding to his already fluent French. After earning a law degree at Oxford and a decade of civilian life, he returned to military service as an intelligence officer with the Royal Air Force (RAF).

At the start of the Second World War, Winterbotham, then a forty-two-year-old senior group captain with the RAF Intelligence Branch, was assigned to the British Secret Intelligence Service (Ml6). His assignment was to help manage the most important secret of the war after the atom bomb.

What Winterbotham dealt with was a miraculous codebreaking success that gave Allied commanders the “ability to read, at most of the important periods of the war, secret (communications) between the topmost enemy commands including Hitler himself.” He lauded its “unparalleled” strategic value for following the enemy’s thinking, plans, and intentions at the highest levels. Equally critical was its role in determining what the enemy did not know about allied intentions and operations. Churchill called it his “most secret source.” Dwight Eisenhower, the American army general destined to lead the invasion of Europe, spoke for all Allied commanders when he called it “priceless.”

What Winterbotham dealt with was a miraculous codebreaking success that gave Allied commanders the “ability to read, at most of the important periods of the war, secret (communications) between the topmost enemy commands including Hitler himself.” He lauded its “unparalleled” strategic value for following the enemy’s thinking, plans, and intentions at the highest levels. Equally critical was its role in determining what the enemy did not know about allied intentions and operations. Churchill called it his “most secret source.” Dwight Eisenhower, the American army general destined to lead the invasion of Europe, spoke for all Allied commanders when he called it “priceless.”

In April 1974, long retired from military service, Winterbotham published a memoir of his wartime experiences. Drawn largely from memory (he had no access to classified government files.), he revealed, for the first-time, details of the codebreaking success that contributed so much to winning the war. After three decades of government-imposed silence, the story of “Ultra,” top secret codename for this miracle source, became public. His book, The Ultra Secret, cracked open the door for the world to learn the true story behind the amazing victories against the Axis from North Africa, over the vast expanse of the Atlantic Ocean, and across the continent of Europe.

***

This now famous tale began in June 1938, more than a year before the start of the war in Europe. That month, the British government acquired Bletchley Park, a handsome Tudor style mansion in the Buckinghamshire countryside tucked away on a private estate about forty miles north of London. The purchase had a certain logic to it. Heavy Luftwaffe bombing of London was anticipated and the market town of Bletchley Park, near the estate, was safely out of harm’s way. It sat on an important communications link with London as well. Running through it was a railway line between Oxford and Cambridge University with direct connections to London. It was mainly these two titans of British intellectual firepower that provided the physicists, mathematicians, anthropologists, Egyptologists, along with German linguists and others required to do the job. Bletchley Park or “BP” (Station X to those really in the know) would serve as Britain’s nerve center for breaking Axis codes of all types throughout the war. What began as a modest effort in June 1939 with a staff of a hundred or so eventually ballooned to more than nine thousand men and women processing Hitler’s secrets on an industrial scale.

***

The German encipherment system used for its highest-level communications was called “Enigma;” from an ancient Greek word meaning puzzle. Originally designed in the 1920s by a German firm for confidential railroad and bank communications; it was soon adopted by the Wehrmacht for both the strength of its security and portability on the battlefield. During the war nearly ninety thousand Enigma machines were distributed to the armed forces and government ministries.

The device consisted of a sturdy wooden box that opened at the top revealing a set of typewriter keys and twenty-six lamps. Arrayed underneath the keyboard was a series of twenty plugs, a board with twenty-six ports, one for each letter of the alphabet, and three mechanical rotors, all connected by a series of wires. The operator, using a special key drawn from sheets distributed monthly, adjusted the rotors to the correct setting before typing the clear message. What emerged were gibberish letters that were then transmitted over the air. Another operator at the receiving end, relying on the same distributed key, typed in the letters causing the clear message to light up the lamps on his machine. The Germans, completely confident that the system was impregnable, never wavered in this belief right up to the end of the war. They had absolute confidence that an enemy could never run through the nearly 103 sextillion possibilities the Enigma machine generated to solve even one message.

Before the war, the Government Code and Cipher School (GC&CS), Britain’s codebreaking organization, knew little about Enigma. During the 1930s it had studied it off and on but, in the end, abandoned efforts in the belief that Enigma’s security could not be broken.

In July 1939, just weeks before the start of World War II, Polish intelligence leaders disabused British and French cryptologists of this notion at an emergency meeting with their Polish counterparts. What they revealed was breathtaking beyond belief. In a deeply wooded military camp on the outskirts of Warsaw, the guests learned that the Poles had been studying the Enigma problem throughout the 1930s and wished to share their findings. The puzzled visitors learned that three young mathematicians from Poznan, using only pencils and paper, had solved Enigma’s internal wiring system having never laid eyes on the machine. They also created an Enigma clone based on vague intelligence about what it looked like. It was this crude device that they unveiled for their astonished visitors. They also shared messages decoded on a sporadic basis. Lacking the finances and engineering capacity to build needed equipment to go further, and with war just weeks away, the Poles decided to turn their findings over to their allies. Stunned by this incredible news, the visitors took immediate steps to spirit the three mathematicians and all their research materials to Paris.

Armed with the Polish discovery, Bletchley Park undertook a second look at Enigma and quickly discovered critical weaknesses that the Nazis bad overlooked.

***

German cipher clerks were required to follow strict protocols when setting up their machine for daily operation. While most complied, some were sloppy and lackadaisical. Others facing chaotic battlefield distractions often rushed the procedures missing critical steps along the way. Bletchley Park instructed the British Y Service, scanning the airwaves for messages, to concentrate on certain operators flagged as weak links in the Enigma security chain. GC&CS jokingly labeled these back-door opportunities “cribs” or “cillies.” For the Germans, however, these mistakes were no joke. Cracking the puzzle of just one operator and one machine offered codebreakers entree to the entire Enigma system—for one day.

As useful as this hit or miss approach to communications intelligence was it soon proved inadequate for modern warfare. Unlike the First World War when static battle fronts shifted only a matter of miles over four years, the new war would be different. The Wehrmacht’s lightning strikes in 1939 and 1940 that crushed Poland and France in a matter of weeks had demonstrated that speed, maneuverability, and close air and ground force coordination would define the clashes to come. The stark reality of a constantly evolving battlefield meant that Allied strategists had to respond quickly with well-informed decisions about rapid troop and weapons movements on a grand scale.

Such judgments were only possible by following the progress of the war through the enemy’s eyes, having advanced knowledge of his next step; something that could only come from a constant stream of accurate communications intelligence. Cribs and cillies would not be enough. A faster, more reliable method of codebreaking had to be developed.

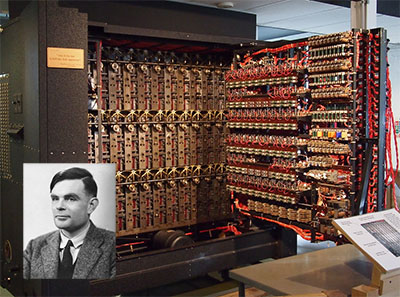

The answer came early in the war with the arrival at Bletchley Park of a brilliant young Cambridge mathematician. Alan Turing, father of the modern computer, would in decades to come be canonized by history as one of the twentieth century’s greatest scientific intellects.

Pulling out all the stops, Turing successfully produced a machine called a “bombe.” Winterbotham remembered it lovingly as the “Bronze Goddess.” It was room-sized and clunky, loaded with strange mechanical parts, dozens of greasy wheels and gears, all connected by miles of wiring that produced constant breakdowns. For technicians struggling to keep it running twenty-four hours a day-the device was nightmarish. For Allied planners, however, these headaches were a tiny price to pay for a man-made miracle. One that could search through hundreds of millions of letter combinations for a correct daily key setting in a fraction of the time it would take the human mind.

As more and more Turing bombes came online and linked together, what would have taken years to solve now sank to a matter of hours. Gradually Enigma’s safeguards began melting away. What started in 1939 as joy over an occasional broken message gave way to a staggering 90,000 a month by the end of the war.

***

One of the first series of Enigma ciphers to tumble were those used by the Abwehr, Germany’s all-important military intelligence service. It supplied all three branches of the armed forces with counterintelligence, counter-sabotage and foreign intelligence from around the world. The commander was Wilhelm Franz Canaris, a navy admiral, fluent in six languages, and an intelligence officer since the First World War. The first break came around May 1940 when veteran codebreaker, Oliver Strachey, solved the Abwehr hand-cipher. This uncomplicated system, designed for spies operating under dangerous conditions, was mobile, easy to operate and conceal, attracting little attention if discovered. The solution, a vital first leap forward in reading even stronger Abwehr communications, was named “Illicit Signals Oliver Strachey” or ISOS, in Strachey’s honor. Next came Dillwyn Knox, a Cambridge classics scholar and papyrologist. “Dilly,” as colleagues called him, joined GC&CS at the start of the First World War. Early in World War II he led a team that broke an important Italian naval cipher that produced a stunning British victory over a large Italian fleet at the Battle of Cape Mata pan.

A year after Strachey’s success, Knox achieved immortality by solving the Abwehr’s Enigma machine cipher. Starting in 1941 Bletchley Park began reading messages sent between Canaris’s headquarters in Berlin and his many stations around the world. For the rest of war, Britain remained fully informed about Abwehr strengths and weaknesses, the identity of its agents, intelligence priorities and targets, what it knew about British moves and, most importantly, what it did not know. Knox’s achievement was dubbed “Illicit Signals Knox” or “ISK.” By the end of the war, Bletchley Park had disseminated more than three hundred thousand ISOS messages and another one hundred and forty thousand ISK decrypts including reports essential to the success of the Normandy landings in 1944.

***

J. Edgar Hoover’s access to ISOS and ISK had no reason, rhyme, or wartime logic to it. Looking back over a span of nearly eighty years one can only describe it as pure “serendipity.”

As war clouds gathered over Europe in the late 1930s, U.S. officials grew increasingly concerned about what we refer to today as “national security.” Damaging espionage cases across the country, had exposed grave weaknesses in the government’s ability to protect important military secrets.

So concerned had President Franklin Roosevelt become that in June 1939 he took bold action. That month he ordered his cabinet secretaries to report all allegations of espionage, sabotage, and propaganda to the FBI for review. With the stroke of a presidential pen, the FBI became a central “clearinghouse” for such matters and America’s principal counterespionage service.

Hoover wasted no time acting on his new authority. He immediately ordered all assistant directors and Special Agents in Charge to attend the FBI’s first counterespionage school in Washington. Next, he started the Legal Attache Program by assigning an FBI agent to the American embassy in Ottawa, Canada. After a hiatus of nearly twenty years, he resurrected the General Intelligence Division, soon renamed the National Defense Division. To safeguard military-industrial secrets, he started the Plant Protection Program, forerunner of today’s Industrial Security Program. Specially trained agents became fixtures in weapons factories across the country inspecting them from top to bottom. In a historic step forward, the FBI director created the forerunner of the today’s U.S. Intelligence Community. The Interdepartmental Intelligence Conference brought together the heads of the FBI, the Military Intelligence Division of the War Department, and Office of Naval Intelligence for regular meetings on matters of related interest.

Hoover wasted no time acting on his new authority. He immediately ordered all assistant directors and Special Agents in Charge to attend the FBI’s first counterespionage school in Washington. Next, he started the Legal Attache Program by assigning an FBI agent to the American embassy in Ottawa, Canada. After a hiatus of nearly twenty years, he resurrected the General Intelligence Division, soon renamed the National Defense Division. To safeguard military-industrial secrets, he started the Plant Protection Program, forerunner of today’s Industrial Security Program. Specially trained agents became fixtures in weapons factories across the country inspecting them from top to bottom. In a historic step forward, the FBI director created the forerunner of the today’s U.S. Intelligence Community. The Interdepartmental Intelligence Conference brought together the heads of the FBI, the Military Intelligence Division of the War Department, and Office of Naval Intelligence for regular meetings on matters of related interest.

July 1940 witnessed further advancements. At the insistence of the President, Hoover established the nation’s first foreign espionage service. A month later the top-secret Special Intelligence Service (SIS) began sending undercover agents, posing as businessmen, to Latin America in search of political, economic, and military secrets. An additional presidential order launched large-scale FBI wiretapping of embassies and consulates of Spain, Germany, Vichy France, Japan, Italy, Portugal, and the Soviet Union—all in search of foreign intelligence and counterespionage information.

Around this time, William Stephenson, a wealthy Canadian businessman approached Hoover. Stephenson represented Stewart Menzies, the head of MI6, who wished to expand his service’s presence in the United States. Hoover was eager to help and for a while the relationship proved fruitful for both sides. What had started so positively, however, steadily deteriorated into acrimony and suspicion over the next two years. For Hoover’s part, he had gotten fed up with Stephenson’s blocking FBI access to the British Security Service (MI5) with whom there was much to share.

Finally, in November 1942, without prior consultation, Hoover dispatched twenty-eight-year-old Special Agent Arthur Thurston to London as his direct representative to MI5 and MI6.

[See related article: A Thoroughly Competent Operator: Former FBI SA Arthur Thurston]

***

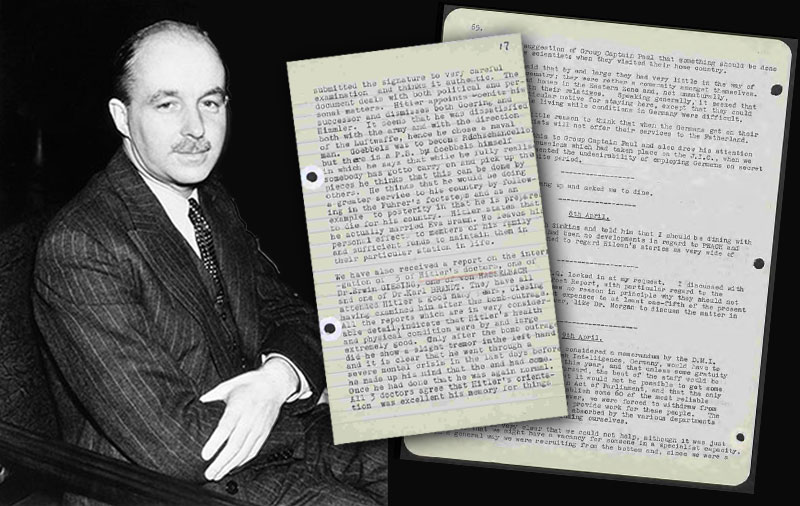

The first meeting between Thurston and Menzies, was a turning point for the FBI. Until then, Hoover had only the dimmest awareness that British codebreakers were reading Enigma messages. Perhaps most galling for him was being shut out over the past year from vital intelligence passing Berlin and spies in the Western Hemisphere.

The two men met at Menzies’s Broadway office on December 7, 1942, the first anniversary of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. After a few pleasantries, Hoover’s man weighed-in with the message that FBI relations with Stephenson’s office in New York were at an end. Menzies was undoubtedly stunned to hear that his personal representative in the United States had, in Thurston’s words, “damaged himself irreparably and would never be able to enjoy the Bureau’s confidence again.” Following that bombshell, Thurston shifted the conversation to Ultra. Hoover knew about the British success, and he wanted access to it. Thurston insisted that “any future cooperation” depended on it. He quickly offered assurances that his bosses were sensitive to Ultra’s importance to Allied victory and would comply with any security restrictions laid down by the MI6 director. How Menzies reacted to this news was never recorded, but within a month Thurston had been briefed on Ultra.

A visit was arranged for Thurston to the country home of Walter Grimston, Fourth Earl of Verulam in early January 1943. Nestled about twenty miles north of London near the ancient city of St Albans, the estate had been taken over by Section V, MI6’s counterespionage arm, for use in processing Abwehr decrypts sent from Bletchley Park. Escorting him that day was Menzies’s deputy, Valentine Vivian.

As the two men toured the facility, Thurston learned that no support assistance would be forthcoming to the FBI. The pressures of war had reduced available clerical personnel to a woeful few and those available were being gobbled up by the armed forces and government ministries. As for MI6, it was already stretched to the limit, barely keeping pace with the flow of incoming messages. Vivian pressed his guest to assign a fulltime FBI agent to review Western Hemisphere records.

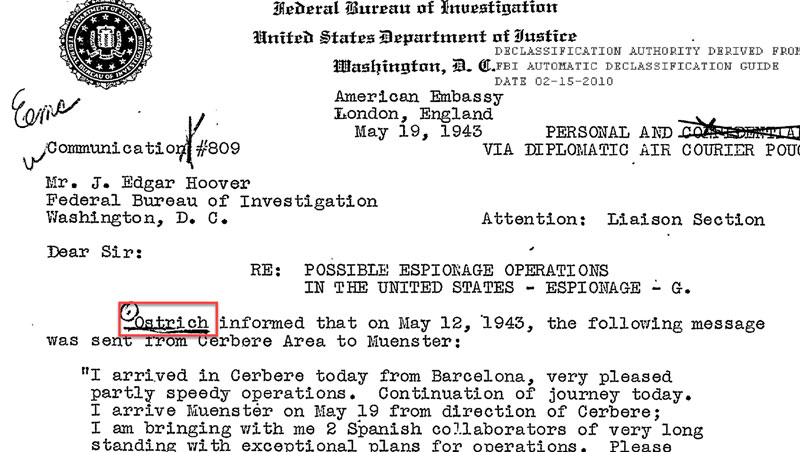

Thurston was clearly sobered by the enormity of his experience. In an urgent cable to Washington on January 10, 1943, he described Ultra, its importance to FBI operations, the role of Bletchley Park, and the set-up at Glenalmond. “I am convinced,” he told Hoover, that “the work at St Albans will be extremely valuable.” He then outlined the extent of his new duties which left him little time to concentrate on Ultra material. To be truly effective, he suggested assigning someone with the skills required to commit full attention to mining treasures from Abwehr messages that he codenamed “Ostrich.” He concluded that an “agent … trained in the work of [the FBI Espionage Section] would be able to originate in the United States a number of cases.”

Little time was wasted seizing on Thurston’s recommendations.

[See related article: FBI Ostrich Files post and view files]

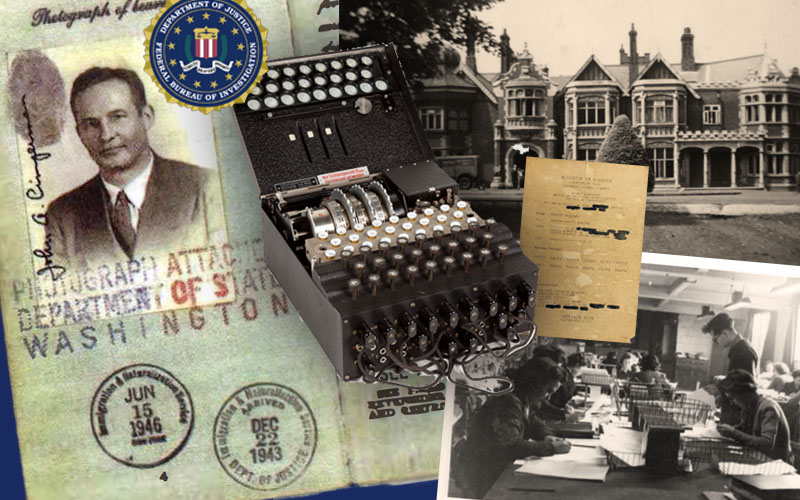

For such a delicate diplomatic mission, Hoover reached down into the heart of his organization for a trusted veteran. At thirty-five years old, and ruggedly handsome at six feet tall, Hoover’s choice was an accomplished investigator with nearly a decade of FBI service. Well-traveled, with a variety of assignments under his belt, the knowledge of counterespionage matters he picked-up at headquarters only added to his already impressive resume.

He was born Janusz Anthony Cimperman on New Year’s Day, 1908, in Barberton, a blue-collar industrial city located in northeast Ohio. Named after his father and known outside the family as “Johnny,” he came from an immigrant couple from Slovenia. Like most men from Barberton’s Slovene community, Mr. Cimperman worked as a laborer for Diamond Match Company, the region’s largest employer.

After high school, Johnny worked for a year before heading south for Macon, Georgia on a football scholarship to Mercer College. Local newspapers for the time were often filled with descriptions of his gridiron heroics, particularly as a punter, against powerhouses like Georgia Tech and the University of Georgia. He joined Blue Delta, a newly formed campus fraternity, and later became chapter president. Four years of college were followed by a second Mercer College scholarship to law school. When not sitting through lectures or pouring over law books he supported himself coaching the junior varsity football team.

As a newly minted lawyer, Cimperman joined the FBI in 1934. From training school, he went west for a two-year assignment to San Francisco. On May 7, 1936, while still a rookie, he distinguished himself by arresting William Dainard, the last remaining fugitive wanted for the kidnapping of nine-year-old George Weyerhaeuser, heir to a vast timber fortune. Having honed the basic skills, he was again moved—this time to Cincinnati where his administrative talents were on display as supervisor of a new resident agency in Columbus, Ohio. After a few months he was back in Cincinnati, this time as Assistant Special Agent in Charge. Next came New York for a two or three week “special assignment” tracking the killer of Peter Levine, nine-year-old son of a wealthy New Rochelle attorney, whose body turned up in Long Island Sound. Two years later, his fourth transfer in six years, took him from New York to Washington, DC.

John Cimperman’s headquarters time was well spent. Along with supervisory duties in the National Defense Division came the occasional public relations detail as well. In one instance, Hoover personally commended him for his careful attention to a congressman invited to address a new agents’ graduation class. Shortly after his arrival, he unexpectedly catapulted into the ranks of a minor FBI celebrity. The Bureau’s firearms training course had only been in operation for four years when Hoover’s Executive Conference met in January 1940 to study ideas for improving it. The goal was to stimulate interest in shooting among agents and produce incentives for attaining better scores. Emerging from these discussions was a unique challenge of sorts. Over a carefully laid out course, timed by an observer, FBI agents would attempt to fire sixty bullets from a six-shot revolver within a defined boundary on a human silhouette target. Cimperman accomplished this extraordinary feat on May 14, 1940, making him the first Special Agent in FBI history to join the illustrious ranks of the newly inaugurated “Possible Club.”

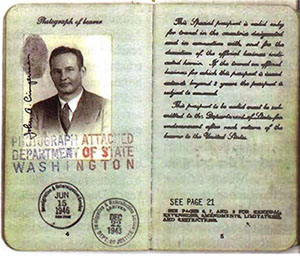

On February 8, 1943, Cimperman was issued a diplomatic passport and number 828 making him the newest member of the Special Intelligence Service. Weeks later, after a grueling trans-Atlantic flying boat journey, Hoover’s man stepped out of the American embassy on to Grosvenor Square for the start of an uneasy journey along the streets of London to Menzies’s Broadway office suite.

***

When Cimperman arrived in London on March 17, 1943, he settled into a local hotel that would be his home for the rest of the war. A week later he boarded a train for a thirty-minute trip to St Albans and then a short bus ride to Glenalmond. His morning route changed three months later when he started traveling to Whitehall. In June 1943, MI6 opened a new library at its Broadway headquarters, separate from the Central Registry, to process Ostrich.

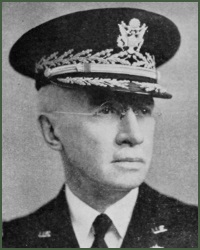

The FBI’s plan to read the enemy’s mind nearly derailed before it started. Cimperman arrived in London in the midst of major policy changes regarding the distribution of Ostrich. General Eisenhower was first briefed on it personally by Winston Churchill in August 1942, just three months before he was to lead the Allied invasion of North Africa. With the Americans now in Ultra’s inner circle, responsibility for control of American access to the miracle source fell to sixty-three-year-old, Major General George Veazey Strong. A West Pointer with a law degree, Strong had been soldiering for nearly forty years before becoming assistant chief of staff for intelligence. Like the British, he too was concerned about the source’s fragility and the need for careful attention to its handling.

These concerns prompted him to impose tight restrictions on what Cimperman could examine. Topping the denied list were Japanese diplomatic messages, what the British called “Black Jumbo” or “BJs.” Next came Italian ciphers filled with information vital to SIS investigations in Latin America. For some time, the British had been digesting valuable data plucked from communications sent between Berlin, Madrid and Lisbon as well as Nazi embassies and consulates in Latin America. Strong added these to the list along with key Japanese circuits between Buenos Aires and Tokyo.

Next, he turned to what the Bureau’s representative could access. Cimperman could only examine messages containing information “over which the Bureau had primary jurisdiction either in the United States or South America.” They had to be in paraphrased form omitting all codenames, true names, and any times, dates or places for fear that they could offer hints about the codebreaking success. Further clamps included data of an “operational character” meaning the, all-important, “preamble.” This was the heading of a message that contained a group number, circuit indicator, frequency, originator of the message and destination, along with the date and time of transmission.

Despite these severe restrictions, Cimperman soon found his ace in the hole. Strong had overreached himself (Orders can be issued but carrying them out was a different thing. Under the general’s rules, a British clerk first had to determine what messages to show to Cimperman. Next, she had to cover the preambles or remove them altogether before typing a paraphrased version of a message for bis examination. Cimperman shrewdly understood that he had only to wait for library officials to recognize that Strong’s order would be impossible to carry out. Staffing was an acute problem and compliance meant a diversion of resources that MI6 did not possess.

Gradually, the British began ignoring Strong’s instructions. As a compromise, Cimperman could read all messages in their entirety. In return, he was honor bound to “entirely ignore” the preamble and transmit only a paraphrased version (prepared by Cimperman) to his superiors in Washington. Hoover’s man, of course, agreed.

The Abwehr, convinced that its Enigma produced communications were secure, still included as little identifying information as possible in them. A message generally contained only a line or two, sometimes three or four, with cryptic instructions or questions that gave little away. After sampling a few, Cimperman recognized that under Strong’s rules any information sent to Washington would have little value rendering them virtually worthless. “Only a smattering or infinitesimal portion of information,” he warned Hoover, “could be forwarded to the Bureau and used as a basis for an active and possibly extensive investigation.”

Cimperman clearly understood the reality facing him. If Ostrich was going to be useful to the FBI, he would have to ignore his agreement with the British.

He now had a new mission, one that would force him to feign paraphrasing and secretly copy verbatim transcripts of the entire message for delivery to Washington. Doing so, however, would be perilous.

***

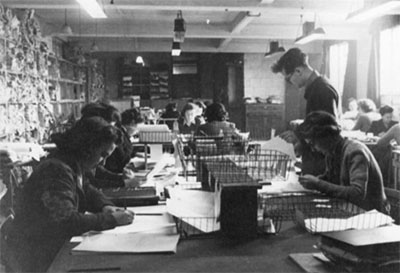

Cimperman worked in the library’s Card Index Section which processed stacks of legal-sized translation sheets listing as many as five messages per page. They were grouped in no particular order with Bletchley Park sending them daily as they were intercepted, decoded, and then translated. Cimperman received these sheets as well. Every day he scanned them for clues to German intelligence activity in the Western Hemisphere. As he grew more comfortable with everyone, he began making cautious requests for related back traffic through the chief clerk who then checked the archived card files.

Privacy was out of the question. Cimperman worked at a desk in the middle of the room-easily visible to dozens of clerks streaming past him all the time. Every day he ran a gauntlet working shoulder to shoulder with typists pounding out endless numbers of S”X8″ cards for each message which then went to the chief clerk for indexing and filing. Sitting there, amidst the busyness, Cimperman became a study in cool nonchalance, nodding, smiling, pretending to paraphrase, while trying to capture an entire message—always jittery that at any moment he might be caught.

Privacy was out of the question. Cimperman worked at a desk in the middle of the room-easily visible to dozens of clerks streaming past him all the time. Every day he ran a gauntlet working shoulder to shoulder with typists pounding out endless numbers of S”X8″ cards for each message which then went to the chief clerk for indexing and filing. Sitting there, amidst the busyness, Cimperman became a study in cool nonchalance, nodding, smiling, pretending to paraphrase, while trying to capture an entire message—always jittery that at any moment he might be caught.

After a time, his anxiety mounting, he felt compelled to vent his concerns to Washington. “Surreptitiously obtaining verbatim text messages … are by no means even slightly satisfactory,” he explained. Copying even a short message of only a few lines could “arouse undue suspicion and detection.” Upper most in his mind, he warned Hoover, was a nagging dread that even the slightest misstep could doom his mission and possibly “jeopardize the Bureau’s further access to this source.”

***

Life as an American diplomat quickly forced other duties on the ill-prepared Cimperman. Many an evening was taken up traveling around London from embassy to embassy for obligatory cocktail receptions or dinner parties—all in an effort to “promote cooperation and goodwill.” Never a drinker and unaccustomed, as he was, to moving in such circles he nonetheless experienced a number of firsts. After investing in a tuxedo and a few tips on diplomatic etiquette, he sampled his first martini. A second one “about floored me,” he later recalled.

As he grew in experience, these official soirees gradually proved useful for him. As the British warmed to the FBI agent from Ohio, he began cultivating important business connections across a wide range of London society. One of them was Ronald Thomas Reed, known to all as “Ronnie.” Reed was a well-regarded electronics engineer with the British Broadcasting Corporation and inventor of the “Baird Televisor,” an early form of television. During the war he worked for MI5 handling an infamous thief and scoundrel turned double agent, Eddie Chapman, codenamed “Zigzag.” Another was Cyril Mills, a MI5 officer and scion of a wealthy circus-owning family. Certainly, one of his most important contacts, however, was Guy Liddell, an Englishman at the head of wartime counterespionage with MI5, still considered by many today as Britain’s finest counterintelligence officer.

[See related article: The Guy Lidell Diaries]

Others would become lifelong friends. One was Sir Norman Huibert. A member of the House of Commons since 1934, Hulbert was an RAF Wing Commander during he war and post-war chairman of several companies including the British Steel Construction Corporation. Another was the widely popular British journalist and literary critic, Dame Rebecca West, author of two major works on the history and culture of Yugoslavia. His dearest friend, however, was Sir Eric Jones. Son of a wealthy fabric manufacturer he, like Hulbert, was also an RAF officer. In 1942, he was assigned to Hut 3 [Luftwaffe ciphers] at Bletchley Park. After the war, Jones eschewed a return to business for a career in communications intelligence rising to the head of Government Communications Headquarters during the 1950s. Not all of Cimperman’s new friends, however, proved so lofty. Two of them, MI5’s Anthony Blunt and Kim Philby of MI6, are still vilified today as members of the notorious Cambridge Spy Ring.

***

It did not take long before Cimperman found himself living a double life. Days spent stealing Ostrich messages from secret British archives were followed by evenings filled with Anglo-American bonhomie and toasts all around to victory with his wartime partners.

As days passed into weeks and then months the mounting pressure of this routine began to wear on him. The frenetic pace of his cat and mouse existence had become crushing, he wrote to his sister. It was much faster than “my poor body could handle.”

Yet, aside from endless rounds of cocktail parties there was nothing to do. Compounding the stress was a ghostly gloom cast by the nightly black-out. There was also a lack of recreation and entertainment opportunities coupled with food rationing. And then there were the sudden screeches of sirens signaling an imminent aerial attack-all producing a city on edge and Londoners battling “frayed or shattered nerves.”

To recover some sense of sanity, he began scaling back on the social whirlwind replacing it with more singular pursuits. “I just had to develop night hobbies,” he recalled years later, “to keep me occupied along clean and healthful lines.”

What prompted it is unknown, but one day he bought a sketchbook and charcoal and started drawing. Starting with simple doodles, he soon graduated to the more sophisticated medium of pastels using pastel sticks to create pictures that were pale in color. As his confidence grew so too did his artistic ambition. It wasn’t long before his tiny hotel room had morphed into an art studio illuminated with watercolors which he painted from pigments suspended in water-based solutions.

A second outlet was a return to an old love, golf. Through the embassy he joined the Moor Park Golf Club where he spent many enjoyable weekend hours. It was a beautiful course, situated on an estate close to London, anchored by a mansion dating back to the seventeenth century. Cimperman first took up the game as a teenager while working as a caddy at local Barberton country clubs. In a short time, he became a local champion and continued to play regularly through college and law school. After years of constant travel with the FBI he took out his clubs again during his Washington, DC days. Soon he had recaptured his skills and, with an FBI foursome, he won the Washington Star trophy in 1941 as the federal government’s best golf team.

Transmitting Ostrich material across the Atlantic was always dicey for Cimperman. Rather than risk exposure with State Department communications and refusing to use Army channels for fear of alerting Strong, (FBI London legal attaches had no independent wireless system) he relied instead on the slow, but secure, diplomatic mail bag for all Ostrich correspondence.

This system changed in November 1943 when MI6’s leadership forced Hoover to sign a special agreement. Starting in December 1943, all paraphrased messages to Washington would go through British channels.

This sudden British decision was rooted in serious missteps in Washington. From the start of his mission, Cimperman had been trying unsuccessfully to educate FBI officials on the strengths and limitations of Ostrich. Part of the problem derived from his remarkable success during those first few months in London. By January 1944, he had provided Washington with details of the German espionage systems at key Abwehr posts in Madrid, Barcelona, and Lisbon. They included identities of leading personnel along with their cover names, duties, and accompanying biographies. Added to this treasure trove was a similar breakdown of Abwehr headquarters organizational structure in Berlin and the heads of each section. These successes had only wetted the FBl’s appetite for more information than he could deliver. Even the laboratory staff demanded more details under an unrealistic belief that it could break the Enigma riddle.

While his efforts in London were producing remarkable results at home, Washington failed to grasp the fact that Ostrich was a unique source that could not be interrogated for new leads. The oracle followed its own schedule speaking when it wished to do so, he explained. Only “waiting and patience” would produce success.

At the same time, he was also keeping-up efforts to sensitize his bosses to the complex security regimen created by the British to guard the code breaking miracle from discovery by the enemy. So concerned was he, in fact, that, at one point, he suggested returning to Washington to deliver a personal briefing.

Distribution of Ultra intelligence was narrowly channeled, he explained, only to senior military commanders and select government officials for maximum value, without revealing a hint as to the source’s identity. Cimperman urged his FBI bosses to follow this same strict British model (for his own protection as well) when sending material to FBI field divisions. He then added that under no circumstance should Ostrich serve as a basis for interviews or interrogations nor shared with foreign liaison partners or other government agencies.

It took less than a year for Cimperman’s failed warnings to come back to haunt him. “Several cases,” he reported in January 1944, predicated on Ostrich, had been discussed with William Stephenson’s staff resulting in “untimely” disclosures of German cover names which he had copied for Washington. Now alerted to Cimperman’s violation of his agreement, Stephenson notified London prompting an immediate complaint to Thurston. For J. Edgar Hoover’s two personal envoys, the entire contretemps proved “very embarrassing.” Only after profuse apologies accompanied by “additional assurances” of compliance with British ground rules was disaster narrowly averted.

For the resourceful Cimperman, a new and more dangerous threat now loomed ahead. With little warning, he faced the prospect of having to prepare sanitized versions of messages for passage to the FBI through British channels and verbatim copies for Hoover which he would have to smuggle out of the library under the noses of a suspicious staff.

J. Edgar Hoover was keenly aware of the extraordinary value of the “most secret source” and the grave risks his man in London was taking every day to exploit it in a brief letter of “personal appreciation” penned to Cimperman in early 1944, the FBI director gave voice to his feelings. In it he acknowledged the “handicaps” John faced along with the “initiative and willingness” he displayed in gathering British secrets “without embarrassment.” Hoover closed with a tip of his hat to Cimperman. Without saying so, he conceded the blunders at home in dealing with the source’s treasures. But that was about to change. Future FBI handling of the source, he wrote, would be held in the “highest confidence in accordance with your suggestion.” (Italics Added)

As the new year came and went, London life for Johnny Cimperman had turned into a diplomatic high-wire act; one that he successfully navigated for the remainder of the war.

***

The world of the Cimperman family of Ohio was always deeply rooted in the Roman Catholic tradition and, for John, his faith remained central to him throughout his life. As he grew up, distractions came along that took him in other directions. After settling in war ravaged London, however, this began to change. Along with painting and golf he once again returned to the comfort of his church. It was a decision that saved his life.

It was a Sunday morning in the spring of 1945, the war in Europe was nearing an end, when he awakened early to attend mass at a nearby church. In the middle of the service, the congregation suddenly alerted to an eerie and now all too familiar sound overhead.

What they heard was the motor of an Aggregat 4 or Vergeltwaffe 2 better known as the V2. At forty-five feet long and weighing more than twenty-seven thousand pounds, it carried an explosive payload in excess of one ton. Moving at almost five times the speed of sound, far faster than any Allied fighter aircraft, it impacted the ground at nearly 1800 miles per hour. The V2 was Hitler’s “vengeance weapon” built to terrorize British civilians for the Allied bombing of German cities.

A moment later the shaken congregation felt the thud of the explosion followed immediately by strange gravelly sounds of debris striking the roof of the church. After the service (and a prayer of thanksgiving for sparing their lives) Cimperman made his way back six blocks to his hotel where he stumbled upon a large crowd gazing down into a massive crater produced by the missile’s impact. Moments later he found the door to his room off its hinges. Inside was a scene of devastation. The force of the blast had shattered the windows spewing shards of glass everywhere. Dust and dirt still filled the air. Everything was destroyed. He called it a “complete mess.”

Even a month later, he was still shaken by the experience. In a letter to his sister, Mary, reflecting on the almost unthinkable “what if,” he called his decision to leave early for mass an “act of God.” Then in a chilling afterthought he offered further thanks that Hitler “didn’t decide to use gas.”

John was the second of three children with his brother, called “Frankie,” the baby of the family. The two men had always been close. “I loved my kid brother,” he once recalled, “and I know he idolized me.” After joining the FBI, he helped support his parents and paid Frank’s college costs. It was always the brothers’ plan to start a business together, but funds never seemed to be there. During the war, John had saved nearly ten thousand dollars which he had earmarked to underwrite their dream. But it was not to be. Sergeant Frank Martin Cimperman, attached to General George Patton’s Third Army, was killed in action on September 10, 1944, somewhere near the French city of Nancy. He was thirty-one years old.

John remembered the moment he learned of Frank’s death calling it the “saddest of my life.” Later he wrote that he “still pays homage to [Frank] on the 10th of every month and knows that he is interceding on my behalf.” Adding to his already profound grief was news that probably tore him up even further. The two brothers hadn’t seen each other since before John’s posting to London. As he later learned, Frank had been nearby in England for a period of training, but John never knew it due to wartime secrecy.

***

John Cimperman was the only FBI representative in London at the end of the war. Arthur Thurston, the agent who first learned about Ostrich, had departed for Kunming, China in early 1944 as a naval officer with the Office of Strategic Services supporting General Clair Chennault’s Flying Tiger force. His replacement was M. Joseph Lynch, a veteran Legal Attache with four years of service at America’s embassy in Ottawa, Canada. He wasn’t there long before a family crisis forced his return to the United States leaving Cimperman to carry on alone.

Life for John had reached a crossroad. He had volunteered for the London assignment to “do my bit” for the war effort and now it was over. What was next for him? He always had plans for the future, he once said, “but they only included my brother.” Now he was gone.

Instead of returning home, he decided stay a while longer carrying on his FBI duties in London until he could figure out what to do next. That little while would last for the next fourteen years. As Hoover’s only London representative, he would witness the most momentous events in the FBI’s Cold War history. On the personal side, he would marry the love of his life. She was the beautiful and accomplished, Eileen Meehan, a Brooklyn girl, and St John’s University graduate, then working in New York as a buyer for Macy’s Department Store.

In 1959 John retired from the FBI and returned to the United States settling with Eileen and their three children on Long Island. He took a position with the National Broadcasting Company which was embroiled in a nationwide game show cheating scandal. John was named vice-president for standards and practices.

John became ill in 1967 and was soon in and out of hospitals with what was eventually diagnosed as bile duct cancer. Death came peacefully with Eileen at his bedside at New York’s Memorial Sloan Kettering Hospital on February 16, 1968. He had turned sixty years old a month earlier.

A postscript to John Cimperman’s remarkable story came in a rare Western Union telegram delivered just days after his death to the family’s Manhasset, New York home. J. Edgar Hoover had been FBI director for more than four decades and he had a long memory. After nearly twenty-five years of world-shaking events involving the Bureau, he still vividly remembered the enormous wartime risks and sacrifices John took to ensure that the FBI benefited from the fruits of Ostrich—a source the director considered the most important of the war. The contributions he made to the FBI and the country he loved, Hoover wired, “will never be forgotten.” Then he added a final thought—a hope really, that Eileen and the children will forever find solace in the knowledge that John had lived “a full and rewarding life.”

_______________

Dr. Raymond Batvinis is a historian and educator specializing in the discipline of counterintelligence as a function of statecraft. For twenty-five years (1972-1997) Dr. Batvinis was a Special Agent of the FBI concentrating on counterintelligence and counterterrorism matters. His assignments included the Washington Field Office and the Intelligence Division’s Training Unit at FBI headquarters. Later he served in the Baltimore Division as a Supervisory Special Agent where he supervised the espionage investigations of Ronald Pelton, John and Michael Walker, Thomas Dolce, and Daniel Walter Richardson.

Following 9/11, Dr. Batvinis returned to the FBI for three years managing a team of former FBI agents and CIA officers who taught the Basic Counterintelligence Course at the FBI Academy. In addition to authoring scholarly articles, he has contributed to the Oxford History of Intelligence, an anthology of essays, published in 2009 by Oxford University Press. He has produced two books on the history of the FBl’s counterintelligence program. The Origins of FBI Counterintelligence, (University Press of Kansas [UPK], 2007), and Hoover’s Secret War Against Axis Spies, (UPK, 2014). He is currently writing a biography of William Weisband, an early Cold War American spy, while completing the third of a three volume history of the FBl’s activities during World War II.

You must be logged in to post a comment.