Three FBI history articles concerning the FBI’s activities in Honolulu, Hawaii during World War II were published in the December 2016 issue of The Grapevine, a publication of the the Society of Former Special Agents of the FBI, in honor of the 75th anniversary of Pearl Harbor:

FBI Grapevine December 2016 History Articles (pdf)

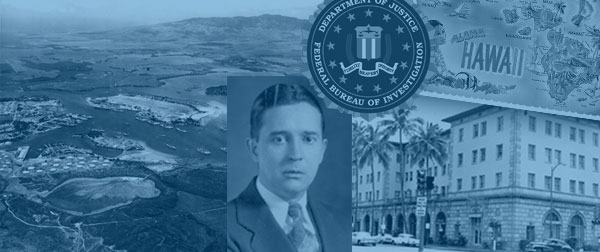

Our Man of Peace in a Time of War — SAC Honolulu Robert Shivers during World War II, by R. Jean Gray (FBI 1955-1984)

December 7, 1941, the “day that will live in infamy,” exploded on the United States igniting hysterical passions.

December 7, 1941, the “day that will live in infamy,” exploded on the United States igniting hysterical passions.

General John L. DeWitt, Western Defense Commander, U.S. Army, filed a report accusing Japanese Americans of engaging in espionage and disloyal conduct. Japanese Americans were said to be signaling with lights and by radio to Japanese submarines lying off the West Coast.

Less than three months after General DeWitt’s warning, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 on February 19, 1942, which empowered the Secretary of War to single out Japanese Americans, expel them from their homes and businesses, and incarcerate them in internment camps. Approximately 120,000 Japanese American men, women and children in the states of California, Oregon and Washington were rounded up. Without specific charges or hearings, the government herded them out to the remotest parts of Utah, California, Arizona, Wyoming and Arkansas, where they lived in barracks and tents (with little privacy), surrounded by barbed wire and watched over by armed sentry guards.

General DeWitt’s reports of Japanese Americans’ disloyalty were, however, being disputed. FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover sent a secret six-page memo to Attorney General Francis Biddle in which he ridiculed General DeWitt’s conclusions. Hoover said, “Every complaint in this regard has been investigated, but in no case has any information been obtained which would substantiate the allegation.” AG Biddle and Colorado Governor Ralph L. Carr agreed with the Director.

Nevertheless, the government convinced the U.S. Supreme Court that the Japanese Americans were security risks, and so it was a military necessity to round them up and incarcerate them. The Justice Department attorneys were aware that General DeWitt’s allegations were “in conflict with information in possession of the Department of Justice.” (Source: Asian American Studies Institute)

Mr. Hoover was instructed to comply. Fortunately, the Director had already selected an exceptional gentleman to reopen the Honolulu FBI Office as the clouds of war gathered — SAC Robert L. Shivers. . . . (read the rest)

“Just My Luck” by Ray Batvinis (FBI 1972-1997)

. . . Alone on the morning of Dec. 7, in the cramped, makeshift radio room, FBI radio technician Dwayne Logan Eskridge began sending test messages to Jim Corbitt, a radio technician standing by at the new San Diego relay station. Alerted by sounds of explosions at 7:55 am, Eskridge and Frank Sullivan, another young FBI office clerk, ran up the stairs to the roof, where they were transfixed at the sight of fighter planes with big red zeros plainly visible on their wings skirting just a few feet overhead, heading in the direction of the Navy anchorage at Pearl Harbor.

A half a century later Eskridge still recalled his disbelief that he could clearly see the pilots’ facial features through the canopy as they zoomed past. Quickly gathering his wits, Eskridge raced back to his radio, hoping that Corbitt was still at the other end to receive his warning that the United States was under Japanese attack. As the deafening noise increased, Eskridge frantically flashed, “WFBB from WFNB, if you are still there, stand by for a very urgent and important message.”

After moments of seemingly endless agony Corbitt flashed his response. Eskridge then tapped out the attack message to the mainland, which was immediately relayed to Washington. Eskridge, the only radio technician in the office, remained at his station for the next 62 hours. . . . (read more on page 11)

Ray Batvinis on the roof of the Dillingham Building where the original FBI office was located on the day of the attack. This is the view Eskridge saw when he ran to the roof after hearing the sounds of explosions and planes flying overhead. Over Ray’s shoulder is the Aloha Tower with Pearl Harbor in the foreground. Eskridge would have seen Japanese fighter planes whizzing by him and black smoke rising up in the distance. He may have even began getting whiffs of the odor of the burning oil fueling the fire.

Ray Batvinis on the roof of the Dillingham Building where the original FBI office was located on the day of the attack. This is the view Eskridge saw when he ran to the roof after hearing the sounds of explosions and planes flying overhead. Over Ray’s shoulder is the Aloha Tower with Pearl Harbor in the foreground. Eskridge would have seen Japanese fighter planes whizzing by him and black smoke rising up in the distance. He may have even began getting whiffs of the odor of the burning oil fueling the fire.

“When Destiny Commands” by Ray Batvinis

“A Day that will live in infamy.” Today, every American instantly recognizes that most memorable phrase from President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s speech on Monday, December 8, 1941 before a joint session of Congress just one day after the surprise Japanese attack on the U.S. naval anchorage at Pearl Harbor, HI. Giving voice to an unspeakable tragedy that cost more than 2,400 lives, the president’s stirring remarks launched America into a war to the end with the Empire of Japan.

It was the history-making enormity of that event 75 years ago this month that brought together the FBI’s Honolulu Division with the Society of Former Special Agents of the FBI for a conference on November 21, 2016. Following welcoming remarks by Paul Delacourt, the Special Agent in Charge, Daniel Martinez offered the audience a fascinating look at Japanese espionage in and around Honolulu in the days and weeks leading up to the attack. Mr. Martinez, an officer with the National Park Service, is the Chief Historian with the World War II Valor in the Pacific National Monument — the home of the USS Arizona Memorial.

His remarks focused on Tadeshi Morimura, a 27-year-old Japanese vice-consul who had only arrived at the consulate in March 1941. Morimura, was, in fact, Tadeshi Yoshikawa, a 1933 graduate of the Japanese naval academy and an intelligence officer. Precluded from active combat for health reasons, Yoshikawa moved into intelligence work in the mid-30s where he quickly began devouring every available source on the U.S. Navy and becoming his service’s top expert in the process. As Mr. Martinez noted, Yoshikawa’s remarkable intelligence coup at Pearl Harbor violated no U.S. laws. His success came from what today’s intelligence professionals call “open source” collection. . . . .

. . . . In my follow-on remarks, I tried to build on Mr. Martinez’s presentation by describing the difficult mission Robert L. Shivers faced in Hawaii. I reminded the audience that while U.S. military intelligence officials questioned the loyalty of the Japanese community in Hawaii, so too did Yoshikawa. In a 1960 memoir about his Honolulu mission, he suggested that Hawaii should have been the “easiest place” to conduct espionage with such a large Japanese population. What he found was just the opposite. “These men of influence and character who might have assisted me in my secret mission” he wrote, “were unanimously uncooperative.” I ended with the thought that as the awful day approached, both the Japanese and U.S. governments did agree on one thing — neither trusted the Japanese community in Hawaii. . . . (read more on page 13)

The Society of Former Special Agents of the Federal Bureau of Investigation presented the FBI’s Honolulu Division with a plaque honoring Mr. Shivers for his contributions to our nation’s history. (L-R: Daniel Martinez, SAC Paul Delacourt and Ray Batvinis)

The plaque reads:

Robert L. Shivers

In recognition of Robert L. Shivers for

undaunted courage and leadership

under fire that he demonstrated as the

Special Agent in Charge of the FBI’s

Honolulu Division on December 7,

1941 and during the perilous weeks

that followed.

This plaque further honors Mr.

Shivers for his heroic protection of

thousands of Japanese men, women

and children residing in the Hawaiian

Islands from arrest and wartime

internment.

Presented this day, December 7,

2016, to the men and women of the

Honolulu Division of the FBI by the

Society of Former Special Agents of

the Federal Bureau of Investigation.

You must be logged in to post a comment.