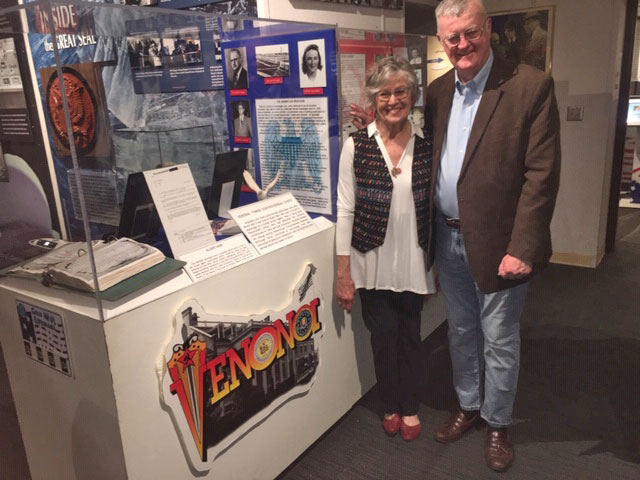

I spent a terrific few hours the morning of 10 May 2019 at the National Cryptologic Museum chatting with Tanya Cimonetti and her husband, Bill. The name is probably unrecognizable to you, but Tanya’s maiden name is Tanya Zubko. She is the daughter of the late Leonard Zubko.

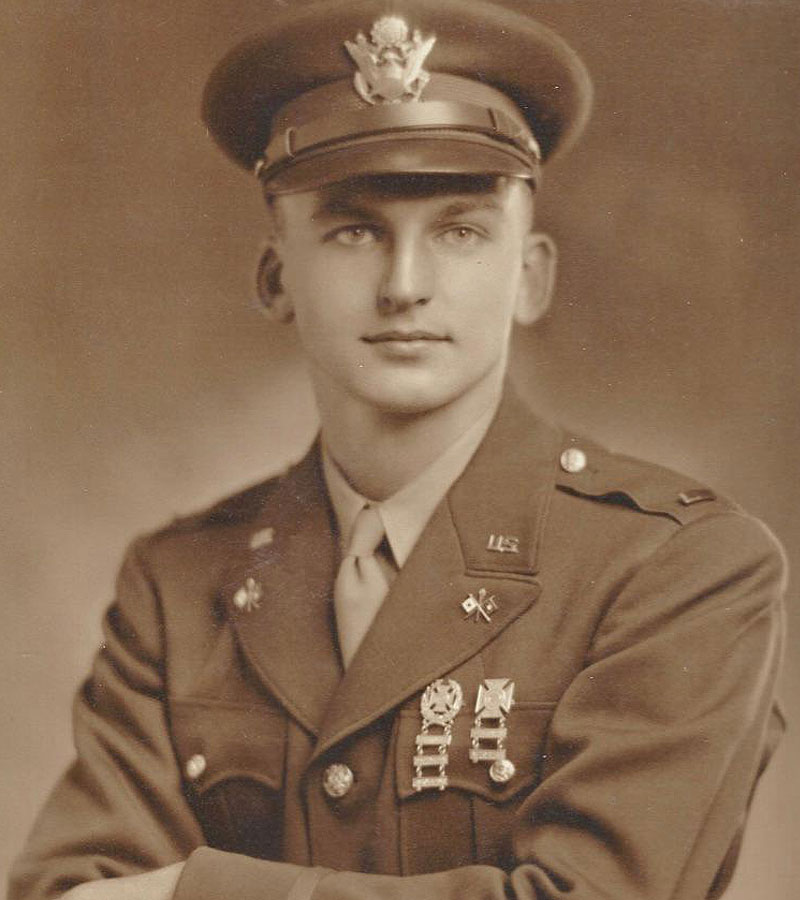

Still in the dark? Well, Lieutenant Leonard Zubko, U.S. Army, was one of the first two persons assigned by the Army Security Agency (ASA) to tackle the Venona Program; what today is regarded as the most successful codebreaking achievement against the Russians in the twentieth century.

I entered Tanya’s orbit in the usual way that historians do their work. In the course of researching a book I’m writing, I ran across a brief reference to her Dad in the official history of the Venona program written by Robert Louis Benson, an NSA historian. A little online searching led to Leonard’s obituary and Tanya as a descendant along with the town where she lived. A telephone call or two later and VOILA – a connection.

What was so gratifying for me was offering Tanya some insight about her Dad’s role in the opening phase of the Venona Program.

Leonard Martin Zubko was a native of Kearney, New Jersey, born the second son of a couple from the cities of Pinsk and Minsk in what today is Byelorussia.

During his four years at Kearney High School he was an award-winning swimmer and outstanding scholar graduating near the top of his class as the salutatorian.

In the summer of 1942, after marrying his sweetheart, Frances, and graduating from Rutgers University with a mechanical engineering degree Leonard headed off to Georgia (he had been in ROTC at Rutgers) for advanced infantry training at Fort Benning.

He was trained and ready to lead troops in combat when he was abruptly sidetracked in November 1942 with orders for Arlington Hall, ASA’s new headquarters, located in a former Virginia girls’ school, just miles from Washington across the Potomac River. Len never knew who selected him for the assignment or how he was chosen but it was a good bet that the Russian language, spoken in the Zubko household since before his birth, had something to do with it.

On February 1, 1943 he was teamed with a young woman fresh from a teaching job in Lynchburg, Virginia named Gene Grabeel. Both of them, still in a daze and with little explanation, were thrown into a world of utmost secrecy, even by Arlington Hall standards.

Together they were relegated to a drab room with two chairs and a table surrounded by standard brown Metal Art file cabinets lining all four walls. The drawers, they soon discovered, were filled to the bursting point with tens of thousands of encrypted cables sent between Moscow and its diplomatic missions in the United States; all collected by censorship authorities since the start of the European war in September 1939. Their job — decode them.

One major problem was immediately evident. Neither Leonard nor Gene had ever decoded a thing, nor did they have any idea how or where to start. Undeterred, the two began sorting the messages based on the particular diplomatic mission designations and the cryptographic system or subscriber used by the Russians.

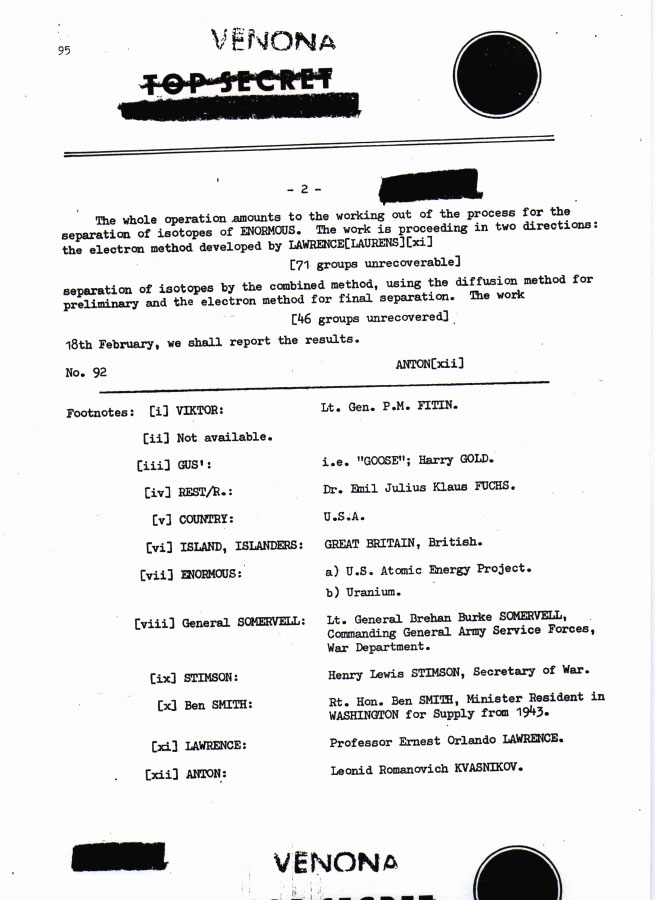

Their work laid the groundwork for the stunning revelations that emerged just a few years later. What they had discovered were the five cryptographic systems used by different subscribers. One of them, the Soviet Trade Mission, managed the complex system of Lend-Lease. The others were used by the KGB, the espionage service, both GRU army and navy spy agencies, and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

As Leonard and Gene sat hunched over mounds of paper, they faced a heavy burden of being forced to talk only in whispers and hushed tones. Prompting their near silent exchanges was a constant threat to their secret mission lurking just a few feet away. His name was Geoffrey Stephens. A serving major in the British army, Stephens was assigned to Arlington Hall as a representative of Bletchley Park, Britain’s codebreaking center located on a country estate about forty miles north of London.

It is unimaginable today, to think that ASA leadership had allowed two Americans, both barely into their twenties, inexperienced, with virtually no security training, to struggle with a top-secret project (Venona was off-limits to the British at this early stage) while a seasoned military intelligence veteran sat nearby carefully observing their every move.

Here is where the story gets a little fuzzy. Just a few months after they started work, the Venona Program was abruptly shut down. No one is certain why, but the speculation is that Leonard and Stephens, both trained as infantry men, became friendly, producing fears that the British Major might learn about Grabeel and Zubko’s mission.

Leonard, having little interest in codebreaking and feeling he had little talent for it, was anxious to escape Arlington Hall and get into the war. In March 1943 he got his wish with a transfer to Dyersburg Army Airfield in rural Tennessee for training as an air traffic controller with the 346th Heavy Bomb Group.

Following graduation came three more months as an instructor before his deployment overseas in January 1944 to the China-Burma-India Theater. For the next two years he handled the nerve-wracking mission of controlling aircraft he never saw carrying vitally needed supplies over the towering Himalaya Mountains to Allied forces battling the Japanese in China and Southeast Asia.

By the end of the war he was in Kunming, China, as the chief air traffic control officer managing the grueling twenty-four-a-day air supply operation over China.

After his return to the United States in December 1945 and his subsequent discharge, Major Leonard Zubko moved to Troy, New York and Rensselaer Polytechnical Institute for a graduate degree in mechanical engineering.

Around the time that Meredith Gardner, ASA’s brilliant codebreaker, was cracking Venona’s secrets and exposing Moscow’s vast collection of spies in the United States, Len was a professor teaching gas dynamics at the University of Illinois.

Later he joined the General Electric Company where he designed jet engines and managed a variety of aerospace engineering projects.

In an ironic historical twist, thirty years after his Arlington Hall assignment, General Electric sent Len to Moscow in 1973 as the company’s first permanent business representative in the Soviet Union. Two years later he was reassigned to Brussels for a year before returning to the United States.

After more than thirty years with General Electric, Len and Frances retired to Mt. Dora, Florida. Frances passed away in 2001 followed by Len five years later after a brief illness on August 21, 2006.

MORE

Venona Documents (NSA)

BOOKS

You must be logged in to post a comment.