Shortly before midnight on December 12, 1941, not yet a week since the surprise Japanese attack on America’s naval base at Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, Judge Mortimer W. Byers asked jury foreman, Edward Logan, to rise and read the verdict. Only a day before, in Berlin’s Reichstag, Adolf Hitler had announced to the world that Germany would join with Japan in making war against America.

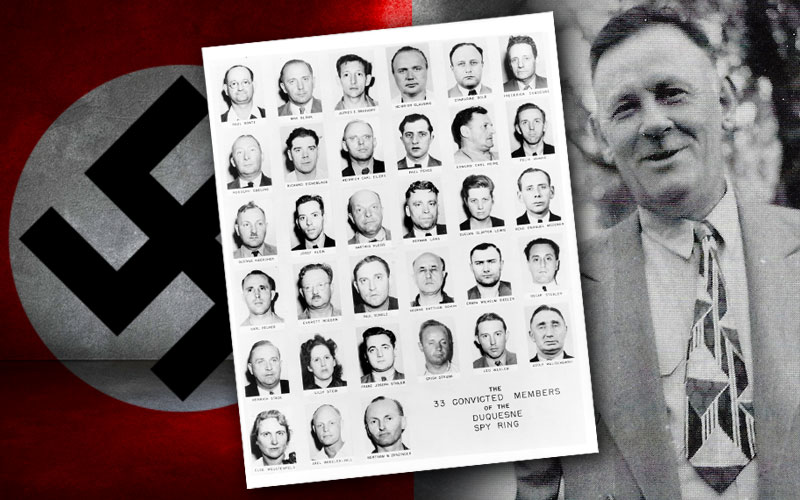

Standing before a packed Brooklyn, New York court room, a somber Logan pronounced fourteen defendants arrayed before him guilty of espionage against the United States. Added to the nineteen who had already pleaded guilty, Logan had unknowingly sealed the fate of German espionage in the United States for the remainder of the war. It was, as one author recorded, “the first US victory of World War II.”1

The story of this victory begins on February 8, 1940 at a quarantine station near New York’s Upper Bay where inspectors conducted checks before ships slipped into New York City piers. Among the officials that day was an FBI agent and another agent from the Department of State both anxiously looking for a passenger who had left Europe a week earlier. After a brief introduction the trio quietly departed the ship and drove to the FBI’s New York office where the stranger spent the next two days disgorging a seemingly preposterous tale.

The mystery man was a forty-year-old American named William Gottlieb Sebold. As one of four children born in Germany to a beer wagon operator, he quit school as a teenager shortly after his father’s death to apprentice as a draftsman in his home city of Mulheim on the Ruhr River. As a draftee in the army during the First World War, Private Sebold struggled to survive eighteen months of trench warfare along the Western Front. After the war, back in Mulheim, he tried to cope with the escalating political and economic turmoil that wracked the new Weimar Republic.

As Sebold’s life grew more desperate he made a bold decision to start fresh in America signing on as a crew member with a ship bound for Houston, Texas. Over the next sixteen years, he married, and led a nomadic existence before settling in San Diego, California for a time with a job in the burgeoning aircraft industry at Consolidated Aircraft Company, producer of the PBY Catalina seaplane.

Away from home for more than a decade and with Europe descending closer to war, Sebold sailed for Germany in January 1939 to visit family.

From the moment he arrived in Mulheim he fell under the watchful eye of the Abwehr, Hitler’s military intelligence service. Over the coming months they questioned him and stole his US passport preventing him from leaving Germany. Then came a demand that he serve as an Abwehr agent in America in exchange for his mother’s security. Having no choice, Sebold reluctantly agreed. A year later, in January 1940, new passport in hand, he made his way to Genoa, Italy where he confided his predicament to the US consul before boarding the SS Washington and an uncertain future in America.

Sitting before slack-jawed agents, Sebold poured out remarkable details.

He recounted his espionage training in Morse Code, short-wave radio operations, encoding and decoding messages, and use of disguises. He was to join the National Guard to access new weapons, seek employment with an aircraft firm while refraining from contacts with local Germans who might draw the attention of authorities. Assigned the alias of “Harry Sawyer,” he was supplied with mail drop addresses in Shanghai, Sao Paolo, and Coimbra, Portugal.

Then came the shocker as he lifted the back plate of his wristwatch to reveal five thumbnail slivers of microphotographs. Under a magnifying glass, FBI agents faintly discerned instructions for assembling a shortwave radio capable of reaching Germany. The others revealed directives for three people living in New York. They were Lilly Stein, an Austrian immigrant and owner of a midtown Manhattan millinery shop, Everett Roeder, an engineer with the Sperry Gyroscope Company living in Merrick, Long Island, and a notorious South African rogue and American resident of forty years named Frederick Duquesne, whose hatred for the British dated back to the Boer War.

Next, he outlined an order to contact someone named Herman Lang, a security officer at the Carl Norden Company in Manhattan which was producing the so-called Norden Bombsight – America’s most secret weapon at the time. He was also instructed to find an amateur radio operator to handle communications.

As if this wasn’t enough to digest, Sebold produced two hidden money pouches given to him before he left Germany. Both contained five hundred dollars (equivalent to $18,000 in 2019). Half was earmarked for the purchase of radio equipment and the other destined for Roeder.

Many years later, one FBI agent summed up the astonishment of everyone who sat in rapt attention listening to Sebold’s tale. “The story, to say the least, seemed preposterous. To send a head spy to the US who did not want to be a spy in the first place and give him information as to the other spies in the US did not make good sense.”2 Yet despite the skepticism, Bill Sebold readily agreed when asked if he would serve as his country’s first true “counterspy.” (The term “double agent” was not in use at that time.)

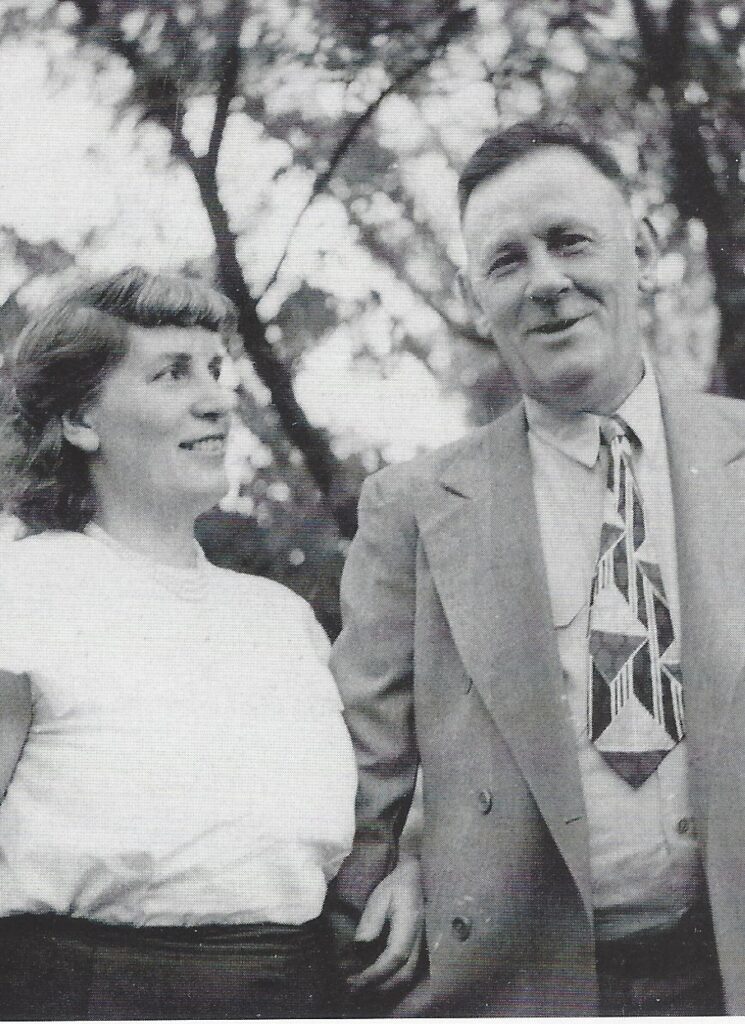

To handle Sebold on a day-to-day basis, J. Edgar Hoover selected a thirty-year old Special Agent named James Claridge Ellsworth then assigned to Los Angeles as the assistant special agent in charge. The choice was not at all a random one. Married with two young children and a member of the Mormon church, he had served as a missionary in Germany for two years during the late 1920s where he immersed himself in the culture and traditions including fluency in the German language. He would remain in New York for the next two years. Decades later Ellsworth would serve as the president of the Society of Former Special Agents of the Federal Bureau of Investigation.

Bill Sebold’s intelligence produced a seismic shift in the way the FBI did business.

From that point on the Bureau intensified investigation of foreign intelligence activities that included use of diplomatic officials on US soil, anonymous spies hiding in the fabric of American society, mail drops in neutral countries, and foreign funds passing through American banks destined for its spies.

Advanced technical procedures were also developed involving shortwave radio communications, large scale telephone and microphone surveillance and new photographic techniques. Hoover’s investigators were soon on the move headed for South America and Asia to track down leads in what became known as the “Ducase.” The three-fold goal: build a prosecutable case, lift the veil of secrecy shrouding German intelligence collection in the Western Hemisphere, and neutralize foreign espionage by controlling their agents in the US.

Within weeks of his first meeting with the FBI, having gained the confidence of Stein, Roeder, Duquesne, and Lang, Sebold established that they were Abwehr agents. J. Edgar Hoover quietly confirmed for President Franklin Roosevelt that the secrets of the Norden Bombsight had been in German hands since 1938.

Over the next three months FBI agents scoured New York for the parts needed to build a working shortwave radio. By early spring the equipment had been installed in a two-room bungalow overlooking the Long Island hamlet of Centerport on the edge of Long Island Sound.

On May 18, 1940, following repeated unsuccessful transmissions, the Centerport radio station crackled to life when Hamburg signaled receipt of a message and the Abwehr’s eagerness to communicate with Sebold. Over the next fourteen months the two stations exchanged more than seven hundred messages producing a windfall of intelligence for American authorities.

Information requirements received at Centerport offered American officials unique insights into Germany’s knowledge gaps about US military activities. Monthly production figures for aircraft rolling off America’s assembly lines and shipments of planes to England were a high priority. Convoy locations, departure schedules and destinations were also vital for Germany’s U-Boat campaign in the Atlantic, as were details about ships like the French liner Normandie and the aircraft carrier Saratoga, suspected of ferrying planes to Great Britain.

Centerport station confirmed what had long been suspected–the intelligence sharing relationship between Germany and Japan. It occurred when Sebold and Roeder met with Takeo Ezima, a Japanese naval officer with diplomatic immunity who had been assigned to New York since 1938. Investigation of Ezima led to Kanegoro Koike, an obscure official at the Japanese consulate in New York, who was found to be the “paymaster of the Imperial Japanese Navy.”3

Along with this intelligence bonanza came an unexpected problem that had to be addressed. Sebold was pivotal to the success of the investigation and to remain believable to the Abwehr he had to pass accurate information to them – information that could be detrimental to Allied interests. In essence then, the question was what intelligence could be safely transmitted to maintain Sebold’s deception without endangering American lives and material.

A top-secret information clearance committee was formed that would make complicated and often risky judgements on what secrets to place in German hands and when to do it. As the case progressed certain facts and figures were deemed too sensitive for passage while other data was cleared with ease. In still others, for example, specifics of Atlantic convoys, the committee authorized passage, yet delayed sufficiently in transmission to allow time for rerouting ships out of harm’s way. This clearance system, which was expanded and further refined during the Second World War, became a fixture of the American intelligence process for decades to come.

One constant headache for the Abwehr was timely transmittal of payments to its American agents. So acute did the problem become that Berlin made the fatal error of asking Sebold for ideas. He proposed the creation of a phony business under his control called the Diesel Research Company. This would allow him to open a legitimate bank account in New York through which a Nazi controlled company could wire funds that he could draw on to make his payments. The concept was immediately accepted in November 1940 making Sebold both the communications link with Germany and its paymaster.

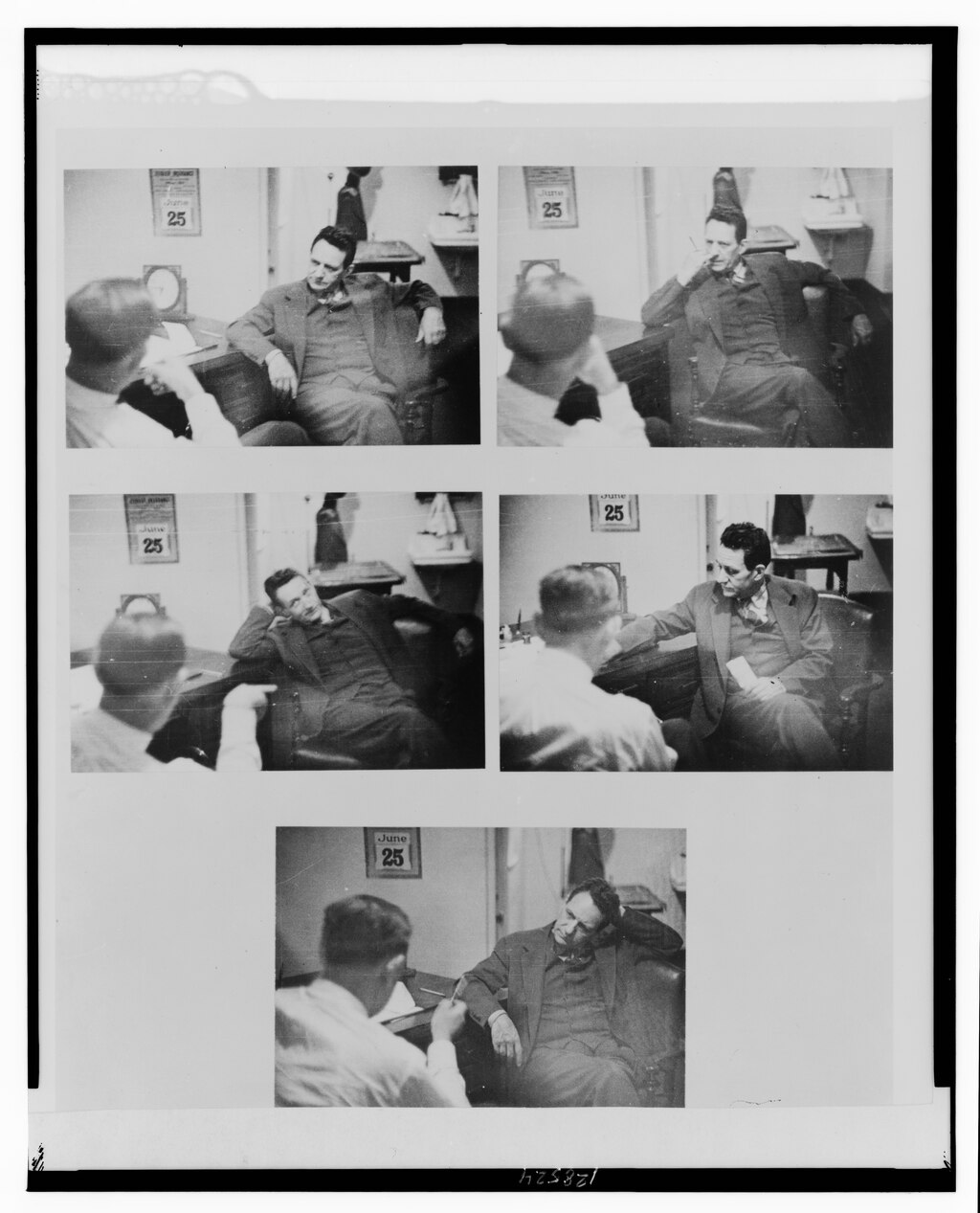

His new midtown Manhattan office soon witnessed German spies disgorging a steady stream of secrets to Sebold in exchange for cash as FBI agents carefully listened through paper thin walls and hidden cameras recorded the action on film for later display to a jury. The long line of interesting characters came from four separate espionage rings independently operating in the US. Among the thirty-three indicted spies were couriers working as ship crew members, a bookkeeper, a businessman from Detroit, a California dentist, the head of Abwehr’s American Marine Division, an airline steward, the owner of a gambling casino along with Stein, Duquesne, Roeder, Lang and dozens of others.

His new midtown Manhattan office soon witnessed German spies disgorging a steady stream of secrets to Sebold in exchange for cash as FBI agents carefully listened through paper thin walls and hidden cameras recorded the action on film for later display to a jury. The long line of interesting characters came from four separate espionage rings independently operating in the US. Among the thirty-three indicted spies were couriers working as ship crew members, a bookkeeper, a businessman from Detroit, a California dentist, the head of Abwehr’s American Marine Division, an airline steward, the owner of a gambling casino along with Stein, Duquesne, Roeder, Lang and dozens of others.

A surprising benefit of this case, not discovered until after the war, occurred following the dragnet arrests beginning on June 29, 1941. German charges d’affaires in Washington, Hans Thomsen, caught off guard by the arrests, had no idea that the spying operation was under way. In a blistering cable to Berlin the furious diplomat minced no words in unleashing his frustration about what he called “such poorly organized operations.” Still not satisfied, Thomsen issued a prophetic warning to his foreign ministry bosses. The irresponsible actions of Hitler’s spies “most likely have not benefited our conduct of the war,” and “may cost us the last remnants of sympathy which we can still muster here in circles, whose political opposition is of interest to us.”4

While Edward Logan’s pronouncement certainly was the “First Victory,” the Allies still faced a bloody three-and-a-half-year conflict against Hitler’s Wehrmacht. But with the verdict, the march to victory had made a formidable start. The Abwehr never recovered from Sebold’s selflessness and courage. The back of German espionage had been broken. Until the end of the war in Europe, Hitler and his Nazi war machine remained blind and deaf to America’s strategic war making plans, production, and strategies.

1. Peter Duffy, Double Agent. New York: Scribner, 2014, 2.

2. Double Agent, 140-141.

3. Raymond J. Batvinis, The Origins of FBI Counterintelligence. Lawrence, Kansas: University Press of Kansas, 2007, 247.

4. The Origins, 255.

Author expresses his appreciation to Peter Duffy for permission to use the Sebold and Ellsworth photos.

You must be logged in to post a comment.