During World War II, FBI agents and radio technicians lived and worked undercover at Benson House, secretly transmitting coded messages that the Nazis believed came from their own spies.

A plaque placed at Benson House in honor of the 70th anniversary of the D-Day invasion recognizes the counterintelligence efforts of FBI employees during WWII.

(FBI) In honor of the 70th anniversary of the D-Day invasion, the FBI last weekend celebrated a landmark that was home to one of the Bureau’s intelligence successes during World War II.

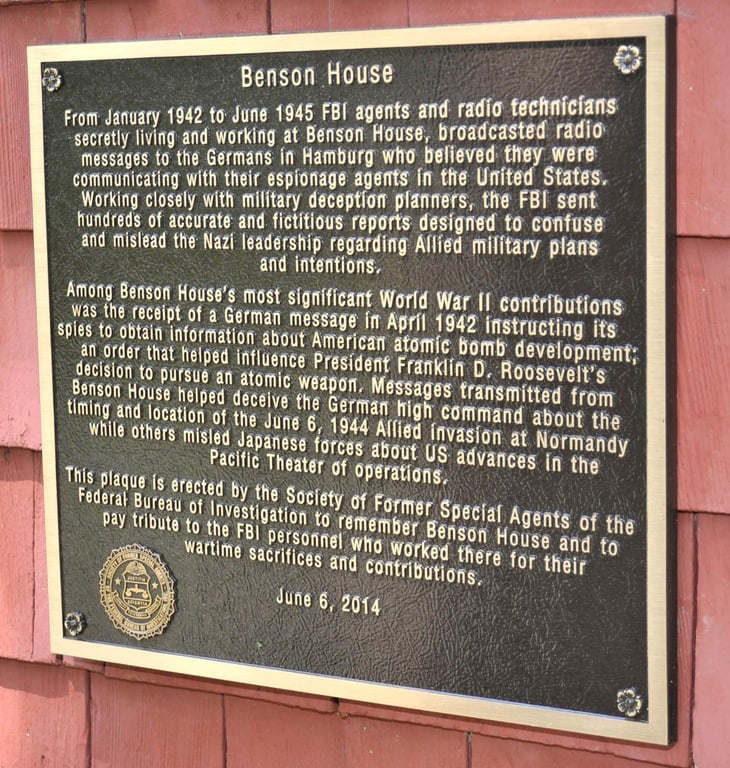

At a ceremony in recognition of the effort of FBI employees during World War II, the Society of Former Special Agents, the Episcopal Diocese of New York, the Suffolk County Historical Society, and the FBI’s New York Division placed a plaque at a quaint building known as Benson House in Wading River, New York, overlooking Long Island Sound.

The Allied effort derived its name from a statement by British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, who said, “In wartime, truth is so precious that she should always be attended by a bodyguard of lies.”

It was there, from January 1942 until the end of the war in Europe in 1945, that FBI agents and radio technicians lived and worked undercover, secretly transmitting coded messages that the Nazis believed came from their own spies operating in New York.

The Nazis believed their operatives were funneling significant details about U.S. forces, munitions, and war preparations.

But in fact, the transmissions were controlled by the FBI—the Nazi spies were FBI double agents. The Bureau’s work—known as Operation Ostrich—was central to our counterintelligence operations throughout the war and was part of a larger effort by Allied Forces to deceive the enemy called Operation Bodyguard.

Misleading Adolf Hitler’s intelligence services was integrated into the long preparation for the June 6, 1944 landing of 160,000 Allied troops in Normandy, France.

Operatives set out to deceive the Nazi leader about the nature and location of the main Allied thrust so that he would be ill-prepared to meet the invasion.

The key to Bodyguard’s success was the Allies’ control of a number of German spies and ability to read coded German messages that confirmed the Nazis didn’t know their agents were compromised.

For the FBI, the initial purpose in participating in the counterintelligence effort was to learn about Nazi espionage—who was involved, how they worked, and what they wanted to know.

Early on, intelligence from one double agent’s transmission indicated the Nazis were very interested in U.S. experiments with atomic energy.

This, in part, spurred U.S. efforts to build the atomic bomb before the Nazis could.

The secretive work at Benson House proved even more valuable because it allowed us to plant misleading information for Nazi officials—essentially controlling what the enemy knew about the U.S. and its state of military readiness.

In the case of Operation Bodyguard, it allowed us to help Allied efforts to protect the D-Day invasion plans.

Even after the fall of Germany in 1945, Nazi intelligence officials believed that the hundreds of messages sent by their spies in the U.S. were real.

The FBI’s efforts to contribute to the Allied “bodyguard of lies” were among the many Bureau intelligence efforts during the war and were surely some of our most significant.

Read more about this story: