On the Spycraft 101 podcast, Justin Black interviewed me about my FBI career, the espionage cases I worked on, as well as my first book, The Origins FBI Counterintelligence.

We had a good conversation and I hope you enjoy it. It’s available on your favorite podcast platform or you can listen here:

–

TRANSCRIPT

Justin Black, Spycraft 101

Since the dawn of civilization, spies of every nation and culture have worked to infiltrate their adversaries and glean the information that will give their side the advantage sky high. The strategies varied and imaginative, and the ultimate sign of success is that no one ever even knew you were there. In each episode, we will explore the moral and ethical gray zones of espionage, where treachery and betrayal go hand in hand with cunning and courage.

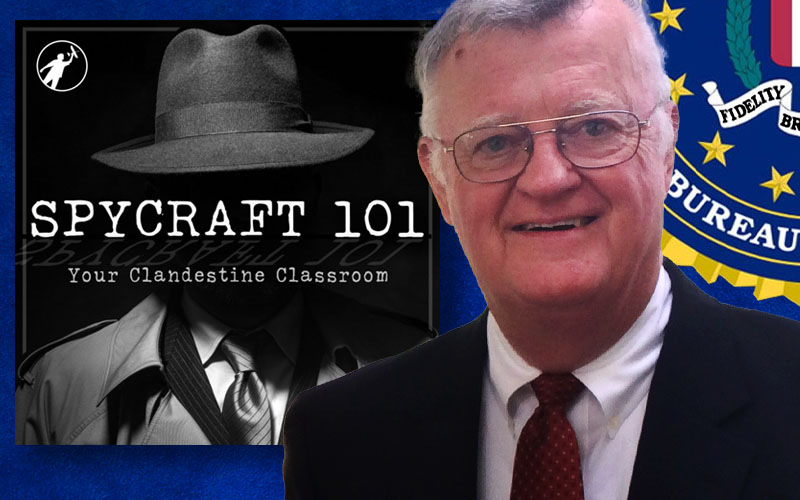

This is the Spycraft 101 podcast. Welcome to your clandestine classroom. This is episode number 66 of the Spycraft 101 podcast. Today I’m speaking with retired FBI Special Agent Raymond J. Batvinis. Raymond served in the FBI for 25 years, from 1972 until 1997, primarily working in counterterrorism and counterintelligence. Shortly after the 911 attacks, he returned to teach the basic counterintelligence course at the FBI Academy at Quantico. During his career, he worked on several very high-profile espionage cases, including the investigations into Ronald Pelton and the Walker spy ring. Since retiring, Raymond has worked tirelessly as a historian, author, and researcher. He’s published a number of scholarly articles on intelligence history and operates the website FBIstudies.com. He’s also published two books since 2007.

I invited Raymond on to the podcast today to discuss one of those books titled The Origins of FBI Counterintelligence. Raymond, first of all, thank you for taking the time to sit down with me today.

Ray Batvinis

Well, thank you for having me. I really appreciate it.

Justin Black, Spycraft 101

Absolutely, absolutely. I’m really glad that I was able to get in contact with you because I think that this is a subject that is long overdue for discussion here. Like I was telling you before we started recording, this is episode number 66, and it feels like I’ve touched on the subject of early days of FBI counterintelligence on a number of occasions, but finally the time was right and the person, the guest was right as well to do, like, a deeper look into this. So I’m glad that we’re here today.

Ray Batvinis

Well, I’m looking forward to it.

Justin Black, Spycraft 101

Great. So like I just said in the intro there, you served as a special agent for 25 years, and then afterwards you became a historian of the profession itself. So at what point did you decide to take up this new second career as a historian. Was it while you were still working with the FBI? Or was it something that you just had a lot of free time to pursue after you retired?

Ray Batvinis

No, I’ve always had a very, very keen interest in the study of history, going back to my high school days. But the launch pad for pursuing my doctorate I got my doctorate in May of 2002 from Catholic University of America in history. But the launch pad really began in the latter part of my FBI career. I didn’t really have any hobbies. My children were above the age where they needed me home at night. And so I began taking the history courses back at the Catholic University, actually even before then at G. W. George Washington University and what was called the Defense Intelligence College at that time. And then I went back part time in one course, one night a week at Catholic University. And it was a hobby. But a hobby became an obsession, and eventually I went for the full product. I took courses, and then by the time I hit the age of 51, I was actually eligible to retire at the age of 51. With 25 years, I retired with the idea that I wanted to do my dissertation. So I did, and I worked part time as a contractor. But for the most part, I worked on my doctoral dissertation. And my first book, The Origins of FBI Counterintelligence, is an outgrowth of that doctoral dissertation.

Justin Black, Spycraft 101

Okay. Wow. That’s wonderful. That’s wonderful. I have to admit that what you said about a hobby growing into an obsession, that kind of struck a chord with me because that is sort of what this has become for me over the past couple of years. It started with me telling a few interesting stories online on social media, and now it’s turned into practically a fulltime job with these interviews that I do and all the articles that I write and that sort of thing. So I’m kind of right there with you in some ways with this interest in this past time turning into something much more than that over time.

Ray Batvinis

Yeah. It’s a great journey, isn’t it?

Justin Black, Spycraft 101

It really is. It is a lot of fun. And I look forward to having even more spare time in the future because my kids aren’t out of the house yet or anything like that. So I do have to divide up my time in some ways, but I shouldn’t say I’m looking for my kids getting out of the house so I can read more books. But I am looking forward to devoting a lot more of my time to this one day, many years in the future, like you’ve been.

Ray Batvinis

I really wish you well with it.

Justin Black, Spycraft 101

Thank you. So with all of this research that you have done. I have to imagine. As someone who’s not never been a part of the FBI. But I would assume the FBI documentation is very thorough going back to the beginning. But did you still find did you still uncover a lot of stuff that was not really well known within the organization or not well documented in published scholarly articles and that sort of thing?

Ray Batvinis

Well, actually, the answer to your question is yes, and we could probably be here for the next 2 hours talking about it. What I discovered is I discovered a number of things, and actually they touch on the first book that I wrote, and that deals with the issue of, for example, Pearl Harbor. The FBI Sac special agent in charge, who was sent to Pearl Harbor to Honolulu, was sent there in 1939. He came from the south. His name was Robert Shivers. And I’ll just give you just a thumbnail sketch.

He was sent there by J. Edgar Hoover in 1939, just the summer before the war broke out, to take the pulse of the Japanese population in the Hawaiian Islands. There were 140,000 Japanese people of Japanese ancestry in the Hawaiian Islands. And it was a very grave concern on the part of National Command Authority that if we ever did go to war with Japan, that they could pose an internal threat toward the military out there and toward the court, toward the nation. It’s a fifth column, so to speak. So Shivers was sent out there, and to be very frank with you, Shivers had never met a Japanese person in his life. He was from the deep south. It was completely alien to him. But he had a certain genius to him. And what he did was he began to develop, if you picture an image of your mind of the Olympic logo, those concentric circles intertwined, and that’s what he did. He developed a series of concentric circles of contacts both in the white community and in the Asian community. That would be the white community. It would be the Polynesian community, the Philippine community, the Japanese community, the Korean community, all of these communities out there that could pose perceived problem. And he worked with the churches out there. He worked with the YMCA, which was very important to the Asian community out there.

And after about a year or two of meetings and getting to know them and traveling throughout the islands, he came to the conclusion that the Japanese out there posed no problem at all. In fact, quite the opposite. They would actually be vigorously supportive if the United States went to war against Japan. They would be vigorously supportive of the US. Position. And he transmitted this information to J. Edgar Hoover throughout the period of time, from 1939 right up to 1941. And then even after 1941, he said, you have nothing to worry about. You can communicate to the military and to the President of the United States that you have nothing to be concerned about.

As a result of that, he’s a great hero in the Hawaiian Islands. Today. He is revered out there. It’s about six years ago, I went out to Honolulu, and I dedicated a plaque in his honor at the FBI office. But when you go and you talk to the people who understand the history of that, he’s a great hero. So that’s one of the very important discoveries that I made while I was doing the research for this book.

Justin Black, Spycraft 101

Wow, that is fascinating. I was not aware of that at all. I’m definitely going to have to look at that after we finish this call. As a matter of fact. That’s really interesting.

Ray Batvinis

Yeah. In fact, the governor, when the governor of Hawaii at the time, actually asked Shivers to take over control of the island, and Shivers says, I can’t do that. And then, of course, what happened is the President, within hours, had it come under military control, and so the commanding general out there became the governor of the island. But it’s a fascinating story that is really not known outside of Hawaii today.

Justin Black, Spycraft 101

Yeah, absolutely. It must not be very well known if I’ve never heard of it before myself. I’ll have to check into that. It’s very cool. So, Raymond, obviously, we’re talking about the origins of FBI counterintelligence here, and it’s really interesting for me to look at the origins of this organization for many reasons, but part of it is because, of course, the very early pioneers, the plank owners, as they’re called, you know, they set the tone for decades to come because they’re creating the culture of the organization. They’re creating the standard operating procedures and everything. So it’s very clear to me from reading through your book that these first agents that you write about really had their work cut out for them, going up against these networks and operations, you know, these foreign networks that were already well in place long before the FBI existed, from countries and governments that were had very well established espionage practices and procedures and experience as well. So it seems like a very, very tough initial climb for the FBI right out of the gate. Would you agree with that?

Ray Batvinis

Oh, I would absolutely agree with it. It was a very, very steep learning curve, and it was steep. It’s interesting that Justin, it was steep, but it was short. In order to answer the question. Let’s go back for a moment to of course. We could go back to the start of the FBI in 1908. But what I’d prefer to do and if you want to go back. We can certainly go back to that. But what I prefer to do is go back to 1924. Because that was the year that J. Edgar Hoover. Who was at the time only 29 years old. He was ordered or made acting director of the Bureau of Investigation. Not federal bureau, but Bureau of Investigations. And the Bureau had just come off of a very — the Bureau and the Department of Justice had just come off of a very serious scandal back in 1920 when they opened the General Intelligence Division. And they were doing, I would call it for general purposes, a vacuum cleaner kind of collection of data on American citizens and aliens in this country. And then what happened was arrests were made of aliens that were going to be deported.

And when the judge looked at the probable cause for the arrest, he dismissed all of the charges, really against most of these aliens. Well, the American public was outraged over this, and there was a furious backlash that the federal government could violate the privacy and civil rights of Americans. They said, that’s not right. So the General Intelligence Division of the Department of Justice was promptly closed down. So by 1924, there was a new regime. Calvin Coolidge was the president, and I can’t think of his first name stone, the Harlan Stone became the general of the United States. Stone was a reformer, and Stone essentially ordered Hoover, as acting director to close any intelligence investigation that was open at the time. So for the most part, 99% of them were closed. So what Hoover then begins to do is reform the Bureau of Investigation, clean out the dead wood, clean out the nepotism, get rid of the lazy people in the organization, and begin to change it by professionalizing it. And this is what he does over the next ten years with a great push. And then, of course, in 1930s is the era of the gangsters.

And in 1933, Franklin Roosevelt is elected president. He develops an omnibus law enforcement bill which places the Bureau of Investigation not just doing what you and I call whitecollar crime, because that’s largely what they were doing, but now puts them at the forefront of conventional criminal investigations nationwide. So now he’s developing a criminal law enforcement investigative organization. But now you have not heard me in the last five minutes talking to you about this one word about espionage. And that’s true. We weren’t focused on espionage. In 1934, the president ordered Hoover to begin to do, quote, intelligence investigations to determine the fascist threat in the United States. And then in 1936, he orders Hoover to do an intelligence and intelligence investigations to determine the communist threat, but again, not espionage. It’s only in 1937 that Hoover has a case placed on his lap, which the Bureau handled terribly. Absolutely terribly. And as a result of that gross handling of the investigation, the Bureau had to learn very quickly how to do this kind of work.

Justin Black, Spycraft 101

Okay, was that the Rumrich case that is mentioned in chapter one of the book?

Ray Batvinis

Yes, that’s exactly right. It’s the Rumrich case. And the case was handled by an investigator by the name of Leon Tero. And Tero was an excellent investigator. He was an outstanding investigator. But the one thing he had no experience on was counterintelligence and counterespionage. So as a result, he developed a lot of subjects, individuals who were clearly spying, but he handled it in a very conventional, investigative way. He gave them subpoenas to appear to grand jury. And of course, when the day of the grand jury occurred, they had all disappeared. They had all hopped on ships and fled back to Germany. So it was a huge black eye for Hoover. And Hoover was in one of those positions where I think every man and woman has ever been in. And he said, look, it says a prayer to God. If you can get me out of this, I’ll never do anything. I don’t know if he said that, but I suspect he probably thought it. But that’s when you begin to see him learning, and that’s when you begin to see the organization, the organization changing. That was sort of like the big bang moment for the Bureau of Investigation, which was now the Federal Bureau of Investigation.

Justin Black, Spycraft 101

Right, yeah. It sometimes takes a catalyst like that to create some real change, I guess. And sometimes the lessons that you take to heart the most are the ones that you learn the hard way, unfortunately.

Ray Batvinis

That’s right. And the military learned it as well, and the State Department learned it. The military was stunned by Rumrich’s confessions and by his statements. In fact, they suddenly learned that the Germans and probably the Japanese have penetrated most of the companies in the United States which were doing what would be considered today classified projects for the government. New technologies on weaponry, new technologies on ships, new technologies on aircraft. In the early 30s, if you came over from Germany or you came over from anywhere, for that matter, from Europe and you were a talented tool and die man, for example, if you showed up on time and you did your work, you got the job. There was no thought at all to a background investigation, no thought at all to polygraph investigation, nothing like this. This all begins to change after the Rumrich case.

Justin Black, Spycraft 101

Yeah, it changed quickly, obviously. And I have to admit that having looked at so many different subjects over the past couple of years, the US being kind of caught on the back foot by our adversaries is a pretty common occurrence across many different eras and many different organizations, unfortunately. But were they successful then, in your opinion, and catching up pretty quickly? I mean, did the FBI kind of change to meet this new threat, or did they have to go through, like, an extended period of growing pains even after this happened?

Ray Batvinis

No, this occurred figuratively. This occurred overnight. The State Department controlled counterintelligence in the United States at that time. When the Rumrich case came to a conclusion in December of 1938, he had a strong ally. Frank…oh, my goodness. I thought I’d never forget, it’ll come to me. The attorney general of the United States was a staunch ally of Hoover and Hoover and the attorney general of the United States fought very vigorously in the spring of 1939 or control of counterintelligence. Up until then, if you were the Secretary of State and there was a spy case in the State Department, the State Department would decide whether or not they’re going to handle it or not. If it was in the Department of the Interior, same thing. Department of the Treasury, same thing. Hoover and the Attorney General said, they can’t do it that way. You can’t have it fragmented and be effective. So they fought a vicious battle, bureaucratic battle with State and other agencies. Well, finally, in June of 1939, they went to the President of the United States, Franklin Roosevelt. And Roosevelt had to issue what we would call today an executive order. And Hoover ordered all of his cabinet members to refer any allegations of espionage, sabotage, subversion, Fifth Column activity, any allegation, any hint had to be referred to the Federal Bureau of Investigation for investigation.

It was essentially called the Clearing House at that time. And that was the big bang moment for the FBI to take over control of counterintelligence in the United States. And in very rapid succession, he formed what was called the Interdepartmental Intelligence Conference. Now, the interdepartmental intelligence conference was a gathering of the FBI, the military intelligence division of the War Department and the Office of Naval Intelligence of the Department of the Navy. And they would meet once a week, once every two weeks. And I argue that is the moment, that group is the start of what you and I call the Intelligence Community today. And it has grown to what we see today. And then at the same time this is in June, July of 1939 he orders all of his seniors back to Washington to begin to take classes in counterintelligence and counterespionage. And then at the same time, he also takes control of the Bureau’s destiny with regard to legal attaches. He sends an FBI agent to Ottawa, Canada, working in the embassy. And then he also starts what’s called the Plant Protection Program. And the Plant Protection Program was a program in which agents would be trained to go into factories and examine the factory top to bottom.

It would be a combination of doing background investigations on the employees, running their name against indices indexes that the Bureau kept on fascist groups and communist groups and going so far as to look at the lighting of the place, the safety of the place. Eventually, that was turned over to the military as the war started. And then finally, in 1939, what does he reopen to some criticism, but he reopened it–the General Intelligence Division that was closed in 1920. And that General Intelligence Division is still in operation today. Today. It’s called the National Security Division of the FBI.

Justin Black, Spycraft 101

Interesting. So the organization, as you said, it had to change overnight. And it took on a very aggressive posture across a lot of different fronts, obviously. Did he have any I mean, did he have to rely on some extremely talented people within the ranks, or were they just kind of building on I mean, were they just kind of making things up, essentially, or were they building on what the State Department had been doing or what exactly?

Ray Batvinis

Well, no, what they did was you’re absolutely right when he said he had talented people. He had very, very talented people. He had people like Shivers. He had people like Hugh Clay, who had been with him for a very long time. He was the head of their training unit, a very, very highly intelligent man. And another fellow by the name of Earl Connolly. And Earl Connolly was at the cutting edge of every major case that the Bureau had from 1925 up until 1951. Of them was Dean Milton Ladd. And Ladd was actually the son of a US. Senator who died in 1939 while he was still in office. And another one by the name of Edward Tamm. Ed Tamm was a summa cum laude graduate in law from Georgetown University in 1932. And he, in a matter of about five or six or seven years, became the number three man in the FBI under . . . It was Hoover, and it was Clyde Tolson. And then it was Ed Tamm. And Tamm ran the day to day operations nationwide, investigative operations. And then in the late 40s, just as an aside, Tam was selected by President Truman as a judge on the US Circuit Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia. So he had extremely talented men and women. And I mean, some women. They weren’t agents, but they were very, very talented. And you’re absolutely right when you talk about an aggressive posture. Hoover took a very aggressive posture when it came to what they called counterespionage. Counterintelligence wasn’t a term in vogue at that point, but counterespionage was, or counter spying was. That was sort of the term of art. They were still trying at the same time to come together with their terminology at this time.

Justin Black, Spycraft 101

So he obviously had to put all of these new procedures in place and create a brand new organization practically out of scratch. But as I understand it, he was also a very big proponent of cutting edge investigative techniques, wasn’t he?

Ray Batvinis

By all means. Hoover had developed the FBI laboratory in the early 30s. That was another individual who I met, Charles Appelle. He was a documents examiner. And it was Charlie Appelle who developed the FBI laboratory, also developed the idea of course, it was not a new idea, but he applied it very vigorously. The idea of fingerprint and having fingerprint cards and having people fingerprinted. If you were to start a job if you were to start a job with a defense contractor, you would immediately be fingerprinted, and a copy would go to the FBI. So he was using and we can talk about this in a few moments, too, as we go on. He was using cutting edge technology anywhere he could find it in any way he could find it, absolutely.

Justin Black, Spycraft 101

Yeah. That’s fascinating to me. Where does that kind of thing even come from at that stage? I mean, where would you seek out brand new ways of uncovering evidence or of investigating a crime where these things coming out of, like college laboratories or techniques that were other country law enforcement agencies were already using? Or something else?

Ray Batvinis

All of the above. I found in my research syllabus that he used. And you would see there were a number of college professors who were doing work in what you and I would call forensic science. And he began to pull this together. And I don’t want to get into it because I know I’m only confused because it’s been a while since I thought about it. But he used universities. He sent one agent, a fellow by the name of Maurice Acre. In the late 30s, he sent him to London to attend the Metropolitan Police Department senior officers course on how to conduct investigations overseas. He had been working very closely throughout the 30s under the radar on counterintelligence or counterespionage cases with Stewart Wood, who was the head of the RCMP in Canada. And I say under the radar because he had to do it without the knowledge of the State Department because they didn’t want the police interfering in foreign diplomatic matters. So he actually had to work under the radar with Stewart Wood anywhere he could find someone credible or the Bureau could find someone credible who had something positive to offer. It’s safe to say that he would reach out to that person and have them come in and begin to train our personnel.

Justin Black, Spycraft 101

Wow. That must have been a godsend. Did all of these techniques and all of this work did this lead to them kind of gaining an effective hold over the foreign intelligence activities inside the United States? Or is there just so much going on that they were kind of fighting the tides the entire time?

Ray Batvinis

No, it proved to be very, very valuable. Not only this sort of cost disciplines, these new techniques and these new methodologies and these new technologies were directly applicable to criminal investigations as well. One of the new technologies that Hoover developed and I’m not completely conversant with this was photography. The Bureau developed a new and sophisticated message of surveillance photography. When you read my book, the book about the Duquesne case that’s where it all kind of came together. All of this effort came together in terms of new technologies with new photographic techniques that weren’t available in other countries. So the Bureau was a forerunner at this. The Bureau was also a forerunner when it came to what we take for granted today car radios. In other words, communication from car to car that was completely alien in the early thirties. And they began to develop that kind of technology as well. And they began to develop new technology when it came to telephone intercept. Wiretapping was still in its infancy at that time. And trying to develop wiretapping on a subject when there is no legal basis for it, before we even had laws connected with that, before you could even work in cooperation with the local phone company, they had to do this. So this was the Wild West that they were dealing with at this time.

Justin Black, Spycraft 101

Yeah, it certainly sounds like it. I mean, they were jumping in at just a time of technological revolution and enemies arriving from overseas all the time. I mean, like these networks that we talked about, like the Duquesne network. And I’m glad you mentioned that because in some ways that brings us full circle. The very first episode of this podcast was about Fritz Duquesne. And so he lived quite a life, but we of course, talk quite a bit about his spirit that operated here in the United States leading up to and during World War Two. A little bit, but do I recall correctly, since you mentioned the photographic techniques, were some of the most famous photos taken of him? And I guess it was that guy Sebold, like they were taken through a one way mirror while they were meeting or something like that. Is that correct?

Ray Batvinis

Yes, that’s right. That’s exactly right. They were taken through and then they knew that they were taking these photographs. And it wasn’t just photographs. We’re talking about video. In other words, not snapshots. These were e developed to the bureau developed the methodologies through a one way mirror to take video. And of course, when that is shown to a jury who had never seen video before, real video, they may have seen movies in the theater when they see video like that. It was very powerful when it came to the prosecution’s case.

And the other thing that they did, which I thought was very clever, they were not allowed to record conversations. In other words, you and I think today, okay, we’ll put a microphone, we’ll get a judge to give us a warrant and get a warrant and we’ll put a microphone in the room and the microphone will record the conversations. Well, there was a case called the Nardone case, and the Nardone case essentially prohibited recording conversations unless both parties were aware that the conversations were being recorded. So what they did at the same time that the video was being recorded through the one way mirror, an FBI agent by the name of William Friedman, there were probably others, but he’s probably among the most famous.

He testified at the trial. He’s listening through the wall and the wall, the Bureau designed the wall of the office so thin that you could easily hear the conversations without any type of technical enhancement. But what he’s doing, he’s listening to. The conversations and he took shorthand. So he’s shorthanding the conversations back and forth and then he converts that into a transcript. He testifies that I was there when that video was recorded and this is what they were saying.

Justin Black, Spycraft 101

That’s quite a workaround there. That’s fascinating.

Ray Batvinis

Yeah. And that’s how they then my other point is the technology in terms of coming to grips with new challenges. When they were transmitting and receiving information from the house in Centreport, Long Island they were confronted with major issues that they had never been confronted with. The most obvious is feed material. The Germans are in contact with the person they think they think is the Sebold. And they’re saying, well, we need this and we need that and we need this. And now the government, the Department of the Army or War Department or the Navy Department confronted with the fact that, holy cow, they know this stuff. How are we going to give them secrets which we want to keep and keep the case running? So they had problems with that. And then of course, what else do they want? They want to know when and where ship convoys are forming up and when ships are leaving the Brooklyn Navy Yard. The Brooklyn Navy Yard at the time and would become even larger. But during the war, the Brooklyn Navy Yard was the largest Navy yard in the world. They were shipping ships are going out of there to Africa in Europe and into the Pacific and they wanted to know when the ships were going out.

So in point of fact, what they would do is now they’re confronted with this type of thing, how do you get feed material? They never had this problem before. And then what they would have to do is say, okay, well, the USS Manhattan just left Brooklyn and it’s bound for Great Britain. It’s going from here to here. And then what they would have to do is notify the Manhattan Ussman take a different route. Okay. So you can avoid the submarine wolf packs along the way. So it was a really big deal and it was a very, very complicated multiagency endeavors, so to speak. It wasn’t just the Bureau. So the Bureau at that time starts with the Duquesne case and the case starts, what I refer to when I lecture, as tactical deception. They’re deceiving the enemy on a tactical level, not a strategic level yet that will come later on in the war. But on a tactical level they’re deceiving the enemy and the enemy fortunately bought it hook, line and sinker.

Justin Black, Spycraft 101

Well, that’s a major success for them and it’s still a relatively young organization at that point. But I guess like you mentioned, that they just learned a lot very quickly, especially with Hoover at the helm there.

Ray Batvinis

Yeah. And Hoover was very fortunate. Hoover ran the organization, but Hoover did not run these investigations. I would take on anybody who said that Hoover ran these investigations, and he did not run these investigations. Hoover sat at the top running the organization and dealing with other agencies of the government. But the day to day, nitty gritty work of the organization was run by Tamm. He ran the day to day organizations, and his assistant directors ran the organization, ran the operation investigation. Let’s put it that way.

Justin Black, Spycraft 101

Yeah, that might have been the best, from what I understand. We’ll talk about Hoover a little bit more soon, but I’m quite a divisive guy in some ways. We’ve been singing this praises so far, but that wasn’t all to him, his character, I don’t think.

Ray Batvinis

Yeah, exactly.

Justin Black, Spycraft 101

I do want to ask you, the book is just filled to the brim with case after case, so I know that we can’t go through all of them by any means. But there is one person I want to talk about, I’ve been wanting to talk about on the podcast for quite some time. That’s Walter Krivitsky, the Soviet defector. Can you talk about the Bureau’s interaction with Krivitsky?

Ray Batvinis

Yeah, I think the Bureau did a I don’t think, based on my work, the Bureau did a very poor job with Krivitsky, and they didn’t understand Krivitsky. They had had no experience with an NKVD officer, senior officer. And I think it was complicated. And I’m going out a little bit on a limb here. I don’t think they had the best interviewer handling him, so to speak. They didn’t have someone they didn’t have someone who had a depth of experience to begin to probe somebody like him, nor did they understand the complexity of the experience of someone like Krivitzky, who was let’s face it, he was a defector, and the complicated mental, emotional, and psychological baggage that he brought with him. And it would seem to me that had they had the experience and knowledge and you only accrue this over a period of time I’m not defending anybody. I’m just putting it into context. Today we deal with defectors much differently than we dealt with at that time. At that time, there was no mechanism for the government accepting defectors. Today, the CIA handles defectors, and they have a very professional process by which they do this.

They have psychologists involved in, psychiatrists involved, and people who are very skilled at resettlements and dealing with families. None of this existed at this time. And the proof was in the pudding because later on and of course, the other thing was he was under the care of Ivan, which Isaac Don Levine, who was a journalist. It was a journalist who actually was kind of taking care of him. And then eventually what happened was the British learned about him and he went to Great Britain, and he provided the British with some very good information. One of them, I think, was John King. I think his first name was John. And John King. He reported on John King. And John King was a communicator. He was in the Foreign Office who had been recruited by the NKVD. So the Bureau was not a high watermark for the Bureau at the time, and you’ve got to call them out on it. So that’s my take on it.

Justin Black, Spycraft 101

Yeah, that is. One thing that surprised me a little bit from your book was that you don’t shy away from criticizing missteps and miscalculations and that sort of thing, including all the way to the last page, really, of the book. So it seems like a pretty objective look at what the bureau accomplished and failed to accomplish over the years. But, Ray, if you don’t mind, can you tell for the people that are not really familiar with Krivitsky already, what was his motivations for defecting in the first place? I know, like you said, he was an NKVD agent working under Stalin, and he came over prior to World War II. But can you kind of expand a little bit on that for the listeners?

Ray Batvinis

Yeah, I’d have to go back and refresh my memory, but basically he was an NKVD, basically a Soviet intelligence officer in the 1930s, and he was extremely talented, and he ran NKVD operations in Western Europe in the 1930s. There’s a debate was he a colonel? Was he a general? Who knows? But he was part of their foreign directorate, their foreign apparatus for collecting intelligence. His job was to go out and recruit sources, and he was very effective at it. What happened was he, like probably hundreds of others, will never know. Maybe thousands of highly competent guild intelligence officers came under suspicion by Stalin. This is what we refer to today as the purge. And they started being called back for consultation, and they would get a letter saying, come back to Moscow, and they come back to Moscow. They’d be immediately arrested, and it be a quick show trial, and a bullet would be put in the back of the back of their head. Well, they knew the rumors were floating around that this was what was happening. And then what happened was one of his closest friends, a very important NKVD officer, Ignas Reiss R-E-I-S-S got his letter to come back, and he refused to come back.

And his body was found along the side of a road shot multiple times in Lausanne, Switzerland. That was the message for Krivitzky. Krivitzky fled. He had been putting money away, slowly putting money away in an account in Paris. And then when he found out about Reiss I think I mentioned very close to one of his closest friends, that caused Grovitzky to flee, and then he came to the United States, and then he came under the umbrella of Levine, who was an anticommunist journalist, and began to use Krivitsky for his sources. For many of his articles, he wasn’t the only one who fled. One of the very famous ones, including as well as Krivitsky, was Alexander Orlov and Orlov was a very senior NKVD officer who was running Soviet operations in Spain during the Spanish Civil War. What he did was he changed his name, and he came into the United States and alias and basically burrowed his way into American society. And it was only about 1617 years later, in the early 50s, that he surfaced in Cleveland, Ohio. And it’s really quite a remarkable story. But those stories are really quite remarkable.

Justin Black, Spycraft 101

Yeah, they certainly are. And I haven’t spent as much time reading about some of those events in the 1930s as I would like to. And it’s obviously you have a really good handle on all of that from all of your research. But some really amazing stuff was happening, and we were kind of struggling to catch up with events at that time, it seems. So Krivitzky comes over, and he is very public. I think he goes in front of Congress, doesn’t he? And I know he writes a book, he writes an autobiography about his time in Soviet intelligence. And then you mentioned that he was somehow kind of mishandled by the Bureau.

Ray Batvinis

Yeah, I looked at his file. Unless his file is incomplete and I don’t handle it, what I have certainly suggests that they mishandled them. They didn’t understand it. They had no grasp of the concept of the defector. Now, that will change later. That’s interesting, too, because are you familiar with Victor Kravchenko, the name?

Justin Black, Spycraft 101

I can’t think of anything about him at the moment, but I’ve certainly heard that name.

Ray Batvinis

Kravchenko, for example, Kravchenko worked in Washington, DC. And he was an official with the Purchasing Commission. What you and I know is lend lease. And he defected. And there were because Russia was our ally, there were voices in our government said, well, let’s send him back. And the Bureau and the War Department lined up, said, no, you’re not sending him back at all because he wasn’t an intelligence officer. But he provided information. But the Bureau at that time, when I was in the Bureau during the Cold War, we actively tried to recruit intelligence officers and we tried to recruit foreign diplomats, and we were successful at it. But at this time, we were just putting our toe in the water. The idea of an FBI agent undercover contacting an intelligence officer, that was alien at the time. But they stood up and Kravchenko remained in the United States and had a fairly successful life is the best I can remember. But at that time with Krivitsky, it was a very different situation altogether. But we clearly mishandled it.

Justin Black, Spycraft 101

So what ended up happening to Krivitsky in the end?

Ray Batvinis

Well, Krivitzky, depending on what day it is and who you talk to, did he commit suicide or was he murdered in a wet operation by the Russians? We don’t know. He was found in a hotel room with a bullet in his head, and the hotel was right near Union Station and Capitol in Washington, DC. The official finding was that it was a suicide. From what I remember having read, he actually bought a weapon in Virginia and the weapon was with him, I believe, at the time when the body was discovered. And the bullet, I believe, came back and matched that weapon. But his door was locked. They had to break their way into the hotel room. So the eternal question is, was this a wet affair on the part of Soviet assassins who managed to do such a great job that they made it appear like it was a suicide? Or did Krivitzky commit suicide? It wouldn’t surprise me that Krivitzky committed suicide, and I’m not saying you did. I’m not saying what happened because of the pressures that these people are under. I mean, it is excruciating the pressures that they are under once they make that decision to go.

Justin Black, Spycraft 101

Before we go on, I want to let you all know about a new educational tool you’re not going to want to miss. It’s the Gray Man Briefing Classified. By now, I think I know my listeners pretty well, and take it from me, this briefing is exactly the news and educational reference source that you’ve been looking for. You’ll get breaking news updates from all over the world on topics including planned protests and riots, low intensity conflicts, natural disaster alerts, cyberattacks supply chain disruptions, and more. You’ll also get access to articles that help you build your own skills, including urban survival, home security, counter surveillance, escape innovation techniques, and more. And this is much more than just a newsletter in your inbox joining the Grey Man Briefing Classified also includes invitation only channels on the telegram and signal apps for convenient real time updates. The newsletter subscription is normally $5 per month, but if you use the code GBC SpyCraft, you can save 20% each month for the life of your subscription. I’m already a member myself and have been reading and learning a lot since I first subscribed. Look it up yourself. At Greyman briefing.com. That’s gray with an a gray man briefing.com. And use the discount code GBC Spycraft to save 20% right from the start.

Ray Batvinis

And remember that they leave family behind. And by leaving family behind, that family can pretty much expect that they’re going to be eliminated as well. So there may have been profound guilt, I don’t know.

Justin Black, Spycraft 101

Right. You can totally see both ways and it’s easy to say, oh, well, he was killed, obviously. But it’s also when you really try to put yourself in his shoes, see how the pressure can build up to be too much. You’ll probably never see any of your relatives ever again. You’ll never go back to your homeland ever again and live to talk about it anyway, unless you’re kidnapped by them and taken back for a show trial or something like that. And he has no one. He’s left everything behind and he’s sitting there alone in a hotel room waiting for one of the mobile groups from the NKVD to catch up with him or something like that. So under those circumstances, you can see how he might want to kind of permanently put it into that pressure. But we also know about those groups traveling around and killing people and their very, very long history of killing people and making it look like a suicide or making it look like an accident or an undetectable poison. So could totally be either one of those things. Honestly, it’s a really, really interesting case.

Ray Batvinis

Yeah. And it’s interesting what I find interesting also is that over the years, to my recollection, maybe you know better than me on this, that no one has ever come out and said, to my knowledge, either way, we’re coming on almost my goodness, we’re coming almost on 80 or 90 years. There was nothing in the Mitrokhin archives, I’ve heard nothing from defectors who have gone back and look at the records. It’s entirely possible that Stalin was a surprise, as everybody else to learn of Krivitsky’s death. Right.

Justin Black, Spycraft 101

Must have made his day anyway, if that was a surprise.

Ray Batvinis

Exactly right. One for us. Right.

Justin Black, Spycraft 101

Yup. It’s one of the many, many loose ends of that period of history that will probably never get a satisfactory answer on that’s.

Ray Batvinis

Exactly right. Exactly right.

Justin Black, Spycraft 101

And I swear, a lot of times I hate to go off on a tangent, really, but a lot of times you get an answer and then you have to wonder what is that intentional disinformation or is that someone taking credit for something that they didn’t do, or what?

Ray Batvinis

Yes.

Justin Black, Spycraft 101

But nevertheless, yeah, it’s a fascinating story, and I would love to know more about that case, but if it hasn’t come out in the past 80 years, I kind of doubt that it’s going to come out in the next twelve months or so. I’d like some immediate gratification on that, but I don’t think it’s going to happen.

Ray Batvinis

I agree with you.

Justin Black, Spycraft 101

So kind of going into switching gears a little bit, moving into the actual war, because you mentioned Pearl Harbor earlier, but once the US. Got involved in the war, how did the FBI contribute to the overall war effort as a state side law enforcement agency?

Ray Batvinis

Well, you know, one of the first questions when we started was anything new that I found. This is not in my book that we’re referring to, and I don’t want to be unfair, but when it came to I end my first book at Pearl Harbor, and I argue that the Bureau wasn’t aware of it at the time, but with the end of the Duquesne case, the back of German espionage was broken. The Germans never had an ability to reconstitute a network of agents here in the United States following Pearl Harbor. They never had an effective stay behind group. But what happened was, and I found this can I just talk about a little bit about this aspect of the second book.

Justin Black, Spycraft 101

Yeah, I forget I’ve read a lot of your stuff, a lot more than just what’s in this book. So I kind of forgot where it left off at, honestly. But it’s all fascinating.

Ray Batvinis

Well, if you remember if you remember with the radio station in Central Port yeah. That shut down around July or August of 1941, and it shut down, but they made the arrest. They kept it going for a couple more weeks to see if they communicated, but they shut it down. Well, what happened was, at that time, the Bureau had about five or six double agents having nothing to do with the Ducat case. And they were percolating along. And in July or August of 1941, an Argentine businessman by the name of Jorge Mascara arrives at the US. Consulate in Montevideo, Uruguay. Now, I won’t go into the background because it’s too involved, but he was a businessman. He was an Argentine businessman in Germany who wanted to leave Germany. Germany was not allowed to leave until he agreed to cooperate. And he left all of his money behind. So he agreed to cooperate basically to get out. He goes to a multi bideo Uruguay, which, you know, is just not very far from Buenos Aires. He walks into the US. Consulate and he says, I was sent out by the Germans, and I’d be willing to help you.

So the consulate contacted Edward Tamm. And Tamm, in a nanosecond, said, Send him up here. We’ll pay his rate up here. So he came up and he sat down around September, October, again with my friend William Friedman, who spoke German. He was a German. He spoke fluent German, and he was a farmer from Oklahoma. How do you believe that one? Right? But he comes from a German family in Oklahoma. He sat down with him, and he told him about the fact that his job was to set up a radio station to try to get to America and set up a radio station. But what the Bureau then did is they went even further out on Long Island. And for you to really understand Long Island, New York at that time, I always urge people, you don’t have to read the whole book, although it’s a wonderful book. It’s on modern library’s top 100 books of biographies of the 20th century. What’s called the power broker by Robert Carroll. And before the war, for a person to go from Manhattan out onto the island is like going to Mars. Okay? Because all of the plutocrats on the fabulously wealthy who own the States out there, and the farmers didn’t want riffraff coming out there, so they made it impossible to get there, which made it ideal for the Bureau.

What they did was they went out probably about another 30 or 40 miles beyond centerport to Wading River, New York. Wading River is a postage stamp. It’s just a crossroads but it’s right on the it’s right on the north shore of Long Island overlooking Long Island Sound. The property out there is beautiful today. And the bureau got a place called the Owen Farm, and the house on it was called the Benson House. And beginning in January of 1042, they transmitted double agent messages, messages filled with misdirection, complete falsehoods to the Germans in Hamburg. And the Germans believe the whole thing. Now, what was the value? It ran from January of 1942 until around June of 1945. If you remember, the British and the Allies came in, and the war ended on May 8, 1945. But the Bureau was ordered to keep the radio operating because there was great fear on a part of the Allies that Hitler would flee to Bavaria his readout at Berkdas Garden and run a guerrilla war. Well, as it turns out, we know that didn’t happen. So the radio was shut down in June of 1945. But what it did was it supported.

This is one of the things I’m very proud of, finding this the Bureau and I don’t think the Bureau was even aware of this. Our Bureau historians today are even aware of it on their own. Is the fact that the bureau played a role an important role, yes. Pivotal role, no. But a role in Operation Fortitude. And we know that Operation Fortitude is what? The deception campaign in the run up to the Normandy invasion. It played a role in the Normandy invasion. It played a role in Operation Bluebird. Operation Bluebird was the operation commanded by Admiral Nimitz for the invasion of the Marshall Islands to confuse the Germans and to confuse the Japanese into believing that the attack would come through the Curial Islands. And it also played a role, I believe, in convincing the President of the United States to pursue the atomic bomb. It was a very, very big deal. It really was. Right now, if you have listeners who live on Long Island, they can go to Wading River. The house is still there. It’s located at a place called Camp Dwolf, and Camp Duolf is a retreat facility for young children and people who are just getting away for a retreat and conferences.

And it’s in Wading River, New York, and it’s owned and operated by the long island of the Long Island Episcopal Diocese. But you can go there and see the plaque that we put up on the side of the building and get a sense of what it was like there at that particular time. But now, I mentioned to you earlier that the decaying case was a classic example of tactical deception. The Benson House or the Benson house operation in Wading River? Classic case of strategic deception. You get my point?

Justin Black, Spycraft 101

Absolutely, yeah. That’s fascinating. I shared a video clip a little while back on Instagram because I have a lot of people that follow stories there. And you’re in that documentary, I’ve seen the video of you standing at the Benson house and down in the basement where the Buick engine was and everything, honestly, and a lot of people have seen that since I shared it. So are you saying then that you can go up and visit the house? Are there, like, tours available or anything like that?.

Ray Batvinis

I’m very proud of the fact that they are very receptive up there. The gentleman up there, Father Matt Tease, he’s recently ordained the Anglican priest, and he runs the facility. We did the ceremony up there putting the plaque up in June 9 of 2014 to commemorate the 70th anniversary of the Normandy invasion. Well, since then, Matt contacted me and said, we’d like to see if we can get the house on the New York State. I’m trying to think of New York State list of historic places. So I work that, and we put the radio station on it’s on the New York State list of Historic Places. And as a result of that, the federal government has placed it on the National Trust. It’s on the National Trust. And I’m sure I’m using a long terminology, but the National List of Historic Places. So we’re very proud of it, and people can go up there. As I said, we just had a ceremony. I won’t go into detail on it, but we’re learning more and more about this facility all the time. And a week ago, we had a ceremony up at the diocese headquarters in Garden City with regard to this. But people will go up there. They’re very receptive. You can see photographs up there. They may even take you down into the basement to see the block of cement that is still there. They give out brochures. It’s now on the Long Island History Tour. So, yeah, it’s a pretty big deal.

Justin Black, Spycraft 101

Justin okay, that’s fantastic. I’ve had it bookmarked on my map for a while now, just in case I’m in the area, but I haven’t made it out that far onto Long Island recently. But it’s a beautiful house, and it’s a beautiful spot, regardless of the actual intelligence history there. But I would certainly love to go and walk around inside the house and hear it from the diocese there as well. So hopefully I get a chance to do that one day.

Ray Batvinis

Yeah. If you stand in the back, you have literally a 180 degree view of Long Island Sound and Connecticut, which is 18 miles across Long Island Sound. And on a clear day, if you’re lucky, you can see submarines coming into New London, Connecticut. That’s how breathtaking the site is. It really is a gorgeous piece of property.

Justin Black, Spycraft 101

Yes, I’ve got to see it now, definitely. I’ll definitely make time to go there sometime soon. So I do want to ask you and just switch gears again just a little bit. We talked quite a bit about Hoover at the beginning of this interview, but we talked a lot about the positive changes that he made to the Bureau, but he’s got a very I guess I’d call it a checkered perspective. People have a lot of criticisms of him as well, and I don’t know how well informed those criticisms are, but I would love to hear it from you. What kind of legacy did Hoover leave the Bureau with in the end? Like, how is he viewed within the Bureau, even to these days, as such a tremendously influential leader?

Ray Batvinis

Yeah. I consider him and I say this unabashedly I consider him a great man. He was a man with feet of clay. No question about that. He was very flinty. He was very, very thin skinned, and he was very, very autocratic. And I worked for a gentleman by the name of Cartha DeLoach, and when you get off, you can look him up. His name is Deke DeLoach, and Deke was one of his senior senior officials in the in the on into the very important guy. And I knew Deke very, very well in later life. He later, when he retired, he became an executive with Coca Cola, passed away a few years ago. But he called Hoover the best tap dancer in Washington, and that’s exactly what he was. He knew where all the skeletons were buried, and he was a Washingtonian to the core. He was born and raised in Washington. And I think within the Bureau I can’t really speak for that other than to say it seems like they regard the legacy that he created, but they are also operating a little bit on tinder hooks because of the controversies that swirled about him later on.

I also find it interesting that here you have this giant of 20th century, and it’s interesting that a good biography has yet to be written about him. A good biography has not been written on him. Biography, first of all, has not been written on him probably in the last 25 years. And I’ve been in touch with some authors who I think are struggling with his legacy because I don’t want to get down into the weeds, but the more in this post Cold War era, I mean, there are people now who are 25 and 30 years old who don’t even remember the Cold War. And in this post Cold War era, there are a lot of confusion now. A lot of what they vilified Hoover for shortly after his death, the long knives came out after his death and went after him. But now a lot of stuff is coming out of the former Soviet Union that says, whoa, we were penetrated. Issues like Venona. You’re familiar with Venona?

Justin Black, Spycraft 101

I’m quite sure, yes.

Ray Batvinis

Transcripts the Vasilliev Notebooks what’s coming out about Vasilliev the Information the Freedom of Information Act, which was passed in the early 70s, has produced a huge body of literature regarding Soviet activities. The story of Operation Solo and what we learned from the Morris and Jack Childs and other sources puts Hoover in a much more complicated and complex view, so to speak. My biggest complaint about him was he stayed too long. It happened. But he was one of these individuals who just stayed too long. And he never wrote a memoir. There just hasn’t been a good biography of him, a good scholarly biography of him to put him in the context of the 20th century. The reality is he built the most important law enforcement organization in the world, and that’s his legacy.

Justin Black, Spycraft 101

Yeah, certainly his name is fully intertwined with the FBI. I would say that people that know nothing else about the FBI could probably say that J. Edgar Hooever was the first major director for the organization, even knowing hardly anything else because of how closely his name is aligned with the FBI. You mentioned that there hasn’t been a good biography. So I’m looking over my shoulder right now on my bookshelves, and I’ve got two biographies of his. I haven’t actually read either of them yet, though, because I always have more books than I have time to read, unfortunately. But one of them I noticed I’m looking at it right now, and the title of it is Puppet Master by Richard White. And quite frankly, that tells me that it’s not going to be a glowing portrayal of his program with the director, of course, but that doesn’t mean that it’s also full of inaccuracies, either.

Ray Batvinis

No, I’m not saying that at all.

Justin Black, Spycraft 101

He’s got a complex legacy, to say the least. But were there any issues? I think that you mentioned early on, the Bureau was kind of born out of this scandal with the original Bureau of Intelligence, the Bi, and the privacy violations that they were being accused of early on, out of a hallmark of his as well, right?

Ray Batvinis

Well, that’s right. That’s exactly right. And I think that’s part of the complexity of the issue. One of his curious weaknesses was the fact that he was number driven. For example, stolen cars is what immediately comes to mind. And he would go up to Capitol Hill, and we covered this many stolen cars, and he had a lot of supporters on Capitol Hill, and of course, you get his budget every year. But then the question was, was this really that important a priority, when in point of fact, maybe we should have been looking at organized crime a little sooner than we did, but then you have to sell. Well, wait a minute. The laws had yet to catch up with effective organized crime investigation. For example. We never really got a good effect of wiretap being authorization until the late 1960s. So it’s complicated. It’s all I’m saying. And clearly, he had his weaknesses. He was clearly a man with the feet of clay who really should have left earlier. He should have retired. But the reality is he had nothing. He was a bachelor. The bureau was his mistress. If he had retired, he probably would have died the next day because he would have had nothing to do. The Bureau was his whole life.

Justin Black, Spycraft 101

Yeah, there are a lot of fellows out there like that. I’m afraid, to a lesser extent, maybe they don’t leave the kind of intergenerational impact that he did. But, yeah, there’s a lot of people that they throw themselves into their work and never look back. Really? I’m curious, since you started with in 72 and he left where he passed away in 72. Did you meet him?

Ray Batvinis

No, he passed away on February 2, February third, and I entered on duty on July 17, and L. Patrick Gray was the director at the time, if you remember. L. Patrick Gray was embroiled in his own scandal, although we didn’t know it at the time with Watergate and what he was doing, in effect, with Watergate. I came in my class was unique in the Bureau because we had the first two women who became FBI agents in my class.

Justin Black, Spycraft 101

Oh, wow. Interesting. Were they classmates of yours? I mean, you knew them well?

Ray Batvinis

I didn’t know them well, no, because you’re there for 15 or 16 weeks, and you’re just trying to keep your head above water. We all are. And they went off to their offices. I never really saw them again. One was Sue Roley. And she was a former US. Marine, and the other one was Joanne Pierce, and she was a former Roman Catholic nun.

Justin Black, Spycraft 101

My goodness.

Ray Batvinis

Yeah. And Susan left, I think, after about eight or nine years, and Joanne retired. I don’t know what year she retired, but she retired. She married and retired. We didn’t recruit her out of the convent, as many people like to believe, but she actually had left the convent and was working for the Bureau, so she was a new hire. And the funny part about the whole thing was that we were the first class also to go through the new academy in Quantico. And that’s a whole story on its own because the Bureau had no policies, had not given one thought, as far as I can tell, to women becoming FBI agents. So the locker facilities that we had had no female locker rooms, all of these issues. Yeah. Anyway, I never met Hoover. I came in under the L. Patrick Gray regime and spent the next 25 years with them.

Justin Black, Spycraft 101

Wow. Fascinating. So I did a previous episode, just recorded it last month, and that episode was about the Pinkerton’s National Detective Agency. And during that time, I spoke with the guest, and he mentioned some possible similarities between Alan Pinkerton and J. Edgar Hoover, especially in terms of, like, managing the organizations image. So I’m curious. I don’t know how much you’ve studied about Allan Pinkerton, although I’m certain you’re familiar with it. But do you see any similarities there at all between Pinkerton, the previous century, and Hoover and the way that they kind of tried to care for the organization through thick and thin and grow that brand and grow that image?

Ray Batvinis

I know very little about Alan Pinkerton, except some stuff things I’ve read with regard to the Civil War and later the Pinkerton Detective Agency. But there’s no question in my mind about Hoover shaping the image of the FBI. I didn’t read them, but I had an opportunity one time to go through the file rooms at the National Archives out at College Park. And there are just boxes and boxes and boxes and boxes and rows and rows and rows and files and files of the FBI and essentially the media in 1930. If Hoover wasn’t a law enforcement officer and a lawyer, he would have been excellent on Madison Avenue. He had a certain skill in helping to shape the image of the Bureau and him as the leader of the Bureau. And this all begins during the 1930s with the G-Man as a counterbalance to the crime that’s spreading across the United States. Hoover was a real glamour boy. Hoover would be at the Stork Club in New York. He would be at the theater in New York. He’d be written up in the New York Times, the New York Journal American, the New York Herald Tribune in the Personalities section.

And this is where he begins to shape the image of the G-Man, the guy with the three piece suit and the snap rim hat carrying a Thompson submachine gun. And that’s who’s either a lawyer or an accountant. Yeah. So he had that skill, and he really promoted that to the organization’s betterment really in the long run.

Justin Black, Spycraft 101

Yes, I would say so. That’s a very indelible image. I mean, that’s exactly what you think of when you think of an FBI agent anytime before 1970 or something like that. I would imagine you kind of picture them in that traditional G-man role, which was totally intentional on his part, of course.

Ray Batvinis

Exactly. That’s exactly right. And that’s how he shaped it. How he shaped the seal of the FBI. Fidelity bravery integrity FBI. This is all part of his efforts to help shape that image.

Justin Black, Spycraft 101

Absolutely. Well. Ray. I have to ask you. I know this is definitely not in your book. Origins of FBI Counterintelligence. But because you personally worked on some of the big cases later on during the Cold War. I would love to ask you a little bit about your own involvement in the Ronald Pelton case. Because that one has come up a couple of times here on the podcast in the past.

Ray Batvinis

Yeah, I was blessed. The only way I can describe it, it was August 1 or so, 1985, and I was promoted from the ranks of regular street agent to supervisor of the Counterintelligence squad in Baltimore. And I said I wasn’t there no more than three or four days when the teletype came in, code named PASSERINE Passerine, and PASSERINE was the code name for the unknown subject at NSA. Vitaly Yurchenko KGB officer, Colonel Line, KR officer, identified as having walked into the Soviet Embassy in 1980, and they ran him for another three or four years. So that was my case. I was the supervisor of the case. And I think the most important decision I made, and I would swear to this to my dying day, the most important decision I made was selecting the two case agents to run it, because they were geniuses. They were excellent. They were the best of the best. You know how in your own life there are people you want to be with who give off positive energy and who are competent and skilled? That’s how I felt about these two guys. And my job was to just supervise the case, to oversee the case.

What happened was we had a very good special agent in charge, and I got called up to his office one day, and I went in, and there were two naval officers there, and I had to leave the room because I didn’t have the clearance for what they were about to tell him. But what they told him was that whoever it was, we didn’t know it was Pelton at the time. Gave up Ivy Bells. Are you familiar with Ivy Bells?

Justin Black, Spycraft 101

I haven’t talked about it here on the podcast before, but it’s a famous operation, certainly.

Ray Batvinis

Right. Well, he gave up Ivy Bells, so that’s later on, of course, I did find out. But what my boss did was he said, we’re not going to run this like a conventional case. So he called me in, and we’re a group of us, he called, we want the best agents in the office on this case. And you never get that. You always have 300 hitters. You have 250 hitters, 220 hitters, but we had all 300 hitters. And we sat there for an hour and a half, and we cherry picked all the best agents from the different squads in the office. And they were about and I’m guessing here because it’s been a while since I’ve thought about it, maybe eight or nine or ten. And my job wasn’t directing them. I found it when I reflect back on it, my job was to hold them back. You know what I mean? In other words, this was a single mission concept, and everybody knew the stakes involved in this thing. So my job was, let’s do this, okay? Let’s do it. Let’s think it through. Let’s walk ourselves through it. And then we had an SAC, who was a wonderful SAC God rest his soul, great.

But he had this notion that we could talk to his wife. And that was always dangerous because we were in the covert phase of the investigation. The first time this case burst into the open was the day that we invited him to sit down with us on November 24 in Annapolis, Maryland, at the Hilton Hotel. So we were in the covert place. We couldn’t talk to her because they were estranged, but we couldn’t talk to her for fear that she would go back to him and tell him this. So I’m trying to convince my boss that she probably doesn’t know anything. She probably knows nothing about it. Even though Barbara Walker knew a lot, she couldn’t make the case for us because of the nature of an espionage. We can do another podcast and talk about that if you wish, sometimes, but the nature of an espionage case is such that the wife isn’t going to be able to do it. Well, he was insistent. What I did was I knew a fellow by the name of Harry Roberts, and Harry was in the Rochester, New York, resident Agency, and Harry had the ticket, had the investigation on Joseph Helmich.

Are you familiar with Helmich?

Justin Black, Spycraft 101

No, I don’t think so. Okay.

Ray Batvinis

Well, Joe Helmich was a spy who spied in the 1960s while in the army. In the army. Not because the army didn’t have good people, just couldn’t make the case because of the issue of a large part of it has the issue of the Miranda warnings. Okay, we can talk about this some other time. So Harry basically sat down with Joe Helmich in a motel room for over three months. Not every day, every other couple of days. And Harry began to get his confidence, and Harry began to allow Joe to loosen up. But after a while, Joe was telling him everything about it, telling them everything about the case, about what happened here, what happened there. And then, of course, our job after that, or the Bureau’s job, was go out and try to corroborate as much as we possibly could. The bottom line here is that based on Harry’s interviews of Joe Helmich was sentenced to life in prison, in federal prison for espionage. Now, it was Harry because the SAC was our boss, and he was not going to take our word for it. Harry was going to leave the next day, so he didn’t have to worry about having to put up with our boss.

And Harry basically said no. He said, it’s not going to work. You’ve got to sit down with him, and you’ve got to interview him, and you got to get a confession from him. So Harry went back, and the boss I always think about this. I think my boss called me up, Ray, you’re right. He said, we have to sit down. And so everything that we did in that particular case was geared toward a moment when we’re going to have to sit down and interview him. And the way the agents did it was brilliant. It really was. They rehearsed it and rehearsed it. We had role players playing Pelton’s role of someone who came up with this wrinkle or that wrinkle. So they were always ready for a possibility of what he was going to say. And then what they did was they sat him down and they didn’t have to read him as Miranda Rights, they called him. He was across the street and he was across the river in Eastport. They would like to talk to you. They were dressed down. They were very, very casually dressed. We had the profilers looking at this as well.

We had surveillance on him. We knew more about him than he knew about himself. And that’s not arrogant saying that because we had been watching him so closely. So what we did was I don’t go into too much detail on this we sat him down, and one of the agents, Dave Falkner, literally walked him through his entire life from his birth to the moment that he called into the Soviet Embassy in January of 1980. And then Dave played Dave and Butch. But Dudley Hodgen’s name. He goes by Butch. They played an audio tape for him. And Butch later told me, he said he had a cup of coffee in his hand and the coffee was spilling all over his hand because he was shaking so badly. After they played the tape and his voice is on the tape after they ended the tape, he said, no, you may think that’s me, but that’s not me. Butch said he said you know, I did two tours in Vietnam and I said, My hearing is not very good at all. He said, but that sure sounds like you.

And they were off to the races. They were off to the races. And so we interviewed him that afternoon, and it was a beautiful afternoon in Annapolis at the time. So we interviewed him that afternoon and he gave us we had to make the elements of the espionage statute. And basically, it’s pretty straightforward. National defense information. Got to be national defense information voluntarily given to a foreign power. Oh, gosh, it’s been a while now. A foreign power or agent of a foreign power, I think those are the elements. Maybe one more forgive me, I just don’t remember. It’s been a while, but we got about three of them. And the fact that he was fully aware that it was espionage in other words in other words, he had to have guilty knowledge that he did it. If you do it by accident or something, that’s not espionage. He has to voluntarily give it that word. The voluntariness issue. And what happened was our game plan was to let him go because we didn’t want to spook him. And we got three, and we were high five. And then a series of issues occurred and we had to call him back that night.

So he came back that night and he was interviewed again, and that’s what he said. Butch said to him, looked at him, he said, no, you knew this was classified, didn’t you, Ron? And Ron lowered and said he said, yeah, I know it was classified. And you knew that you were giving them classified information, and it was voluntary, didn’t you? And he said yes, I did. Bingo, we got them. There you go. He said the whole thing right there. So we arrested him right on the spot, and in fact, he just died. I don’t know if you read that about two weeks ago. Yeah, he did his full 30 years in prison, which is life in prison, but it was quite a case. It was really a seminal case and became a wonderful case study done in Quantico for counterintelligence agents, and I’m very proud of it. I’m very proud of all the men and women, and it wasn’t just men. All the men and women that worked on that case were just people you want to be around all the time, so to speak.

Justin Black, Spycraft 101

Yeah, I mean, justifiably so that sounds like a pretty amazing investigation there, and a successful closure, because 30 years in prison for espionage I’m not an expert on sentencing guidelines or anything like that, but it seems like a lot of times people do not get super long sentences in the US. For espionage, so that seems pretty significant to me that you were able to get 30 years for him, right?

Ray Batvinis

Lipka got 18 years. I think Michael Walker, John Walker’s son, got 25 years, but he was released after 18 for good behavior, so some of them get far less. We did the Dolce case of an average improving ground. Dolce got ten years. A lot goes into it. People just don’t completely grasp what goes into the mix. Yeah, some of them don’t get the full time. Hanssen will never get out. For example, he’s got life without parole. Same thing with Rick Ames. No, they’re not going anywhere.

Justin Black, Spycraft 101

Right? Absolutely. Yeah, you’re definitely right about that. Well, that’s fascinating stuff. It sounds like quite an investigation, and I did have an episode a while back, and we talked about a guy on that one named Gennady Vasilinko, and from what I understand, he was handling Pelton for at least a period of his espionage career. Do you know much about Vasilinko yourself?

Ray Batvinis

You’re really taxing me here, my friend.

Justin Black, Spycraft 101

Sorry about that.

Ray Batvinis

That’s okay. There was very there was very little, very virtually none of the handling of him was in the United States. The way they handled him the way they handled him was they sent him to Vienna, okay? He would sit down it was very complex. He would sit down and answer questions. They took him, I think, to the Soviet embassy in Vienna, and he was there that he because he no longer had access to documents. Okay, so normally there’s a dead drop or filled with documents. He had no access to documents. He had already burned his bridges and left NSA. So what they had to do was sit down there, sitting and interrogate him for long periods of time to get what was in his head, what he remembered. And they could only do that in a location that was comfortable for them. They would never do it in the United States, never, because this is too hostile for them at the time, but they could do it in Vienna because they felt comfortable operating in Vienna. And what they did was and I’m not an expert on this, but what they did was they had a case officer like Vasilinko, and they would have a specialist from their version of NSA come in with questions and Pelton, I think, if I remember correctly, said he never saw that person.

Ray Batvinis

He was always behind a wall or in another room. But Vasilinko would ask the questions and he would describe the answers and write the answers down for hours and hours and hours about what he knew about NSA and Soviet and NSA successes and lack thereof are going after going against soviet ciphers and super encipherments.

Justin Black, Spycraft 101

Wow. You said I’m really taxing you, but you certainly recalled a lot of that out of the decades.

Ray Batvinis

Yeah, well, it’s a case you don’t forget, and when you wrote your notes, I use the best my memory, if I could remember what was going on. That’s what it was all about.

Justin Black, Spycraft 101

Sure. The reason I brought up Vasilinko was that I did an episode about him, and I haven’t spoken to him myself. I spoke to an author who wrote about him, but Vasilinko, he ended up getting arrested and spending some time in prison in Russia. And then he was freed and brought back here to the US. In 2010 as part of that prisoner exchange through Vienna, as a matter of fact. And hopefully he is somewhere in northern Virginia just living his life at this point. And that’s really, really interesting to me that, you know, this major case with a serious American traitor and the Russian who is handling him ends up being one of the pawns in the game between the two countries, and we take him back. So he’s living free and clear somewhere in northern Virginia right now, I believe.

Ray Batvinis

Yeah. It’s interesting, isn’t it? Yeah, that works out. Yes.

Justin Black, Spycraft 101