The Strange Wartime Odyssey of Louis C. Beck

By RAYMOND J. BATVINIS, Published in the World War II Quarterly, 2008

Like many a steamy summer evening in New York City, 11 July 1940 was no different when the SS Manhattan, like dozens of times before, gently slipped its lines, slid unnoticed into New York harbor, passed quietly through the Narrows into the Lower Bay near Sandy Hook, and slowly steamed out into the Atlantic.

An old United States Lines workhorse, the massive ship was outward bound on a twenty-five-hundred-mile voyage to Lisbon.

Its third roundtrip voyage to the Portuguese capital in as many months; the mission always the same – to take on the ever-growing numbers of anxious Americans, stranded in Europe by Adolf Hitler’s stunning invasion of France, and return them to the safety of American shores.

On its two previous trips, the ship had sailed empty from New York and filled to the brim with passengers on its return leg.

With travel to Europe essentially at a standstill, the ship’s east bound voyage took on an eerie ghostlike quality; a huge lumbering passenger vessel with empty staterooms, vast dining areas with no guests, silent decks absent of any walkers taking in the sea air, no chatter, and service personnel with no responsibilities or duties, idling away their time until they reached Portugal.

This trip to Europe, however, was different. Sailing from New York on the virtually empty ship were five strangers traveling together, all young men in their thirties, all well groomed, well dressed, well educated, well mannered, polite, friendly in a cautious way, and all under the strictest orders to speak with no one aboard the ship.

These five passengers were FBI special agents whose lives, during the eight weeks since German forces smashed into France, had changed in ways they could never have imagined.

The five special agents had been assigned to FBI field offices around the country conducting routine investigations, when suddenly and inexplicably they received instructions to immediately report to FBI Headquarters in Washington, D.C.

There they were met by Edward Tamm, FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover’s head of investigation, who ordered them to wrap up their affairs and prepare to leave immediately for Europe.

Their job: serve as diplomatic couriers for the Department carrying pouches containing all manner of sensitive documents between European capitals now caught up in war.

How long would they be gone; that was a question none of them dared ask.1

Their mission was prompted by two recent crises spawned by a combination of espionage and a serious breach of security in the U.S. government’s world-wide communications network.

Tyler Kent Case/Henry Antheil Case

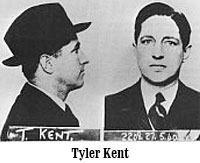

It began ten days after the surprise German attack on Holland and Belgium when Tyler Gatewood Kent, a young American code clerk working in the U.S. embassy in London, was arrested by British authorities on espionage charges.

It began ten days after the surprise German attack on Holland and Belgium when Tyler Gatewood Kent, a young American code clerk working in the U.S. embassy in London, was arrested by British authorities on espionage charges.

Assigned to London since September 1939, after five years as an embassy code clerk in Moscow, the twenty-nine-year-old American was charged with violating the British Official Secrets Act for stealing diplomatic cables from the embassy, and then passing them to the British Union of Fascists for transmission to Rome and Berlin.

News of Kent’s treachery staggered the State Department leadership.

Assistant Secretary of State Breckinridge Long, who was responsible for managing the State Department’s worldwide codes and communications systems, was dumbstruck.

Overwhelmed by a German army now slicing through Western Europe and the critical need for secure communications more essential than ever before, he now faced his most dreaded fear – America’s most sensitive diplomatic codes were completely compromised.

Referring to Kent’s arrest, Long confided to his personal diary that his act of espionage “may mean that our communications system is no longer secret.”2

Still staggering from Kent’s treachery, the State Department received the knock-out hit with the report of the sudden death, in June of 1940, of Henry Antheil, a U.S. Navy enlisted man assigned to the American legation in Helsinki, Finland.

Before his transfer in September 1939, he too had worked for five years with Kent at the American Embassy in Moscow.

He died when the Estonian airliner that he was traveling on was shot down over the Baltic Sea by Soviet fighters.

At the time of his death, he was a cryptologic courier who maintained diplomatic communications machines and supplied new codes and ciphers for American embassies throughout Central Europe and the Soviet Union.3

Henry Antheil was born into a German Lutheran immigrant family in Trenton, New Jersey in 1912.

His older brother, George Antheil, was a noted musical composer, then living in Hollywood, California, who had studied piano under Constantin von Sternberg and Ernest Block in Paris in the 1920s.

George had ushered in something of a revolution in musical composition with his use of varied and unusual sounds, producing, at the age of twenty-four, the Ballet Mécanique, his best known composition.4

In Paris, George married Boski Markus, a Hungarian Jewess, who he met while traveling through Austria.

Theirs was a world of the Left Bank; avant-garde artists of all varieties and genres; including internationally known writers like Gertrude Stein, James Joyce, Ernest Hemingway; painters Pablo Picasso and Salvadore Dali; as well as musical legend Igor Stravinsky; and Ezra Pound, the philosopher.

A decade later, he and Boski moved to Hollywood where he launched a musical career composing more than 300 works in all major genres including symphonies, chamber works, operas, and film music for such movies as The Pride and the Passion and The Young Don’t Cry.

He also authored articles, books, and an autobiography, Bad Boy of Music.5

Following Henry’s death, Arthur Schoenfeld, the U.S. Minister to Finland, ordered his secretary, Robert McClintock, to gather up Antheil’s personal belongings for shipment to his family.

What began as a routine inventory on 20 June 1940, quickly became a forensic investigation. Found among Henry’s clothing were two cards with the “neatly typed code room vault combination lying on a shelf of his wardrobe.”

What began as a routine inventory on 20 June 1940, quickly became a forensic investigation. Found among Henry’s clothing were two cards with the “neatly typed code room vault combination lying on a shelf of his wardrobe.”

A more careful examination of his closet revealed “a dozen large manila envelopes containing [Antheil’s] private files.”

Most were innocuous, but one folder caught McClintock’s entire attention; it contained evidence of deliberate tampering, alteration, falsification, and suppression of coded telegrams, confidential messages, penciled drafts of telegrams attached to the coded version; confidential communications decoded by Antheil – never delivered to the ambassador; and telegrams prepared by the ambassador, rewritten and encoded by Antheil and then transmitted by him over the ambassador’s signature.

McClintock next discovered a never-reported letter addressed to Antheil dated 30 November 1938 from someone identifying himself as Alexander Ivanovich Fomin; a military officer in the Soviet Army.

Fomin wanted to “propose my services to you [Antheil]” by providing “information of a military nature, which I hope are new and very important to you.”

The documents pointed to one conclusion – Antheil’s desire for a transfer out of Moscow, which forced his alteration of telegrams in a desperate attempt to emphasize his ordeal.

He complained of ill health; the need for a better diet and a fresh environment where he could “enjoy normal living conditions.”

In another coded message, he posed as a physician claiming that his patient’s physical condition was so “poor” that he needed an assignment where he could get “wholesome food.”6

For years, Antheil had appealed for a reassignment out of Moscow, but for years the State Department, which was facing Draconian budgets and shortages of trained personnel, simply ignored his pleas.

McClintock’s growing supply of evidence suggested that while assigned to Helsinki, he again panicked when he learned of a possible transfer to Stockholm.

Reverting to his old habits, Antheil once again falsified telegrams from the ambassador to Washington, describing himself in one message as essential for the effective functioning of the legation as he is “one of the Department’s three most highly experienced code men.”

In another he audaciously lied about an influenza outbreak; a serious situation which made his services “urgently needed” in Helsinki.

Before McClintock had even finished his inventory, he was forced to concede to his superiors in Washington that the “dangerous disregard which this supposedly experienced and expert code clerk showed for the first principle of preserving the secrecy of codes” placed State Department communications at great risk.7

McClintock’s initial findings were only the prelude for more horrific discoveries to come.

For mingled among the falsified telegrams and code room and vault door combinations were copies of correspondence between Henry and his brother in the United States.

A closer look at the letters revealed that Henry had been secretly supplying George with information about the events unfolding in Europe, which he gleaned from State Department cables; information that George then used for a book that he published in 1940 entitled The Shape of the War to Come.8

Both brothers understood that caution was in delicate balance with a steady supply of valuable secrets.

George urged Henry to be “patient” with him [George] as he was not “accustomed to using codes, secret inks” while admitting that it took him “quite a little while to figure all of this out.”

In the end, however, he suggested the “more [information] you [Henry] send me the easier I shall write my book.”

Using a simple number transposition code system that they had concocted, Henry supplied answers to more than seventy highly detailed questions posed by George.

Among the intelligence gems that Henry disclosed were the possible dates for the German invasion of France; the statistical details of German oil reserves, German airplane production, submarines, “super tanks with which they intend to gradually mass a great offensive movement on the Maginot;” as well as German strategic intentions in the face of different scenarios suggested by George in his questions to Henry.9

Reeling from the Kent debacle and now the Antheil treachery, Long quickly recognized the common denominator in the bewildering tangle of reports that he was receiving from London and Helsinki.

Moscow was the key.

“The disturbing part” he recorded “is that this clerk from Helsinki and the one from London served together in Moscow. The one in London had a Russian woman he associated with and the one in Tallin [Antheil] seems to have had a Finnish lady friend. But we do not know that she was in Moscow. Both of them spoke Russian and both of them were indiscreet.”10

With Atlantic shipping in turmoil, and facing a worldwide communications compromise, Long was very short on options about a next move.

At the same time he could not escape the gnawing fear that other Americans were also involved.

Initial reports from London about the British investigation of Kent suggested that his co-worker, a code clerk recently reassigned to Madrid, may have conspired with him.

Long instinctively wanted to send a message to the American legation ordering an investigation of the man. Yet he feared that “the very man who was the subject of the telegram would decode the message;” even worse, he might use Antheil’s tactic of responding to Long’s message “without the knowledge of the Charge’ d’Affaires.”

Another concern was that long-standing State Department policy may have facilitated Antheil’s espionage.

For years, American diplomats serving abroad were permitted to send sealed personal letters and packages to the United States and other American posts through the diplomatic pouch without censorship.

Faced with these concerns, Long concluded that he had no choice but to take some corrective action.11

Investigating foreign espionage thousands of miles away from U.S. shores was only part of the State Department’s problems.

Diplomatic bags moving from one continent to another went by ship in the custody of the captain who turned them over to an American courier upon arrival at a European port.

When the war broke out, the U.S. had only five couriers based in Paris covering all of its embassies in Europe.

With Belgium, Holland, and much of France now under German occupation; armies still on the march, border checkpoints tightening daily; and the volume of diplomatic mail exploding, the base for courier operations was shifted to Geneva, Switzerland and the courier cadre was doubled with the assignment of the five strangers now sailing across the Atlantic. 1

Peter Hoehl, Horton Telford, William Doyle, Louis Beck, and Ray Leddy were now bound for Europe.

Hoehl spoke German, as did Telford and Beck. Doyle and Leddy spoke Spanish; all were Geneva bound – except for Beck.

By secret prearrangement before leaving the United States, he traveled on to Berlin where he conferred with State Department security officials; then on alone to the Soviet Union where he began service as an “Internal Messenger” at the American Embassy in Moscow in August 1940.

For the next fifteen months, he carried the diplomatic pouch, and quietly investigated Kent and Antheil’s activities during their Moscow assignment; all the while secretly reporting to Washington on embassy security conditions and the behavior of its personnel.13

For the next fifteen months, he carried the diplomatic pouch, and quietly investigated Kent and Antheil’s activities during their Moscow assignment; all the while secretly reporting to Washington on embassy security conditions and the behavior of its personnel.13

Beck’s new colleagues, from Ambassador Laurence Steinhardt to the lowliest clerk, had no idea of his FBI affiliation or Russian language fluency.

Born in Milwaukee, the slightly built, thirty-two-year-old special agent from a blue collar German household, grew up amidst the sights, sounds, and smells so common in any tough urban working class neighborhood.

As a child he absorbed, both at home and in the street, the language skills that would prove so useful in the years to come.

Later, the family moved to southern California where Louis received his higher education.

Described as a quiet and highly intelligent man, he received an undergraduate, graduate, and law degree from the University of Southern California during the early 1930s; followed by employment with the Bank of America in Pasadena, California before joining the FBI as an agent in February 1939.

After training school and a brief first office assignment, he was transferred to Detroit, where he was assigned at the time of his July 1940 orders to Washington.14

Crossing the Soviet border from Riga, Latvia must have been a shock to the young undercover agent.

Even in August, traveling by rickety train across the Russian countryside, the endless landscape of vast under-cultivated fields worked by drab Russian peasants made an indelible impression on him.

Writing fifteen months later he still vividly recalled the “brown, water soaked fields…broken only by a few dirt roads deep with mud…horse drawn carts” and the occasional village “composed of ancient, unpainted log houses decorated with ornate carvings.”15

Arrival in Moscow, the symbol of seventeen years of Stalinist rule, certainly offered no relief.

The Russian capital that welcomed him was a blend of gloomy factories surrounded by high barbed-wire walls, staffed by political prisoners, and topped by guard houses with armed soldiers.

It was a dreary, joyless place, displaying little life, with none of the simple amenities of a large European city – varieties of hotels, restaurants, nightclubs, clothiers, and stores that any traveler could expect.

Instead, he found only cheerless Russians with their heads down, eyes cast to the ground, trying simply to stay alive, and never acknowledging foreigners for fear of arrest.

Embassy life was just as disappointing. The relentless and unpredictable disruptions: heat in the winter time; gas for cooking; electricity to power refrigeration and lights; shortages of refrigerators, matched in equal parts with scarcities of fruits, vegetables, meats, and other basic life necessities, were a matter of routine that was simply taken for granted.

Worse still was the relentless sense of personal isolation and boredom brought on by chronic shortages of American newspapers and magazines, frequent postal delays, and a non-fraternization policy with a Russian population that was itself forbidden to speak to foreigners.

Contact with the outside world was just as demoralizing.

The primitive Russian telephone system required callers to go the central Moscow telephone station at all hours of the day and night where they would wait interminably to place and receive international calls.

So dismal were the living conditions that even Ambassador Steinhardt was forced to give voice to the realities of Moscow life.

“All in all,” Steinhardt complained to a friend “life here is no bed of roses – excepting the thorns.”

It was a thoroughly demoralizing environment which only eased the task of the ever-watchful and oppressive NKVD counterintelligence service.16

US Embassy Security Situation

One of Beck’s most important assignments was the assessment of embassy security, particularly the code room and its personnel. His duties offered him free day and night access to all offices, sections, and personnel.

With a mission to observe and report, he followed every feature of the embassy’s daily routine including the foibles and behavior of the staff: a task that quickly opened his eyes to the ease with which the local counterintelligence service could assess and recruit the American staff members for espionage.

Thirty-five American employees together with thirty-three additional Russian employees working as translators, librarians, typists, economic advisors, telephone operators, and messengers made up the full embassy complement.

The Americans, except for the ambassador and four clerks, lived in the embassy building composed of twenty-five apartments with “at least one Soviet servant for each.”

He found an atmosphere of general malaise and indifference among the American embassy staff resulting in a disregard for the most basic security procedures.

Flagrant security violations included fraternization, sexual relationships involving embassy officers and Soviet women; open homosexual relations among staff members, and with foreigners; as well as illegal money and gold transfers.17

Serious code room security deficiencies were also uncovered.

Code clerks behaved indifferently toward their duties with long absences from the code room; unattended confidential cables laid out in the open; and unauthorized persons chatting at length with the code clerks in the code room.

On his second night at the embassy, as Beck casually strolled through the open code room door, he found the safes unlocked and code books lying on a table together with cables waiting encoding and decoding.

As for the code clerk on duty, he evinced a “complete disinterest” in his work and went for a break leaving the Code Room under Beck’s “complete control.”18

Next to get his attention was the destruction of confidential material.

Original drafts of coded messages combined with the original handwritten or typed drafts of the message in coded form were combined for burning in the embassy furnace, a security failure that simplified NKVD efforts to decipher confidential embassy communications.

Confidential papers were burned with no security oversight to ensure complete destruction.

Even more worrisome was the habit of Russian staff members loitering unsupervised in the basement at day’s end, watching the fire.

Later, Beck discovered that the bundles of paper were only partially destroyed; after a few minutes many messages could be removed from the furnace and easily read.

To Beck’s dismay, only the Soviet employees knew if the bundles tossed into the fire were completely destroyed.

A cursory search of the remains uncovered a number of original messages that he removed “surreptitiously from the fire” that included confidential cables prepared by Ambassador Steinhardt concerning the Kent and Antheil cases.

So serious were his concerns that he soon took over the job of “personally” burning all confidential trash.19

After weeks of careful observation, he concluded that it was “practically impossible for a single man to live a normal life while attached to the American Embassy at Moscow.”

State Department policy, at the time, required the assignment of only unmarried men to Moscow.

They were quartered two to an apartment above the embassy offices; a condition that confined friendships only to the employees working in the embassy.

Russians fraternizing with foreigners “generally disappear[ed] and it is understood they are exiled to Siberia.”

An absence of conventional female companionship regularly forced these men to turn to a group of Russian prostitutes who concentrated “only” on embassy staff members.

Their knowledge of the goings on in Moscow diplomatic circles was “amazing;” when new American staff members arrived in Moscow they were soon receiving telephone calls from one of the girls.

So aggressive was the NKVD that they tried to assign a prostitute girlfriend for each embassy staff member interested in such pursuits.

To improve its chances, the local security service constantly watched the front of the embassy building.

When a girl from the “regular group” approached an American no effort was made to stop her; an unauthorized female in such company was always followed until they separated for the evening, after which she was taken into custody and questioned.20

One particular case involved Donald Nichols, an embassy vice-consul.

Following Tyler Kent’s reassignment to London, Nichols moved his former Russian girlfriend, Tatyana “Buba” Ilovaiskaya, in a dacha that Nichols rented for her in the suburbs of Moscow.

Ilovaiskaya, an embassy translator, lived a far different life than average Muscovites. Buba wore expensive clothes, had her own driver’s license, and traveled extensively throughout Europe; all distinctions “unusual among Soviet citizens.”

The country home, which she shared with Nichols, also served as a getaway where Russian women entertained embassy clerks. Beck later reported the common rumor that Buba was an NKVD “agent.”21

Prostitutes, who claimed no knowledge of the English language, had little difficulty extracting information from diplomats who neither understood nor spoke the Russian language.

Current news from the United States, so constricted for the Americans in Moscow, often forced conversation away from mundane topics such as sports, politics, or other non- sensitive issues to gossip about embassy matters.

Beck suspected that the women actually understood English and reported what they learned to their NKVD controllers.22

Revelations of “sexual perversion among staff members” also emerged. It was common knowledge, Beck discovered, that Robert Hall, a code clerk, was romantically involved with George Filton, the ambassador’s secretary; often meeting secretly in the embassy’s code room.

Hall became so distraught over his situation that he eventually resigned from the State Department and returned to the U.S. on his own.

Filton, who had been active in Moscow’s underground gay community for a number of years, had contemplated suicide because his desperate transfer requests were repeatedly rejected by Washington.

Beck warned that the NKVD was fully aware of these problems and routinely used these human vulnerabilities for blackmail purposes.

Such unchecked behavior, in his view, in the Moscow environment served “as a lever [for the NKVD] to pry confidential information from them, this observation being particularly pertinent to the ambassador’s secretary.”23

Within weeks of his arrival, Beck began taking corrective action.

With couriers so scarce on the European continent, the ambassador had assigned Sylvester Buntowsky, a navy yeoman, responsible for the maintenance of coding machines, and Nichols to carry diplomatic pouches between Berlin and Moscow.

Beck suspected both of illegal currency dealings with good reason.

During his three-year Moscow assignment, Buntowsky had considerably enriched himself; wealth that included large unexplained sums of dollars and rubles, “a new Ford car,” expensive clothes, a “luxurious apartment formerly the property of a Swedish nobleman,” and a country home in the suburbs where he lived with his Russian girlfriend.24

Without tipping his hand, Beck devised a scheme to keep both men in Moscow and away from the diplomatic pouch.

During a trip to Stockholm in September 1940, Beck secretly met with Diplomatic Security Officers Lawrence Frank and Avery Warren in their room in Stockholm’s Grand Hotel to discuss his findings in detail.

They agreed to investigate conditions further upon their arrival in Moscow without identifying Beck as their source.

They also concocted a plan for placing courier duties exclusively in Beck’s hands and insisted on briefing Ambassador Steinhardt about Beck and their course of action.

Beck objected for good reasons; the ambassador was already wrestling with the fallout of two American spies who had served in his embassy, one now dead and one facing prosecution in London.

Beck now feared for the security of assignment, not to mention the ambassador’s dyspeptic reaction upon learning that J. Edgar Hoover now had a spy working in his embassy.

Frank and Avery, nevertheless, were adamant. Steinhardt had to be informed; his authorization for Beck’s service as a diplomatic courier as well as any new corrective security actions would be required.25

Over the next twelve months, Beck’s identity was safeguarded by the ambassador and courier duties were handled exclusively by him.

Security procedures, including restrictions on code room access and discussions of coded messages, were significantly strengthened.

Custody of coded messages was restricted to authorized officials who could only read them in the code room and in the presence of the code clerk.

The senior code clerk was made personally responsible for burning all coded messages and drafts of coded telegrams in the code room.

Embassy clerks could no longer accompany the diplomatic courier to other countries and, in a radical departure from previous State Department policy, all personal mail and packages sent through the diplomatic pouch would undergo rigid censorship.26

By July 1941, with his Moscow assignment at an end, Beck felt confident that corrective changes were in place and the situation had significantly stabilized.

The ambassador, oblivious for so long of his staff’s “carelessness and laxness,” now routinely stayed abreast of all embassy security matters.

Code room and file room procedures, so porous for so long, were significantly strengthened so that information “cannot leak out of them.”

Finally, certain embassy employees were “recommended for transfer,” closer controls were imposed on courier services and censorship of personal mail became a common practice.27

The Faymonville Crisis

During the summer of 1942, another crisis at the American embassy in Moscow once again altered Beck’s life.

This problem had its roots in the fall of 1941, when a joint U.S. and British delegation led by the American Averill Harriman and Britain’s Lord Beaverbrook journeyed to Moscow to discuss the extension of Lend-Lease aid to the Soviet Union in the wake of the surprise German invasion in June 1941.

Massive infusions of U.S. war materiel were deemed vital for keeping the Red Army fighting in the field and staving off a Russian defeat.

Protocols were quickly signed for the shipment of the necessary supplies to Russia together with arrangements for the permanent assignment of a small U.S. military mission, which would remain in Moscow to coordinate the needs and requirements with the Russian authorities.

This expedient was characterized by confused lines of authority that cut across traditional jurisdictional boundaries of a number of U.S. government departments, including the Department of State.

In this case, the new head of the U.S. Moscow military mission answered only to Harry Hopkins, the chief of the Munitions Assignment Board, who lived in the White House and answered only to President Roosevelt, and Major General James Burns, Hopkins’ Executive Secretary.28

Colonel Philip Ries Faymonville, a member of the Harriman-Beaverbrook delegation, remained in Moscow as head of the mission.

A 1912 graduate of West Point with thirty-four years of army service, Colonel Faymonville appeared, on the surface, as the ideal choice for this assignment.

While serving as President Roosevelt’s White House aide de campe he had developed close ties with both Mrs. Roosevelt and Hopkins.

A graduate of the Industrial and War Colleges, he had served as an ordnance officer during a World War I expedition to Russia, was fluent in the Russian language, and served for five years in the 1930s as the U.S. military attaché in Moscow.

A bachelor and a solitary man, Faymonville was generally viewed as an intellectual who loved opera and the ballet and was considered by many in and out of the American government as the best informed U.S. official on Russian matters.

William Bullitt, the U.S. ambassador to Russia in 1934, was initially impressed with how “conscientiously he prepared himself as an authority on Soviet Russia.”

He was a man with strong and unconventional views who was not afraid to voice them.

When leading War Department experts gloomily predicted the imminent defeat of the Red Army during the summer and fall of 1941, Faymonville, a lone dissenter, correctly predicted that the Russians would eventually stop the Nazis in their tracks.29

Faymonville also had critics who questioned his objectivity and many incautious remarks regarding all matters Russian.

Charles Bohlen, a State Department Soviet expert who had served with Faymonville in Moscow, considered him “a weak link on the staff” because of his bias and impaired judgment regarding the Russians.

Loy Henderson, another senior State Department European specialist, who observed Faymonville’s behavior first-hand in Moscow during the summer and fall of 1942, developed serious doubts about his solicitous attitude toward Russian interests.

Doubts about his judgment soon gave way to questions about his loyalty; suspicions which led his detractors to refer to him as America’s “Red General.”30

Six months after the colonel’s posting to Moscow, President Roosevelt appointed William Harrison Standley to fill the vacant post of ambassador to the Soviet Union in February 1942.

A naval academy graduate with forty-two years of naval service, Standley had retired in 1937 following four years as Chief of Naval Operations.

Deeply suspicious of Stalin and his henchmen, who only eight months earlier had been Germany’s ally, the new ambassador, no novice to diplomacy, anticipated a Moscow assignment that would demand regular access to the Soviet leadership.

Instead, to his surprise, the German army’s race toward Moscow had forced the evacuation of foreign diplomats to the city of Kuibyshev – six hundred miles east of the capital.31

While Standley was isolated in this Ural Mountain city, Colonel Joseph Michela, his military attaché, and Captain William Duncan, the naval attaché, remained in the Russian capital.

With Stalin and his government still functioning in Moscow, an increasingly frustrated Standley soon found that he had no access to Soviet officials and little to occupy his time.

Soviet liaison officials routinely rejected the ambassador’s requests for meetings and updates on political and military matters, while requests from Michela and Duncan to observe the Red Army in battle were similarly denied.

The explanation was always the same – a dangerous battlefield environment and the fluidity of the shifting front.

American embassy requests for military intelligence concerning such matters as German equipment, strategy, tactics, personnel, or anything else that would aid an understanding of the German fighting capabilities were also routinely delayed and denied.32

Faymonville, by contrast, was generally free to move about as he pleased with only a few restrictions, meeting regularly with Soviet military officials and sharing data with them.

Russian military officials rarely refused his requests to observe the fighting front.

Originally, he too had been moved east, but by early 1942 the Soviet government authorized his relocation back to Moscow.

His return to the capital accelerated the reports of his many conversations, discussions, and observations together with Soviet equipment demands; all of which he cabled directly to Burns and Hopkins in Washington, and without oversight by ambassador Standley or review by Michela for information of intelligence value.33

Tensions quickly rose, with Standley, Michela, and Duncan on one side, and Faymonville on the other.

With nowhere else to turn, a frustrated Michela, who was routinely cold-shouldered by Russian military officials, gradually began exerting pressure on Faymonville to supply him with the intelligence from his Russian contacts.

He flatly refused the request, telling the furious Michela that he did not answer to him or the ambassador. As the Lend-Lease representative in Moscow he worked for Hopkins and Burns in Washington.

His job was to get supplies to the Russians and ensuring the trust of the always-suspicious Soviets was an essential part of his mission: one that he feared would seriously compromise his effectiveness if the Russians learned about a confidential intelligence exchange with Michela.34

Over the next six months, the strain between the embassy and the military mission grew into outright hostility.

Standley appealed, without success, for Faymonville’s cooperation in the belief that the Lend-Lease military supply program involved delicate political questions falling under the admiral’s jurisdiction.

When demands for clarification of the situation from Washington failed to produce results, Standley, together with Michela and Duncan, returned to Washington to discuss the problem.35

During the summer of 1942, General George C. Marshall started receiving a steady stream of reports from Moscow concerning Faymonville’s attitude and his unquestioning endorsement for all Soviet demands for U.S. military equipment.

Promoted to Army Chief of Staff in September 1939 with a mission to rebuild the undersized American military, Marshall believed that army needs were just as important as keeping Russia in the war; particularly now as he prepared a U.S. force that would hit the North African beaches in the Fall of 1942.

Memories of those wartime Lend-Lease White House battles remained vivid more than a decade later when Marshall reminisced for his official biographer.

“Hopkins’ job with the President was to represent the Russian interests. My job was to represent the American interests and I was opposed to any, what I call, undue generosity which might endanger our security.”

Beck Returns to Moscow

Lou Beck’s career once again took a dramatic shift when Marshall ordered General George V. Strong, the G2 head, to secretly investigate the allegations against Faymonville.

Following his return from his first Moscow mission in the summer of 1941, Beck was assigned to the FBI’s Special Intelligence Service (SIS) in a new undercover role as a diplomatic courier.

Set up on 2 July 1940, as Beck was leaving for Europe, the SIS was America’s first top-secret foreign intelligence service.

With the nation embroiled in the Neutrality debate, President Roosevelt ordered Hoover to send undercover (UC) agents to Central and South American countries, where they posed as American businessmen in order to steal the economic, political, industrial, and military secrets of those governments.

By late 1941, this original UC group was augmented by FBI special agents posing as diplomats in U.S. embassies. Their role was to assist the UC businessmen in the speedy shipment of their intelligence reports to Washington.

These new “Legal Attaches,” as they were called, obtained confidential post office boxes in false names where they could secretly retrieve intelligence reports from the UC businessmen and then quickly send them by diplomatic pouch to Washington.

To this business and diplomatic UC cadre was added a new component; FBI agents posing as couriers who carried the diplomatic mail, while secretly acting as SIS “trouble shooters” and delivering the necessary cipher pads for the UC’s confidential communications.

Beck was serving as a courier when Hoover ordered him back to Washington a second time for a new Moscow assignment.37

After studying the background of the problem through a review of State and War Department cables and reports and acquainting himself with the personalities, Beck now had to create a cover position that would once again offer the flexibility to freely observe and confidentially report his findings.

His first order of business was a phony resignation from the Department of State.

In 1940, he was a State Department Internal Messenger in the embassy; this time the War Department made him a U.S. Army officer – a captain in the infantry. Captain Beck would serve as an assistant military attaché on the staff of Colonel Joseph Michela.

With no military training or experience of any kind, “Captain” Beck donned his new army uniform and departed for Moscow in September 1942.38

Little is actually known about his first five months at the embassy in Moscow. He clearly had a first-hand view of the chaos that was occurring around him.

The Faymonville, Standley, Michela, Duncan war was an open secret in Moscow’s diplomatic community.

On top of that, within days of Beck’s arrival, Loy Henderson, who was in Moscow conducting a security review of the embassy, handed Standley a “voluminous” copy of his findings, which years later the ambassador described as “complete and damning, citing many omissions and failures.”

With Henderson serving as acting charge d’affaires during Standley’s temporary return to Washington during the fall of 1942, Beck, most likely, spent his time as he did on his previous Russian assignment; asking questions, watching, observing, quietly examining files, and making discreet inquiries – all in an effort to develop his own sense of the problem.39

In Washington, Standley pled his case against Faymonville and the structure of the Russian Lend-Lease program with the Administration, the War Department, and anyone else who would listen to him.

During an Oval Office lunch with Roosevelt and Hopkins, he described the dysfunctional set-up and the difficulties that he was experiencing with it.

Roosevelt was startled to learn of Faymonville’s inability to resist “the demands of the Russians,” his refusal to cooperate with the ambassador, and the corrosive affect that it had on the ambassador’s role as the president’s personal representative in the Soviet Union.

During a War Department meeting, Marshall became “so exercised” over the ambassador’s briefing that he insisted the matter be taken up with the Russian Foreign Ministry at the earliest possible moment.

By the date of his return to Moscow in mid-December 1942, Roosevelt and Hopkins had accorded certain concessions to Standley that only temporarily satisfied the problem.

Many months earlier, Marshall, at Hopkin’s insistence, had promoted Faymonville to the rank of Brigadier General in order to enhance his status with the Russians.

Marshall, in a highly unusual move designed to equalize ranks, now promoted Michela to Brigadier General, while Admiral Ernest King, the Chief of Naval Operations, made Captain Duncan a Rear Admiral.

Finally, after considerable foot-dragging, Hopkins ordered Faymonville to submit to Standley’s “overall coordination and supervision” with additional instructions to keep him fully informed, consult with him, and follow Standley’s guidance “on questions political in character” and of “sufficient importance to justify his participation.”40

With reports continuing to flow into Marshall’s office from Moscow over the following months describing Faymonville’s continuing insubordination, an overburdened and now obviously exasperated Chief of Staff finally reached the breaking point.

The question in Marshall’s mind was why Faymonville, a West Pointer, a senior officer, with more than three decades of military experience “refused to cooperate with other U.S. missions in Russia.”

But behind his order lay a deeper fear, one that went beyond ego and petty bureaucratic rivalries: a grave concern that Faymonville’s “personal and official conduct was so pro-Soviet as to raise the question in some persons’ minds as to whether he was being blackmailed by the Soviet Government.”

Through General Strong, the order to produce a secret report for the Chief of Staff and the White House was communicated to Beck.41

By the time Beck returned to the United States in June 1943, he had produced a thirty-six-page study which one senior officer, familiar with the problem, later described as “shocking.”

Beck, ostensibly working for Michela and probably receiving inside information from him, nevertheless took no sides in the matter and produced a balanced study which spread responsibility around evenly among the cast of characters in Moscow and Kuibyshev.

He described Faymonville’s uncooperative and insolent attitude toward the ambassador, their shouting matches, and the ambassador’s public accusations regarding the general’s personal deportment, which led to a complete breakdown in their relationship.

Faymonville’s embrace of his unique access to the Russians, which he used to curry favor with visiting politicians and military officers from Washington, was also described as well as his negotiation of political agreements with the Soviet government without informing or consulting Standley.

Faymonville’s frequent demeaning of the ambassador behind his back, his references to him as a “dottering old fool,” his keen interest in replacing him as ambassador, as well as his stubborn refusal to cooperate with the military attachés also found their way into Captain Beck’s report.42

Criticism was also leveled at Duncan and the very unpopular Michela as well.

Described as strongly anti-Soviet, both officers accused Faymonville of openly saying that the “Soviets are the greatest warriors the world has ever seen.”

A view contrary to their belief that the U.S. was “being sold down the river” by the Lend-Lease program and “that we are ‘just suckers.'”

Another officer on General Michela’s staff, described as the “most anti-Soviet person in Moscow,” told Beck that he “does not hesitate to publicly state his contempt for almost everything Soviet.”

Then to his utter amazement, Captain Beck learned that “to the girls who visit [the officer’s apartment] he freely expresses his views, knowing that, and in the hopes that, these views will get back to Soviet officials.”43

What was reported next must have truly rattled Marshall.

In an unconscionable breach of Beck’s own security, Michela, fully aware that Beck had no military training or experience, used him as his “unofficial aide” so that the undercover agent could witness first-hand and “report to Washington” the treatment Michela received from the Soviets.

From February 1943 until his Moscow duties ended, “Captain Beck” directly participated in a series of regularly-scheduled meetings with all levels of Soviet military officials; an experience which reaffirmed his conclusion about the Russian disdain for Michela and their consequent refusal to cooperate with him and his staff.44

When one considers the unimaginable pressure on General Marshall as he struggled with the hourly management of millions of men at war throughout the world, one can only speculate on his reaction to the section of Beck’s report entitled “Dissatisfaction Due to Differences in Compensation & Inequality of Rank.”

Pulling no punches, the report described two points of “constant discontent”: the differences in compensation received by Michela and Faymonville and, second, Faymonville’s policy of “rapidly advancing those officers who are loyal to him.”

Faced with the monumental problems of supply, strategy planning, British military coordination, and the steady reports of mounting battle casualties, the normally composed Marshall must have shuddered with rage when he read Beck’s description of senior American military officers, in the midst of a world at war, publicly bickering over salaries and per diem allowances.45

Marshall received Beck’s report on 26 July 1943. The accompanying memorandum warned him that the Moscow situation, which was already known to the American press, “cannot fail to bring discredit upon the United States.”

It urged him to “immediately” relieve General Michela and recommend that Hopkins do the same with Faymonville.

Wasting no time, Marshall sent Beck’s “secret” report to Hopkins with a request that he return it to General Strong “as soon as it has served your purpose.”46

Hopkins returned the report to Strong on 12 August 1943: but not before sharing its contents with General Burns, his deputy Lend-Lease coordinator.

A furious Burns denounced the report four days later in a handwritten rebuttal to Hopkins.

Defending Faymonville from an investigation done “apparently without his knowledge and ability to defend himself,” Burns emphasized for his boss that no evidence of any blackmail of Faymonville was uncovered.

While attributing much of the “gossip and hearsay evidence” to Michela, Burns was forced to concede that Beck’s findings contained “much worthwhile information and analysis with reference to Faymonville.”

Then, in a blinding display of political obtuseness, Burns urged Hopkins to remedy the situation with immediate and decisive changes; first, “clear house” of all who are not loyally carrying out the President’s policies and, second, appoint a more compliant ambassador.

Lastly, Burns suggested that Faymonville remain at his post in Moscow with a new vote of confidence in the form of a promotion in rank – this time to major general.47

Marshall agreed with Burns about moving swiftly to clear house and correct what the Chief of Staff called the “mess” in Moscow.

Coordinating closely with Averill Harriman, the recently-chosen replacement for the retiring Standley, Marshall relieved Michela and ordered his return to the United States for reassignment.

His next step was the closing of the military and naval attaché offices, with Admiral Duncan reassigned to the staff of the new and reorganized Moscow military mission.

As for Faymonville, he remained in Moscow as a transitional figure until his replacement, Major General John Deane, a Marshall protégé, was comfortable in his new role.

At Marshall and Harriman’s insistence, Deane would manage the Lend-Lease program under the ambassador’s direct supervision – a decision that had a positive impact for the remainder of the war.

By the end of the year, Faymonville was back in the United States, reduced to his permanent rank of colonel and assigned to an ordnance position in Arkansas.48

With Colonel Faymonville off to his new state-side post, Captain Louis Beck quietly hung up his uniform and ended his strange fifteen- month military career.

Now free for other duties, Special Agent Beck was again back with the FBI’s SIS; only this time with new undercover duties at the American embassy in London.

Posing this time as an “Assistant Communications Officer,” Beck routinely traveled for the next year between Stockholm, London, Ireland, the Iberian Peninsula, and the U.S. secretly investigating the integrity of the State Department’s diplomatic courier process.49

After more than seven years of service, Beck resigned from the FBI in April 1946 and returned to California.

After a year of private law practice, he reentered government service joining the newly-formed Central Intelligence Agency.

He was initially assigned for a year to Athens, Greece and then moved on to Belgrade, Yugoslavia in 1948 where he reported on the emerging split between Stalin and Tito.

For the next two decades, he was an officer in the CIA’s Clandestine Service, serving in a number of foreign and domestic assignments.

Lou Beck retired from the CIA in the late 1960s and died quietly on 9 October 1995 in a Florida nursing home at the age of eighty-seven. He is buried in California.50

Notes

1. Horton Telford, interview by author, 11 September 1996, Rehoboth Beach, Delaware.

2. Raymond J. Batvinis, The Origins of FBI Counterintelligence (Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas, 2007), p. 175. For a summary of the Tyler Kent espionage case, see Batvinis, FBI Counterintelligence, Chapter 8. For the full story, see Ray Bearse and Anthony Read, Conspirator: The Untold Story of Tyler Kent (New York: Doubleday, 1991).

3. Batvinis, FBI Counterintelligence, p.171.

4. “George Antheil, Composer, Dead,” The New York Times, 13 February 1959, “He was an honorary member of the Paris police for his work in criminal typing.”

5. Batvinis, FBI Counterintelligence, p. 171; Loy Henderson letter to Alexander Kirk, 5 December 1936; Schoenfeld cables to Washington, 20 June 1940, 22 June 1940, 23 June 1940; Hull cable to Helsinki, 21 June 1940; McClintock cable to Hull, 27 June 1940; Fomin letter to Antheil, ?0 November 1938. The preceding citations (with the exception of Batvinis, FBI Counterintelligence) are from RG 59, Box 310, Folder titled “123 Antheil 56-133,” National Archives and Records Administration, College Park, Maryland (hereafter NARA); George Antheil, Bad Boy of Music (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, Doran, 1945).

6. McClintock cable to Hull, 27 June 1940, RG 59, Box 310, Folder titled “123 Antheil 56-133,” NARA.

7. Ibid.

8. Ibid.; George Antheil “Dear Hen” letter to Henry Antheil, 4 April 1940, RG 59, Box 310, Folder titled “123 Antheil 56-133,” NARA; Anonymous (George Antheil), The Shape of the War to Come (Self-Published, 1940).

9. McClintock cable to Hull, 27 June 1940, RG 59, Box 310, Folder titled “123 Antheil 56-133,” NARA.

10. Fred L. Israel, ed., The War Diary of Breckinridge Long: Selections from the Years 1939-1944 (Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 1966), p. 172.

11. Ibid., p. 176; N.P. Davis memorandum to Long, 3 June 1940, RG 59, Box 34, General Files of the Department of State (GRDOS), Central Decimal File (CDF) 1940-1944, Folder 151/1871/2, NARA.

12. Batvinis, FBI Counterintelligence, pp. 175-178.

13. Ibid.

14. Ibid.

15. “Memorandum Submitted by a Special Agent Who Recently Returned From A European Trip” (hereafter Memorandum Submitted by a Special Agent), 19 September 1941, OF10b, REPORT #921, Franklin D. Roosevelt Library (hereafter FDRL).

16. Steinhardt letter to Nathaniel Davis, 13 March 1940, RG 59, GRDOS, CDF 1940-1944, Box 17, Folder 051.61/74A, NARA.

17. Louis C. Beck Memorandum, 13 December 1940, OF10b, Box 22, FDRL.

18. Ibid.

19. Ibid.

20. Ibid.

21. Ibid.

22. Ibid.

23. Ibid.

24. Ibid.

25. Ibid.

26. Ibid.; Hull cable to all diplomatic missions, 9 August 1940, RG 59, CDF 1940-1944, Folder 051.01/583 and 051.01/551A, Box 34, NARA.

27. Memorandum Submitted by a Special Agent.

28. Rudy Abramson, Spanning the Century: The Life of W. Averell Harriman, 1891-1986 (New York: William Morrow, 1992), pp. 289-294.

29. Anthony Cave Brown and Charles B. MacDonald, On A Field of Red: The Communist International and the Coming of World War II (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1981), p. 336.

30. Ibid.

31. Ibid., p. 337; Admiral William Harrison Standley Alumni Folder, Chester Nimitz Library, United States Naval Academy, Annapolis, Maryland. Faymonville was a Major General and Michela was a Colonel.

32. William H. Standley and Arthur A. Ageton, Admiral Ambassador to Russia (Chicago: Henry Regnery Company, 1955), p. 239.

33. Ibid. Standley writes that Faymonville’s influence was so great that he was often referred to as the “General who called the turn.”

34. Ibid., p. 244.

35. Ibid., p. 245.

36. Larry I. Bland, ed., George C. Marshall Interviews and Reminiscences for Forrest C. Pogue, third edition (Lexington, VA: George C. Marshall Foundation, 1996).

37. See Batvinis, FBI Counterintelligence for details of the origins of the Special Intelligence Service; Special Intelligence Service Personnel List, author’s collection.

38. Oral History Interview of Major General Sydney Spalding, USA, Sydney Spalding Papers, United States Army Military History Institute (USAMHI), Carlisle Barracks, Pennsylvania. The oral history transcript contains a question asked of General Spalding regarding the author of the report. The interviewer asked Spalding if he was familiar with a “Captain Beck” who wrote the report and Spalding claimed that he did not know him; RG 59, GRDOS, CDF, Folder 121.5461/208, NARA.

39. Standley and Ageton, Admiral Ambassador, pp. 296-297.

40. Ibid., pp. 308-311, 314-315.

41. Memorandum prepared by Louis C. Beck titled “The Influence of Brigadier General Philip R. Faymonville on Soviet-American Relations” (hereafter Beck Memorandum), Sydney Spalding Papers, USAMHI.

42. Ibid.

43. Ibid.

44. Ibid.

45. Ibid.

46. General George V. Strong letter to Hopkins, 27 July 1943, Harry Hopkins Papers, Faymonville Folder, FDRL. J. Edgar Hoover was listed as a recipient of a copy of this letter, and the Beck Memorandum.

47. Burns memorandum to Hopkins titled “Secret Report on General Faymonville’s Personal and Official Conduct,” 16 August 1943, Hopkins Papers, Faymonville Folder, FDRL; Beck Memorandum. Burns must have been livid when he read, on the last page of the memorandum, a summary of his 4 June 1943 discussion with the person he knew only as “Captain Beck.” Burns told Beck that the United States is at fault for failing to send someone to Moscow who is trusted by the Russians. Beck reportedly asked Burns if the Russians’ failure to share information with the Americans concerning a common enemy “is not an unfriendly act.” Burns replied that the conflict in Moscow was due to “the military mind.”

48. Marshall cable to General Eisenhower, 22 September 1943, George C. Marshall Library, Lexington, Virginia; Abramson, Spanning the Century, pp. 350-351; Harriman memorandum to Marshall, 23 September 1943, Box 70, Folder titled “Harriman, W. Averell, 1942-1943,” George C. Marshall Library, Lexington, Virginia.

49. Serial #121.67/4153a, GRDOS, CDF, NARA.

50. The record of Beck’s resignation is contained in the author’s personal files; The author wishes to express his appreciation to Coleman Mehta for generously offering background information on Beck and for a copy of Coleman Armstrong Mehta, “‘A Rat Hole to be Watched’? CIA Analyses of the Tito-Stalin Split, 1948-1950,” North Carolina State University, Master of Arts Thesis, 2005; Copy of state of Florida “Certificate of Death” dated 18 October 1995; The author’s appreciation is also extended to former Special Agents of the FBI Henry Flynn, Larry Langberg, and Jack O’Flaherty for their investigative assistance in this project.

ORIGINAL DOCUMENTS (in .pdf):

- 20 June 1940: Telegram to Secretary of State concerning evidence about Henry Antheil’s activities

- 22 June 1940: Telegram on Antheil case

- 23 June 1940: Telegram on Antheil case; Translation of a Letter to Antheil from Alexander Ivanovich Fomin

- 19 August 1940: Use of Diplomatic Pouch (Department of State)

- 19 September 1941: Memorandum Submitted by a Special Agent Who Recently Returned from a European Trip (The Louis Beck Report)

- 16 August 1943: Secret Report on Gen. Faymonville’s Personal and Official Conduct

- 26 August 1943: Note on Antheil case

- 8 November 1943 and 1 November 1943: Memos for Harry Hopkins re BG Faymonville

- 20 June 1946: Recommendation for Distinguished Service Medal to Colonel Philip R. Faymonville, Ordnance Department

—————————–

RAYMOND J. BATVINIS is the author of The Origins of FBI Counterintelligence (Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas, 2007).

Dr. Batvinis, who served for twenty-five years as a Special Agent and Supervisory Special Agent of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), is the Executive Director of the J. Edgar Hoover Center for Law Enforcement and Adjunct Professor of Intelligence Studies at Mercyhurst College, Erie, Pennsylvania.

This article is Copyright © 2008 by World War II Quarterly. All international rights reserved.

WORLD WAR II QUARTERLY Volume 5 Number 2 2008

You must be logged in to post a comment.