Chapter One from “The Origins of FBI Counterintelligence” by Raymond J. Batvinis

Rumrich

He was a US Army deserter when he was arrested on February 14, 1938, and charged with spying for Germany. His name: Guenther Gustave Maria Rumrich.

He was a US Army deserter when he was arrested on February 14, 1938, and charged with spying for Germany. His name: Guenther Gustave Maria Rumrich.

Guenther was born in June 1911 in Chicago, Illinois, to Alfonso Rumrich, secretary to the imperial Austrian consulate general, and his wife, Jolan. Guenther was two years old when his father was transferred to Bremen, Germany; a year later, the family moved to Budapest, Hungary. He later lived with his parents and sister in Italy and Russia and was educated between 1919 and 1928 in Czechoslovakia and Germany.

Young Guenther elected to affirm his American citizenship in April 1929 when he applied for and received a U.S. passport at the U.S. consulate in Prague. He returned to the United States five months later and joined the army in January 1930, serving briefly in New York City at the general dispensary on Whitehall Street and the surgeon’s office on Governors Island.

Five months later he went absent without leave (AWOL) but surrendered to the military in August 1930. After serving six months in prison and forfeiting two-thirds of his salary, he was released and returned to duty, again assigned to Governors Island and the station hospital at Fort Hamilton, Brooklyn.

Thirty-three months after enlisting, he was promoted to the rank of sergeant and was discharged on April 27, 1933. Rumrich reenlisted the next day and spent the next two years assigned to the station hospital at Fort Clayton in the Panama Canal Zone, followed by a stint at Fort Missoula, Montana.

Rumrich went AWOL from Fort Missoula on January 2, 1936, and soon got lost among the throngs in New York City. Settling in Brooklyn, he began working at a string of low-level jobs, including restaurant dishwasher, language instructor at the Berlitz School of Languages, and technician with the Denver Chemical Manufacturing Company on Varick Street in Lower Manhattan. In April 1937, his wife, whom he had met in Montana, joined him, and they settled in an apartment in the Bronx.

At some point, Rumrich stumbled across a copy of Geheime Macht, the memoirs of Colonel Walter Nicolai, head of the German foreign military intelligence service during the First World War.

He was so impressed by the colonel’s exploits that Rumrich decided to offer his services to Germany and sent a letter to Nicolai through the German daily newspaper Voelkischer Beobachter.

Describing himself as a “high official in the United States Army” with access to important military information, Rumrich asked Nicolai to forward his offer to the “proper authorities.”

Taking a cue from Nicolai’s book, he suggested that the Germans contact him by inserting an advertisement in the New York Times public notices section addressed to “Theodore Koener—Letter received, please send reply and address to Sanders, Hamburg 1, Postbox 629, Germany.”

Over the next four months Rumrich waited patiently while his letter made its way to the Abwehr, the foreign intelligence service of the German military high command. The advertisement was eventually placed, and on May 3, 1936, Rumrich met a German agent in a New York City restaurant, where he was quickly assessed and signed up as an Abwehr agent.

Over the next twenty-one months, the success that had eluded Rumrich during his six years in the military was countered by the volumes of sensitive military data he stole and smuggled to Germany. When he finally sat down with the FBI and told his story, the U.S. government’s approach to countering espionage would change forever.

Rumrich’s value as a productive Abwehr agent grew steadily until his fortunes ended abruptly with his arrest in February 1938. Increasing carelessness and audacity doomed Rumrich’s brief career as a spy. At first, he would cautiously pick up information of value to the Abwehr using tactics that raised no suspicion and attracted no attention. Success and the financial rewards of espionage, however, led him to contrive high-risk ploys that would soon prove disastrous.

In late 1937 Rumrich received instructions to acquire information concerning venereal disease among U.S. military troops. A critical concern for any military commander is readiness for combat. General George Patton, commander of the Third Army, was in England in the spring of 1944, preparing for the invasion of Europe. He mused about the problem in his diary. “I can’t get anyone to realize,” he wrote, “that even without fighting, a unit is always about 8% below strength due to sickness etc., and that a unit 15% low in manpower is at least 30% low in efficiency.”

One way for a foreign intelligence service to assess foreign troop readiness in the 1930s was the acquisition of intelligence concerning the percentage of soldiers medically incapacitated by illness, injury, or disease. With the majority of the United States’ 138,000 military members serving overseas, facts and figures concerning venereal disease among American troops were critical for German military planning.

Venereal disease was such a serious problem in terms of lost duty time that in 1925 the surgeon general, writing in the War Department’s annual report, had described it as “the most important sanitary problem in the Army.” Only respiratory conditions caused more hospitalizations at the time.

U.S. military authorities began taking strong measures to control the problem. Intensive educational programs designed to warn soldiers about the dangers of venereal disease, as well as harsher measures such as loss of pay, reduction in rank, and even court-martial of infected soldiers, became standard military practice. Beginning in the mid-1920s, statistical data collected on the progress of venereal disease prevention efforts were turned into reports for War Department planning purposes. It was these reports that Rumrich was ordered to secure.

Rumrich had an advantage in his pursuit of army medical intelligence. Having served in a series of medical units in New York City, Panama, and Montana, he knew which information was valuable, where it was located, and how easily he could acquire it.

Assuming the role of a senior American military officer, Rumrich threw caution to the wind and simply telephoned the medical section at Fort Hamilton in Brooklyn. Identifying himself as a specialist with the U.S. Army Medical Corps, he told the duty officer that he had arrived in New York City for a conference on military readiness and discovered that he had left some important statistics on venereal disease at his office in Washington, D.C.

Aware of the lax security assigned to this type of information, he brazenly ordered the Fort Hamilton medical staff to deliver the data to him at the Manhattan hotel where he was staying. Without any verification of the caller’s identity; the sensitive documents were taken by a soldier to the Hotel Taft and handed over to Rumrich. Within days, this valuable information concerning the status of U.S. war-fighting capabilities and the readiness of American military units stationed throughout the world was on its way across the Atlantic into the waiting hands of German military authorities.

Rumrich’s brilliant intelligence coup only whetted the Abwehr’s appetite for more. His new mission—one that meant potentially greater rewards for Germany but that increased his risk of discovery—was to obtain blank U.S. passports. These were valuable commodities for both the Abwehr and the Soviet intelligence services, and acquiring them was a top priority for both. Using sophisticated technology available only in the most modern laboratories, blank passports could be forged so as to appear genuine even to experts examining them with the naked eye.

Because few Americans traveled abroad during the 1920s and 1930s, customs and immigration officials at border crossings were not adequately trained to spot forgeries, making passports valuable false identity documents for espionage agents across Europe and Asia. The U.S. Department of State’s Passport Office, keenly aware of the espionage value of passports, placed a high level of security on them, making theft almost impossible.

Rumrich’s previous gambit as a “senior American military official” had been so successful that he decided to try it again. Using a more audacious variation, he called the Passport Office in New York City from a telephone booth at Grand Central Station and identified himself to the incredulous clerk as Cordell Hull, the U.S. secretary of state. Using a hushed voice for dramatic effect, he explained that he was in New York City incognito and ordered the delivery of thirty-five blank passports to Mr. Edward Weston, supposedly an assistant secretary of state, staying at the McAlpin Hotel in Midtown Manhattan.

The dumbfounded clerk could not conceive of such a bizarre request. A quick check confirmed that Hull was in Washington, D.C., and the State Department had no assistant secretaries named Weston. A package containing blank passport applications, rather than the blank passports Rumrich had requested, was readied and sent on its way under the close observation of State Department investigators and the New York City Police Department. Rumrich was arrested by police officers on February 14, 1938, when he took possession of the package.

With Rumrich in custody, State Department officials immediately began questioning the lawfulness of the arrest. Although posing as a U.S. government official was illegal, ordering blank passport applications, even under these strange circumstances, was not.

Even more troublesome for the bureaucrats was the potential embarrassment to the State Department if Secretary of State Cordell Hull was subpoenaed to testify at a high-profile court proceeding in New York City against someone whose crime was questionable. Unaware that it had one of Germany’s most important spies sitting in jail, State Department officials saw only two options: turn Rumrich over to the military as a deserter, or release him.

Crown

In July 1937 British postal authorities received a report concerning the suspicious behavior of a woman living in Dundee, a sleepy little farming town in central Scotland. Daily shipments of mail and packages postmarked from countries in South America, Europe, and Asia were arriving at the obscure address, along with daily postings from the Dundee resident back to these and other foreign addresses.

People in Dundee regularly sent and received a steady and predictable stream of mail consisting of bills, family and business letters, packages, and so forth, but nothing reaching the magnitude of this person’s activities. The volume of mail soon caught the attention of the curious postman who handled the route.

On the surface, nothing illegal was happening, but given British anxiety over Adolf Hitler’s increasingly threatening behavior on the Continent, the postman passed his suspicions on to his superiors. The report was quickly forwarded through the British Postal Service, eventually making its way to London and the headquarters of the British Security Service, known as M15, which launched an inquiry.

Who was this anonymous person living quietly in Scotland? M15 quickly identified her as Mrs. Jessie Wallace Jordan, a hairdresser in her early fifties who worked in a local beauty shop. She lived in a tiny fiat on Kinlock Street in a working-class neighborhood, kept to herself, maintained a modest lifestyle on a meager income, and rarely traveled. With such blandly predictable behavior—except for her unusual mailing activities—and no friends or contacts that raised any security concerns, there was no reason for anyone to suspect that Mrs. Jordan was an espionage agent.

Surface impressions can be misleading, however, as British authorities soon discovered. A deeper probe by M15 officers over the next few months gradually uncovered a link between this obscure beautician and espionage.

Although she had been born in Scotland and was a British citizen, Jordan had been living in Dundee only since 1937, after residing in Germany for thirty years. Before the First World War she had met and married a German traveling through Scotland, moved with him to Germany, and acquired German citizenship. Her husband had served in the German army during the war, receiving wounds that later proved fatal. A second marriage in Germany had ended in divorce.

A closer look at her travel patterns only deepened MI5’s concerns. Jordan had told friends that she had broken all ties with Germany and that her only close relatives lived in Scotland; yet an investigation of her travel patterns uncovered a number of unexplained trips to Germany in 1937 that she had not mentioned to anyone.

MI5 veterans had long suspected the Germans and the Russians of conducting espionage in Great Britain, but in the nearly two decades since the end of the First World War, the understaffed and underfunded security service had unearthed little meaningful evidence.

In January 1938, however, MI5 arrested four spies involved in a Soviet ring that had been quietly stealing blueprints for naval weapons from the Woolwich Arsenal. Now, with the Dundee investigation, another act of espionage in the British Isles may have been uncovered, and like any sophisticated counterintelligence service, MI5 began thinking beyond Mrs. Jordan.

By secretly examining the contents of her mail and tracking her mailing patterns, MI5 hoped to find other spies operating in Great Britain, particularly moles burrowed deep within the British government and the military establishment. Even more significantly, the possibility loomed that Britain’s knowledge of German espionage could reach beyond its borders, offering the British a unique opportunity to identify, penetrate, and neutralize German and Russian intelligence operations throughout the world.

Surveillance of Jordan soon began producing encouraging results. Letters from the United States, France, Holland, and South America arrived with regularity. Her mailing habits, as one historian later described them, were equally prolific, “with bulging envelopes [sent] to all sorts of faraway places.”

Over time, a careful examination of her mail led investigators to conclude that the letters and packages were not intended for Mrs. Jordan; rather, they were destined for Germany and its intelligence establishment, as well as intelligence agents in other parts of the world.

Mrs. Jordan, as MI5 suspected, was a “mail drop,” or, in British counterintelligence terminology, a “live letter box.” She was a “cut-out”—an anonymous person living an obscure existence who received and forwarded mail without examining the contents, motivated by a sense of loyalty, financial compensation, or both. Regardless of her reasons, Jordan was clearly spying for the Germans, and the British began reaping valuable information about German agents and operating methods throughout the world.

MI5’s initial strategy called for discreet and indefinite surveillance of Jordan’s mail. Then, when it was satisfied that enough information had been acquired, it would develop a scheme to quietly intercede and gain control of the operation, without the knowledge of the Germans or the Russians.

On January 17, 1938, however, MI5 plans collapsed when Jordan received a letter postmarked from New York City. Calling himself “Crown,” the author began with a warning about local custom regarding forms of address. Expressing concern that “nothing arouses even the faintest sort of suspicion,” he informed his German bosses that the Scottish custom was to address a married woman using the first name of her husband, regardless of his presence in the house. Crown worried that although he might appear to be a “stickler,” “’Mrs. Jessie Jordan” was a trifle away from the usual designation.”

His next paragraph, however, stopped the British investigation in its tracks. There, Crown outlined his plan for the theft of “details regarding the coast defense operations and bases on the Atlantic coast.” These records, he explained, were kept in the office of a Colonel Eglin, the commander of Fort Totten in New York.

Crown proposed a scheme in which he would pose as the “aide de camp of the commanding general of the Second Corps” and order Eglin to appear at an “emergency staff meeting” at the McAlpin Hotel in Manhattan on January 31 or February 1 with the material. Eglin would be instructed to follow specific procedures for delivery, discuss the planned meeting with no one, and undertake no verification of these orders because the meeting was a “military secret.” The letter’s tone then turned sinister. After ensuring that Eglin was alone and had the required material, Crown would “over power him and remove [the] papers,” making “every effort to leave clues that would point to communistic perpetrators.”

A direct threat on the life of an American military officer left the British with no options. The U.S. government would have to be warned, a step that would expose the Jordan investigation and possibly end it.

The concerns of the British government were captured by Guy Liddell, a senior officer of MI5. In an aide-mémoire he prepared after an official visit to the United States in March and April 1938, Liddell wrote that the plot “could have been merely designed by this agent in order to obtain money, since if it did not materialize he would be discredited with his employers.”

He noted that “although the plan to overpower Colonel Eglin at the McAlpin Hotel, New York, appeared extremely crude, the matter could not be dismissed lightly since we [MI5] were positive that its details had been communicated by a German agent to the German Intelligence Service.”

On January 29, 1938, Colonel Raymond E. Lee, the U.S. embassy’s military attache in London, was briefed on the matter and given a paraphrased copy of Crown’s letter. Wasting no time, Lee cabled the War Department, which quickly determined that Colonel H. W. T. Eglin, the base commander, was in no danger and had received no such instructions.

Next the War Department requested FBI assistance to observe activities around the McAlpin Hotel, looking for the mysterious Crown and awaiting his telephone call to the colonel. Two weeks later, on February 14, a surprised FBI and War Department learned about Rumrich’s arrest in the blank passport scam, an event that probably would have gone unnoticed, except that a note containing details of the Eglin plot had been found in a search of his home. Under questioning by military authorities, Rumrich quickly admitted planning the document theft and the elimination of Eglin. He was turned over to the FBI on February 19, 1938.

Everyone now realized that Crown and Rumrich were the same person.

Crown’s Revelations

Confusion and surprise characterized conditions at FBI headquarters and the Department of Justice upon learning of Rumrich’s arrest for espionage. FBI director J. Edgar Hoover, who was vacationing in Miami, was unaware of the case and was reluctant to get the FBI involved. Attorney General Homer Cummings, like Hoover, knew nothing of the arrest and ordered an immediate damp on all news releases concerning the investigation.

A stickler for clear lines of authority and responsibility, Hoover abhorred the messy jurisdictional issues this case presented. In his view, it was already seriously flawed because of the complete absence of coordination among the State Department, War Department, FBI, New York City Police Department, and British Security Service.

The espionage charges would surely be dismissed for lack of merit, and Rumrich would end up facing only the charge of desertion. Despite pressure from the War Department to pursue the matter because of the threat to Colonel Eglin, Hoover continued to resist. He argued that the case was already in the hands of the Department of State; leaks by the New York City Police Department to the press had compromised the case, reducing the chances of a successful prosecution; and little could be achieved because the conspirators were now undoubtedly aware of the ring’s exposure.

In the end, Hoover relented to military pressure, and Rumrich’s prosecution for espionage and for impersonating Hull was authorized by U.S. attorney Lamar Hardy.

Leon Turrou, a thirty-eight-year-old, ten-year veteran working in the FBI’s New York field office, was assigned to the case. Turrou was chosen because of his previous experience with the attempted sabotage of the navy dirigible the USS Akron by a fanatic Communist and because of his fluency in German, Russian, French, and Italian.

Leon Turrou, a thirty-eight-year-old, ten-year veteran working in the FBI’s New York field office, was assigned to the case. Turrou was chosen because of his previous experience with the attempted sabotage of the navy dirigible the USS Akron by a fanatic Communist and because of his fluency in German, Russian, French, and Italian.

Turrou started the investigation with a series of illuminating interviews with a talkative Rumrich that soon revealed the vast extent of the Abwehr spy network in the United States. Details about how Rumrich had begun spying, his methods of keeping in contact with his Abwehr masters in Europe, leads to other spies in the United States and Canada, and a catalog of his successes and the ease with which he was able to obtain military and government secrets all cascaded out in rich detail.

The chatty spy, hoping to save himself, outlined Abwehr methods for passing on instructions, receiving messages, and checking on agents around the World. He identified Karl Schleuter, then in Germany and a steward on the steamship the SS Bremen, as the courier who had carried his information to Germany.

Once on the Abwehr payroll, Rumrich had learned that Otto Maurer, an official of the Hamburg-America Steamship Lines, had placed the original advertisement in the New York Times signaling German interest in Rumrich. Maurer acted on instructions from a Kapitan-Lieutenant Dreschel, assigned to the office of the marine superintendent of Hamburg-America, and Dreschel’s orders came from Captain Heinrich Lorentz, chief officer of the German cruise ship Europa, which made weekly crossings of the Atlantic Ocean between Europe and the United States.

Maurer, Dreschel, and Lorentz answered to Erich Pfeiffer, an Abwehr intelligence officer assigned to Bremen, Germany. Messages and packages between Rumrich and Pfeiffer were carried by ordinary crew members, particularly Schleuter. Sending and receiving mail and packages from mail drops was an alternative method of communication designed to enhance the security of the operation. Jordan’s address in Scotland was not Rumrich’s only mail drop; he also used two addresses in Germany supplied by his superiors.

After further questioning by Turrou, Rumrich revealed the identities of two people he had tried, unsuccessfully, to recruit as spies: a U.S. Navy Department employee with access to code and cipher information, and a seaman in Newport News, Virginia.

He was more successful, however, with Erich Glaser, an army private assigned to the Eighteenth Reconnaissance Squadron at Mitchell Field in New York, who had already supplied him with important army air force and navy codes and ciphers. Glaser’s information passed through Rumrich to Johanna Hoffmann, a hairdresser on the Europa, for transmittal to Germany. Turrou also learned that Hoffmann was due to arrive in New York City sometime in the next few days.

As for Rumrich, his twenty-one-month espionage career produced some impressive results. A stunned Turrou learned that the spy’s reports to the Abwehr had covered a broad range of useful topics.

Rumrich routinely frequented taverns and bars along the docks and wharves, casually chatting for hours with unsuspecting sailors, merchant seamen, longshoremen, and stevedores interested only in a few drinks and some relaxed conversation. In this way, Rumrich picked up an important answer to a seemingly innocuous question here, a valuable tidbit there, or an interesting piece of gossip somewhere else. When assembled and combined with his own observations, these disparate pieces of seemingly irrelevant data created a clear picture of ship destinations and descriptions, warship movement and construction, and the volumes, types, and destinations of cargoes moving in and out of the port of New York City.

Rumrich also admitted that he had stolen copies of confidential ship-to-shore communication codes, information concerning the navy’s Atlantic Fleet movements, and contingency plans for the installation of antiaircraft weapons in the New York metropolitan area. All were now hopelessly lost to Germany.

Greibl

A search of Rumrich’s home uncovered the names of Ignatz Greibl and Willy Lonkowski. Rumrich acknowledged that in May 1936, after his initial meeting with the Abwehr courier who signed him up, he had been introduced to both men, whom he characterized as key agents in the Abwehr’s U.S. operations.

A search of Rumrich’s home uncovered the names of Ignatz Greibl and Willy Lonkowski. Rumrich acknowledged that in May 1936, after his initial meeting with the Abwehr courier who signed him up, he had been introduced to both men, whom he characterized as key agents in the Abwehr’s U.S. operations.

Turrou then interviewed Greibl and learned that he was a physician, born, raised, and educated in Munich, who had immigrated to the United States in 1925. Supported by his wife, Maria, a nurse he had met while serving in the German army, Greibi continued his medical studies at Long Island Medical College and later at Fordham University.

He started a medical practice in Bangor, Maine, and later moved back to New York City, settling in the Yorkville section of Manhattan. A much more difficult interrogation subject than Rumrich, the wily physician cleverly deflected Turrou’s direct questions about espionage, claiming that he was merely a doctor dedicated to the needs of his patients. With no admissions by Greibl, Turrou was forced to let him go.

What Greibl did not tell Turrou was that he was the linchpin of the whole organization.

Less than halfway into President Franklin Roosevelt’s first term in office, Greibl wrote a personal letter to Joseph Goebbels, Hitler’s minister of propaganda, offering his services to the Reich. Like Rumrich’s letter, Greibl’s offer eventually found its way to the Abwehr. Within months, an agent assigned to a ship crew met Greibl in New York, assessed his value for intelligence collection, signed him up, and introduced him to Lonkowski.

Greibl was, in Rumrich’s opinion, a true German nationalist, an immigrant so heartened by the success stories coming out of Germany that he wanted to make a personal contribution to his native land. This passion led him to join the German Society of Literature and Arts in the United States and to assume a leadership role in a New York pro-Nazi organization called the Friends of New Germany.

U.S. officials first encountered Greibl in 1934 when, as convention chairman, he gave the opening speech before twenty thousand German Americans at a swastika-clad Madison Square Garden on German Day. He roused the audience with fiery rhetoric demanding that U.S. political leaders increase German representation in the government so that “within ten years all government offices will have Germans in them.” At the end of his remarks he thrilled the screaming listeners by announcing that he would immediately send a cablegram to the “Great Awakener of the German people,” referring to Hitler, pledging the audience’s loyalty.

The Yorkville section of Manhattan was one of the largest German colonies in the United States at the time, and German American physicians were a rare commodity. The high status accorded to Greibl in the community allowed him exceptional access to information that was not available to the average person.

German immigrants living in the area preferred his medical services because he spoke their language, had a similar background and common cultural experiences, and shared their sense of pride over the successes of the new Germany. The strong doctor-patient bond contributed to patients’ willingness to discuss personal issues that they would be unlikely to confide to an American doctor. Dr. Greibl exploited this relationship and gently pried into the private lives of his patients without raising any suspicions.

Taking medical histories could prove very productive. Information about a patient’s job, place of employment, capacity to pay medical bills, and, most important, attitudes, feelings, and loyalties toward Germany and the new Nazi leadership was easily elicited. Depending on the patient’s potential value to German rearmament and access to valuable military information, a decision would be made whether to risk approaching that person for recruitment into the Abwehr espionage network.

One such agent recruited by Greibl was Christian F. Danielsen, a marine engineer living in Maine. Danielsen’s forty-year residency in the United States and American citizenship were not enough to resist the lure of Greibl’s approach. He agreed to work as an agent because he had children still living in Germany and “a more than nostalgic attachment to the old country.”

Employed at the Bath Iron Works in Bangor, Danielsen soon began supplying the Germans with secret blueprints of destroyers and other warships that the company was designing and building for the navy. Every month or so, he traveled to New York and personally delivered his cache of secrets to Greibl.

In this careful yet deliberate manner, the Abwehr maintained a successful international military-industrial espionage organization with access to a wide variety of valuable technical information. The Greibl-Lonkowski ring was a diverse and highly effective group of spies that included, as one historian described it, a “Swiss born Captain in the United States Army who supplied details of new infantry weapons, a draftsman in a firm of naval architects in New York, a designer of guns in Montreal, an engineer in the metallurgical laboratory of the Federal Shipbuilding and Dry Dock Company at Kearny, New Jersey, contacts in the navy yards in Boston, and Newport News, Virginia and in a number of scattered aircraft factories.”

With the U.S. government oblivious to these losses between 1934 and 1940, the Abwehr’s U.S.-based agents filched a steady stream of the latest technical advances coming off the industrial drawing boards. To illustrate the magnitude of these losses, one need only examine the period between January and July 1935.

During these seven months, Abwehr agents delivered into German hands:

- the plans for every plane built at the Sikorsky aircraft plant in Farmingdale, New York;

- blueprints for the FLG-2 and the SBU1 carrier-based scout bomber under production by the Vought Company for the U.S. Navy;

- specifications for a bomber manufactured by the Boeing Company;

- a plane produced by the Douglas Aircraft Corporation

- assorted classified U.S. Army maps

- details of an anodizing process and certain military-related experiments with chromium

- blueprints for three new navy destroyers

- communication devices manufactured by the Lear Radio Corporation

- reports on tactical exercises being conducted by the navy at Mitchell Field in New York

Lonkowski, Gudenberg, and Voss

The focus of the Rumrich interviews turned next to Lonkowski. Born in Silesia before the turn of the twentieth century, Lonkowski had been educated in German technical schools and served in the German army as an aircraft mechanic during the First World War. He held occasional postwar jobs in Germany’s tiny aircraft industry before reentering the army, where his talents were quickly spotted by German military intelligence.

As one of the few persons knowledgeable about airpower, his ability to move about Europe, studying foreign aircraft development, became critical. In 1922 he traveled to France using an alias to assess the state of aviation development there and returned to Germany with a large cache of valuable information. That success led to other foreign intelligence assignments and eventually to his most important Abwehr mission.

In 1927, with a false passport and a new alias, Lonkowski was ordered to the United States to steal U.S. aircraft industry secrets. Topping the German wish list were new and more efficient airplane motors under commercial development and new propeller designs being tested by the Westinghouse Corporation.

After settling into a routine in the United States, Lonkowski was surprised to discover a benign counterintelligence environment. Government agents never questioned him, never inquired about his personal history, and showed no interest in his associates, his loyalties, or his comings and goings. In general, he found American industrial conditions rather inviting for an experienced, cautious, and enterprising spy.

Lonkowski’s aircraft technical skills were in great demand, and with no background investigation to worry about and no industrial security procedures in place to determine employee suitability, he soon obtained an entry-level technical position at the Ireland Aircraft Corporation on Long Island. His good work habits and common sense soon caught the attention of Ireland management, leading to a promotion to the personnel department, where he took control of the hiring and firing of workers. This allowed Lonkowski to plant two other Abwehr agents, whom he had recruited before leaving Germany, at the Ireland Corporation.

Werner Georg Gudenberg and Otto Herman Voss reached the United States in 1928 and, thanks to Lonkowski, immediately started working at Ireland. However, three spies at the same location were unnecessary, so the small espionage ring gradually expanded.

Werner Georg Gudenberg and Otto Herman Voss reached the United States in 1928 and, thanks to Lonkowski, immediately started working at Ireland. However, three spies at the same location were unnecessary, so the small espionage ring gradually expanded.

Thirty-three-year-old Gudenberg, a World War I veteran of the German army, obtained work at the Curtiss Airplane and Motor Company in Buffalo, New York. Curtiss was conducting experimental research on lightweight aluminum airframes at the time.

Voss, also thirty-three, had served in Finland and France during the war. After the armistice he spent another two years in the volunteer corps of the German army, followed by attendance at a technical school until 1922. He eventually settled in Baltimore, Maryland, where he worked for the Seversky Aircraft Company manufacturing airplane propellers for the U.S. Navy.

Gudenberg and Voss sent their stolen military secrets to Lonkowski, who packaged them for transatlantic shipment via courier to Berlin. The success of this efficient little ring was remarkable. It had smuggled volumes of sensitive technical data to Germany by 1932, including the design for a “fireproof plane” and “the world’s most advanced power air-cooled motor” under development for the army by the Wright Aeronautical Corporation. Also stolen were plans for a “pursuit plane said to be capable of ‘landing either on a ship or on water’ that were still on the drawing boards of the, Curtiss Aeroplane and Motor Company.”

Having successfully completed his mission, Lonkowski was anxious to return home to Germany. He was set to sail for Europe on September 27, 1935, when he was detained by U.S. Customs Service officers, who had discovered material in his bags suggesting his involvement in espionage. Lonkowski was later released and returned to his home on Long Island when the documents were deemed to be inconsequential. Before authorities could get wise to his activities, Lonkowski contacted Greibl, who wasted no time taking him to Canada, where he anonymously boarded another ship bound for Europe.

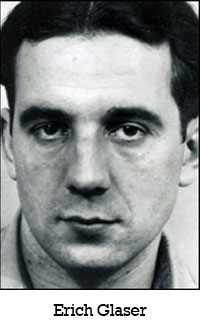

Glaser

Erich Glaser became the next focus of Turrou’s attention. Born in 1909 in Leipzig, Germany, he immigrated to the United States in 1930 and joined the army fifteen months later. His military service record included a stint in the Panama Canal Zone, reenlistment in 1934, and another three years in the Philippines until his discharge in 1937. After only a short time as a civilian, Glaser reenlisted in January 1938 and served in the air corps at Mitchell Field until his arrest.

Erich Glaser became the next focus of Turrou’s attention. Born in 1909 in Leipzig, Germany, he immigrated to the United States in 1930 and joined the army fifteen months later. His military service record included a stint in the Panama Canal Zone, reenlistment in 1934, and another three years in the Philippines until his discharge in 1937. After only a short time as a civilian, Glaser reenlisted in January 1938 and served in the air corps at Mitchell Field until his arrest.

Glaser and Rumrich originally met in the Panama Canal Zone, and he later lived with Rumrich and his wife for a time in the Bronx. As noted earlier, Rumrich identified Glaser as one of his agents and provided a full description of his espionage-related thefts. Faced with accusations of supplying highly sensitive cipher and code data to the Germans, Glaser made a complete confession.

Hoffmann

Ten days after Rumrich’s arrest, Johanna Hoffmann, the hairdresser-courier, arrived in New York City aboard the Europa. Turrou confronted her with Rumrichs accusations along with incriminating letters addressed to Greibl found during a search of her belongings. Alone and trapped, Hoffmann too admitted spying for the Germans and described her role as a courier, carrying military secrets between Greibl and her intelligence bosses in Germany and delivering messages, money, and instructions on her return to the United States.

Ten days after Rumrich’s arrest, Johanna Hoffmann, the hairdresser-courier, arrived in New York City aboard the Europa. Turrou confronted her with Rumrichs accusations along with incriminating letters addressed to Greibl found during a search of her belongings. Alone and trapped, Hoffmann too admitted spying for the Germans and described her role as a courier, carrying military secrets between Greibl and her intelligence bosses in Germany and delivering messages, money, and instructions on her return to the United States.

She identified other crew members doing spy work and defended her activities, explaining that refusal to assist the Abwehr would have meant the loss of her job. Another letter found in Hoffmann’s belongings was traced to one of Lonkowski’s agents, Otto Voss.

Having returned from Baltimore to the New York area, Voss was now working for the Sikorsky Airplane Company in Farmingdale. Turrou quickly located and interrogated Voss, who admitted his involvement in the spy ring and implicated additional participants, including Lonkowski and Carl Eitel, both of whom were safely in Germany.

At the end of World War II, Eitel found himself interned at Camp 020 in England, where he was interrogated by British officials. His revelations offer insights into the Abwehr recruitment of German citizens for espionage.

Eitel was born in Mulhouse, Germany, in 1900 and joined the German army toward the end of the First World War. Later as a civilian he held various midlevel hotel service positions in Germany and France before signing on as a wine steward aboard the Norddeutsche- Lloyd Lines’ SS Bremen in 1928. Promotion to chief wine steward in the ship’s Ritz Carleton Grill Room soon followed.

In the spring of 1930, Eitel was approached by a stranger aboard the ship who asked the steward to pick up some magazines, technical journals, and newspapers for him the next time he visited the United States. After months of collecting this material for the man, Eitel was given a “typewritten list of magazines, newspapers, and books which were more urgently required by his people.” Included on this list were commonly available periodicals such as Popular Mechanics, Popular Science, and the Army and Navy Journal, which, Eitel later told his interrogators, were of interest to the Germans “since they disclosed advance information on technical developments in many spheres.”

Fully aware that he was being used to collect low-level intelligence, and seeing no harm in it, Eitel continued to follow orders. He even joined the Nazi Party and became a member of the Bremen’s political cell led by Wilhelm Boehnke, who held the rank of Orstgrupenfuhrer. The power of this position was clearly displayed when Eitel observed Boehnke, the ship’s baker, summon the captain to his cabin for a confidential discussion.

Gradually the demands on Eitel shifted from acquiring publicly available magazines and journals to obtaining sensitive information bordering on espionage. Military fortifications and installations around the ports of Cherbourg and New York City—including commercial ship movements; types and numbers of aircraft, airfields, and seaplane bases; and warship movements—became Eitel’s new targets.

Realizing that his continued employment depended on his cooperation with the Abwehr, he later told his British interrogators that he reluctantly agreed to the new demands and set about acquiring the information through observation, conversation, and the purchase of public source material.

On one trip home, Eitels’ contact introduced him to Erich Pfeiffer, head of the Abwehr’s Bremen station. After commending him on his success, Pfeiffer issued new orders: on future visits to New York, Eitel was to make every effort to “establish some contact . . . with an individual either serving in the U.S. Navy or having some indirect connection with it.” Filled with dread, Eitel reluctantly accepted this new assignment because, as he told his interrogators, turning Pfeiffer down would have cost him his job.

Collecting magazines and newspapers was one thing, but trying to convince Americans to spy on their country was a dangerous undertaking that he was neither equipped nor trained to do. Owing to fear, lack of skill, or both, Eitel never recruited an American spy. However, by 1935 he routinely carried messages, orders, and stolen secrets between Greibl, Lonkowski, Voss, and Gudenberg in New York and Pfeiffer in Bremen.

Greibl Reappears

A few weeks later, concerned about what government investigators were learning about the spy ring and his role in it, Greibl appeared, unannounced, at the New York office of the FBI. Hoping to ingratiate himself with his interrogators, he began volunteering details of German espionage in the United States, his role in the conspiracy, and the structure and personalities of the setup.

He began by describing the Deutsche-Americanische Berufagemeinschaft (DAB), the principal German bund organization in the United States. Originally an organization of German white-collar workers, the DAB was, in fact, a branch of the German Labor Front, which supervised practically all labor and professional associations in Germany.

He also offered details surrounding the 1937 visit to the United States of Frederick (“Fritz”) Wiedemann, a wartime comrade of Hitler and one of his three personal adjutants. The ostensible purpose of the trip was sightseeing and visiting old friends, but according to Greibl, Wiedemann’s real mission was to meet with Fritz Kuhn, the leader of the German-American Bund. Wiedemann tried to dissuade Kuhn from demanding that German citizens living in the United States give up membership in the German-American Bund, which, in Greibl’s view, constituted a large percentage of the organization’s steadily increasing membership.

Professing complete innocence, yet faced with the collective accusations of Rumrich, Voss, Hoffmann, and Glaser, who identified him as the ring leader, Greibl slowly began conceding some involvement.

“[I] never had anything to do with espionage activities,” he told Turrou, “although certain curious circumstances had brought [me] in contact with a number of other people who appeared to be doing some work of the kind.” The more he talked, however, the more the particulars of his spying activities emerged.

He provided additional details of Voss’s espionage thefts, as well as the loss to German agents of valuable information from Kallmorgen Optical Company in Brooklyn, New York; Gibbs and Cox, a naval architecture company, and Sperry Gyroscope Company, both in New York City; and an unnamed shipbuilding company in Newport News, Virginia.

Next, he identified a civilian naval employee named Agnes Driscoll, a woman unknown to the FBI, who had sold a “secret decoding device” to Germany for $7,000.

The more he talked, the more Turrou suspected that, just as Rumrich had reported, Greibl was in fact the head of German military intelligence collection in the United States. Confronted with these suspicions and the FBI’s awareness of his 1934 letter offering his services as a spy, Greibl prevaricated, evading direct responses while minimizing his involvement with partial and misleading admissions.

Finally, Greibl acknowledged his assistance to German intelligence but claimed that it had only begun in January 1937, when he had sailed to Europe aboard the Europa with his mistress, Kay Moog. Karl Schleuter, the ship steward, had introduced him to Kapitan-Lieutenant Menzel and another crew member named von Bonin, and only later did he learn that both were Abwehr officers. Von Bonin was particularly interested in Moog, whom he brazenly encouraged to move from her home in New York City to Washington, D.C., rent an apartment there, and “become acquainted with various government officials from whom she would extract information.”

Further FBI questioning produced the names Karl Weigand and Karl Frederich Wilhelm Herman, the latter perhaps the most important conspirator identified by Greibl. Herman, as head of “the Gestapo in New York,” would be available to assist Greibl whenever he was needed.

Greibl found himself trapped by his own admissions and the growing mountain of evidence against him. Facing arrest, conviction, and a lengthy imprisonment, he began stalling for time to plan his next move. Securing the chief FBI investigator’s trust by offering his assistance in the investigation was Greibl’s only option, and the gullible Turrou accepted.

Under Turrou’s direction, Greibl learned details from Herman about German espionage in the United States, including that “Weigand” was a fictitious name for Theodor Scheutz, a steward aboard the Hamburg-America Lines’ SS New York. Greibl also met with Dreschel of Hamburg-America, and their conversation, electronically recorded by the FBI in a New York City hotel room, produced even more information.

Rumrich’s arrest in February 1938 shocked the Abwehr, forcing a temporary halt to its transatlantic courier operations. Scheutz, at sea aboard the SS New York, abruptly left the ship at Havana, Cuba, after receiving a telegram from Germany warning him of the arrest.

A search of Herman’s residence produced a large cache of incriminating evidence, including the names of Rumrich and Voss. Armed with Greibl’s evidence against Herman and Dreschel, Turrou interviewed both men, and they quickly confessed.

Herman described his role and furnished the names of additional persons cooperating with the German intelligence services. Like Eitel, he too claimed that the Abwehr had forced him to cooperate and that failure to obey instructions would have meant the immediate loss of his job.

Turning on Herman, Dreschel told his interrogators that he had been required to issue special passes in “very exceptional cases” that allowed the holder to board any German ship and gain access to any crew member after immigration officers had departed, permitting the safe acquisition and transmittal of secret information destined for Greibl or Germany.

Dreschel had also been ordered to allow Greibl to use Norddeutsche-Lloyd Lines’ telegraph system for communicating with Pfeiffer in Bremen, and Dreschel’s ship had been used to smuggle Abwehr agents in and out of the United States.

One such instance involved the hasty departure of a person named “Spanknoebel,” whom Dreschel described as the principal organizer of Nazi groups in the United States. He then ran off a list of German agents in the United States that included Wilhelm Boening, a machinist and New York resident, and Johann Baptiste Unkel, a spy who had already supplied the Abwehr with complete plans of military fortifications in the Panama Canal Zone.

Boening was described as the head of the Ordnungsdienst, a uniformçd Nazi militia group made up of about twenty thousand Americans of German origin, which conducted military-type drills throughout the United States.

Collapse

Success followed success as Turrou, with seemingly no effort, gained admissions from practically everyone he interviewed. In the ninety days since the Rumrich arrest, he had assembled volumes of information concerning German espionage in the United States; spies were being identified on an almost daily basis, along with full descriptions of the huge quantities of military and industrial secrets lost to Germany.

Turrou then made a tactical decision that drastically altered the direction of the case and created an unexpected publicity nightmare and public policy debacle for the FBI and the U.S. government.

Since joining the FBI ten years earlier, Turrou had served in a number of field offices and investigated a variety of criminal matters, including some high-profile cases. For instance, Turrou had found the ransom money paid by Charles Lindbergh in the kidnapping of his son in Bruno Richard Hauptmann’s garage. Later, at Turrou’s urging, Hauptmann had provided incriminating handwriting samples that were compared with and matched to the ransom note.

Turrou was also assigned to investigate the machine gun slaying of gangster Frank Nash, two police officers, and an FBI agent outside the Kansas City train station on the morning of June 17, 1933—a shooting that became known around the world as the “Kansas City Massacre.”

Turrou’s experience did not equip him, however, to understand foreign intelligence methods or the investigation of espionage. He approached the German spy ring case like any conventional investigation.

After assembling all the facts, he began informing the suspects that a grand jury would be convened on May 5, 1938, to examine all the charges and that each of them would be served with a subpoena, requiring their appearance to give testimony. When that date arrived, both FBI director Hoover and Lamar Hardy, the U.S. government’s chief prosecutor in New York, were dismayed to learn that fourteen of the eighteen identified ring members had fled the country. The four who remained were those originally jailed in February. U.S. officials should not have been surprised; both Hoover and Turrou knew from Dreschel’s admissions that German shipping lines and crews were under Abwehr orders to facilitate the escape of agents who found themselves in trouble.

Gudenberg, Lonkowski’s agent, escaped prosecution by stowing away on the Hamburg-America Lines’ SS Hamburg, leaving a wife and child in the care of his brother-in-law in Bristol, Pennsylvania. Greibl turned up safely in Germany, where he publicly accused Turrou of misinforming him about the date of the grand jury, claiming that it had been rescheduled for May 12, 1938. Both Greibl and coconspirator Karl Schleuter stowed away on the SS Bremen, which departed for Germany on May 11, 1938; neither man ever returned to the United States.

The initial success of the Rumrich-Greibl espionage investigation suddenly collapsed into a huge publicity disaster for the FBI’s bumbling counterspies. The New York press laid the blame for the escape of the fourteen fugitive spies on Hoover’s doorstep.

Under the Roosevelt administration, Hoover and the FBI had skyrocketed to national fame. The federalization of crime fighting had thrust the Bureau into the American consciousness with headline-grabbing solutions to thousands of cases, including the kidnappings of prominent Americans, bank robberies, and extortion, not to mention the capture of glamorous fugitives. Hoover and his agents pursued scientific law enforcement and had achieved a national stature; they conveyed a polished image and the message that there was no crime the FBI could not solve.

Now, behind the scenes, a different reality was unfolding. In spite of the mounting evidence of foreign espionage the Bureau had collected, FBI officials were acutely aware of how badly they had mishandled the case.

Doctrine that had worked so successfully in the war against fugitives, bank robbers, and embezzlers during the 1930s had failed in this case. The FBI was now up against a very different investigative problem.

With suspects disappearing and major newspapers serving up a daily dose of criticism, the staff at FBI headquarters began instituting efforts to better inform Special Agents in Charge (SACs) about this new criminal phenomenon, as well as rank-and-file investigative agents. New training methods were needed, and it was hoped that this could begin with a nationwide SAC conference planned for the summer of 1938.

One FBI official, in an internal memorandum, described the new and unexpected challenge facing the FBI.

This new adversary was “shrewd and cunning.” Unlike the motivation of homegrown criminals, the goal of espionage agents was to assist “their native land,” rather than the “financial remuneration obtained.” As a consequence, “the investigation of an espionage case presents, to some extent, a different type of problem than is ordinarily encountered in other cases investigated by the Bureau.”

No less a figure than Reed Vetterli, SAC of the FBI’s New York office and Turrou’s boss, weighed in on the Bureau’s poor performance. Vetterli was an experienced investigator and no stranger to major cases. He had moved up quickly through the ranks, working many cases throughout the country. In June 1935, serving as SAC of the Kansas City FBI office, he had been wounded during the Kansas City Massacre and later testified at the trial of the triggerman, Adam Richetti.

The thirty-four-year-old Vetterli did not mince words in his critique of the FBI’s performance, calling it a “rather feeble” effort consisting mainly of interviews and interrogations, followed by more interviews and interrogations. Such “precipitous” actions, he noted, seriously disadvantaged FBI investigators.

They had acted only on what an interviewee knew or was willing to disclose, while at the same time providing the suspect with more information about the investigation than he originally knew. In effect, the FBI had relied mainly on the word of one suspected spy who turned on a co-conspirator, rather than employing a full array of investigative tools to produce independent, verifiable evidence that could be used in court.

Espionage agents, in Vetterli’s view, were smart enough “to become citizens of the U.S. and claim allegiance to this country, when in reality. . . in a number of instances, this is all a sham and artifice and merely an effort to further allay our suspicion with respect to them.”

Then, risking the wrath of FBI headquarters for his honesty, he warned his Washington bosses that the German agents investigated in the Rumrich case had little regard for FBI prowess and “probably have laughed time and again at our efforts in connection with the instant case.”

For Hoover, 1938 was not shaping up as a banner year. In February personal tragedy struck when his mother, Annie, whom he had lived with and cared for since joining the Department of Justice twenty-one years earlier, suddenly died. Now the FBI’s first big espionage case, which had begun with such promise, was threatened with dismissal because Hoover’s chief investigator had allowed fourteen of its principal subjects to escape right under his nose.

And the loss of the spies was only the start of Hoover’s nightmare. Adding to his woes was the embarrassing public revelation in June that Turrou had been dismissed from the FBI “with prejudice.” The charge: violating the “G-man oath which binds all agents not to disclose any service information.”

Hoover learned that Turrou had been leaking information about the investigation to New York newspaper sources and had drafted a series of articles about the case for publication in the New York Post. Turrou’s treachery infuriated Hoover, particularly because it violated a nondisclosure agreement the agent had signed years earlier upon entering FBI service. While the New York media frenzied over the flap, Hardy sought a court order enjoining the press from publicizing what one paper called the “authentic inside story” by the FBI’s “former star G-man.”

Hoover learned that Turrou had been leaking information about the investigation to New York newspaper sources and had drafted a series of articles about the case for publication in the New York Post. Turrou’s treachery infuriated Hoover, particularly because it violated a nondisclosure agreement the agent had signed years earlier upon entering FBI service. While the New York media frenzied over the flap, Hardy sought a court order enjoining the press from publicizing what one paper called the “authentic inside story” by the FBI’s “former star G-man.”

For his part, Turrou challenged Hoover, denying that he had ever signed a nondisclosure agreement and claiming that he had every right to use information derived from an ongoing federal investigation for his own purposes. Simon Rifkind, Turrou’s attorney, accused the government of a double standard concerning the publication of information about criminal cases, offering as evidence a book of “clippings from every newspaper in the city” and claiming that “one of the most prolific sources of news contained in these clippings was J. Edgar Hoover, who was Mr. Turrou’s Chief.”

Adding to this already lively controversy were new accusations about Turrou and, by inference, the FBI during the ongoing prosecution of the four spies still in custody. George Dix, the attorney for Johanna Hoffmann, accused Turrou of accepting a bribe from Greibl in exchange for helping him slip out of the country—an accusation that Turrou was later forced to vigorously deny in a sworn affidavit.

The Rumrich fiasco soon took on national proportions, making its way directly to the Oval Office. President Roosevelt had no choice but to weigh in on the matter when J. David Stern, publisher of the New York Post, sent him a letter on June 23, 1938, accusing the Department of Justice of muzzling the press and conspiring with his competitors to prevent the publication of Turrou’s articles.

“Rival newspapers and certain other interests,” Stern warned the president, “have persuaded the Department of Justice to hold up the publication of a series of articles on Nazi espionage in this country.” Yet in his opinion, “all of the important facts already have been printed in all newspapers. The specious plea has been presented that publication of these articles might obstruct justice.”

Speaking to a group of reporters in the Oval Office the next day, the president roundly criticized the press and, by implication, Stern, for their behavior in such a sensitive matter. Accusing the newspaper of questionable “patriotism and ethics” for signing a contract with Turrou, a “government employee” with access to privileged information garnered strictly through his work as a FBI agent, the president denounced the publication of the details of the case before a grand jury or a trial jury had heard the evidence .

With the press screaming and the principal espionage suspects now in Europe, the Department of Justice and U.S. attorney Hardy took steps to repair some of the damage.

In May, Hardy issued material witness arrest warrants for Boehnke, who had recruited Kay Moog, as well as couriers Walter Otto, Lutz Leiswitz, Johann Hart, and other ship crew members. Unfortunately, all of them had already fled to Europe.

On June 2, 1938, the FBI arrested Heinrich Lorentz, captain of the Norddeutsche-Lloyd liner Chemitz, and Frans Friske, former captain of the Hamburg-America liner Hindenburg. Both were charged as material witnesses to espionage and jailed. By the next day, both had been released on $2,500 bail and soon escaped to Europe by ship, prompting Hoover to publicly point the finger of blame at Hardy for their disappearance.

With the flight of Greibl, Gudenberg, Schleuter, Friske, Lorentz, and at least fourteen suspected agents, and with the successful prosecution of the few remaining suspects in jeopardy, Hardy decided on a desperate new tactic. He ordered the arrest of Maria Greibl, the doctor’s wife, as a material witness, just as she was preparing to leave the country to join her husband in Germany. Having exhausted all options, but with no credible evidence against her, Hardy hoped to use her detention as leverage to prompt her husband’s speedy return to the United States.

But if Hardy thought that Mrs. Greibl, who was no stranger to controversy, would sit quietly in jail, he was badly mistaken. Five years earlier, George Medalie, then U.S attorney for New York, had ordered her to appear before a grand jury to explain why a certain German, who had come to the United States to organize support for Hitler, had been a house guest of the Greibls. She had brazenly refused, claimed that she was innocent of any wrongdoing, and publicly charged that she could not expect unbiased treatment from Medalie because he was Jewish.

Mrs. Greibl showed the same grit this time. Claiming bewilderment over the accusations of spying, she announced publicly that her husband was an innocent man who had gone to Austria on family business and would return to the United States within the next three weeks. She summoned reporters to her jail cell and told them that her arrest was actually a “frame up by his [Dr. Greibl’s] enemies,” vowing that “nothing could turn [her] against him.” She then portrayed herself as a victim of Hardy’s incompetence and cruelty. In response to questioning, she told reporters that Dr. Greibl had been “hounded” by investigators and then speculated that if he were, in fact, in Germany, “there is no safer place for him.”

The publicity disaster for Hardy and Hoover continued when Seward Collins, editor of the America Review, joined the fight on Mrs. Greibl’s behalf. Collins, a power in the New York publishing world, took on the Roosevelt administration directly by accusing the government of holding the doctor’s wife “hostage” in its efforts to force his return to the United States—a practice that was tantamount to “torturing the relatives of accused persons as in Stalin’s Russia.” With an eye toward getting Mrs. Greibl’s exclusive story, Collins secured her release from jail by personally putting up $50,000 bail on June 11, 1938. Collins was soon disappointed, however, for within days of her release, she too skipped bail and quietly boarded a ship bound for Europe.

The Trial

The trial of the three remaining conspirators (Rumrich had already pleaded guilty)—Otto Voss, Erich Glaser, and Johanna Hoffmann—began on October 18, 1938, in the Federal Court Building in Manhattan and was front- page news for the next three days.

Voss was charged with sketching and supplying information on the construction of aircraft wings, fuel and gasoline compartments, and bomb racks built at the Sikorsky Airplane Corporation in Farmingdale, New York.

Hoffmann was accused of serving as a courier, transmitting “restricted code used for communication between military aircraft and its station.” Glaser was charged with providing army and navy radio telephone-telegraph procedure manuals to the Abwehr.

Insights into FBI knowledge of the extent and nature of German espionage in the United States acquired since the arrest of Rumrich can be gleaned, in part, from the testimony of witnesses during the trial.

Hardy gave the opening statement for the government and accused Hoffmann, Toss, and Glaser of enabling the “far-seeing eye” of the German government to infiltrate U.S. military and industrial research centers. After outlining the techniques used by the ring to steal information, he laid out for the jury the clever methods used to smuggle those secrets out of the country through couriers aboard transatlantic ships.

The prosecution’s first witness was Guenther Rumrich, who had made a deal with the government in exchange for his testimony. With rich detail, Hardy’s star witness explained to a packed New York courtroom how he had volunteered his services to the Abwehr and the elaborate steps taken to contact him and sign him up as an agent.

The jurors learned that Rumrich had been ordered to obtain genuine White House stationery so that it could be taken back to Germany and used to forge fictitious presidential orders requesting copies of the blueprints of the Enterprise, the country’s newest aircraft carrier.

The important role of shipboard agents was also explained to the enthralled jury. Their duties were not limited to carrying secrets back and forth across the Atlantic; these German agents also opened sealed transatlantic mailbags using sophisticated techniques. Each piece of mail underwent careful examination, and any information of value was recorded and passed on to German military and political planners. The letters and packages were then resealed so that the recipients would be unaware that any tampering had occurred.

Led by Hardy’s careful questioning, Rumrich testified that his intelligence chief often bragged that the Abwehr had spies in all U.S. aircraft plants and that their list of achievements was extensive. Among the information obtained were a navy signal code used to communicate between the fleet and land batteries, the number of coast artillery regiments stationed in the Panama Canal Zone, secret and confidential military booklets, the army mobilization and defense plans for units on the East Coast of the United States, and much more.

The two month trial had its humorous moments. In another stinging jab at the FBI’s already sagging counterespionage reputation, the German government arrogantly dismissed any concern over the matter, claiming that the Americans themselves had little concern. A German foreign ministry spokesman publicly claimed that his government viewed the entire issue with “equanimity,” adding that the Americans have no great enthusiasm over the spy case because the very man who dug up the information on which the charges were based since has tried to sell his story for publication (referring to Turrou).

Next it was George Dix, Hoffmann’s attorney, who went after the FBI and Turrou. He called the already discredited agent to testify as a defense witness. Dix’s strategy was to cast his client as the victim and Turrou as the overreaching government investigator interested only in enriching himself from the sale of his story. Under withering and often embarrassing questioning, the former FBI agent was repeatedly forced to defend himself against accusations of conducting flawed investigations, tampering with witnesses, and accepting bribes from Greibl.

If this did not leave Turrou sufficiently demoralized, Dix had one more trick up his sleeve. After finishing with Turrou, Hoffmann’s attorney surprised the packed courtroom by calling a new witness to the stand to attack the former FBI agent’s credibility. This witness offered no new information that was relevant to the case but stunned everyone by publicly accusing Leon Turrou, the FBI’s star G-man, of being an impostor. The witness testified that he knew Turrou as “Leon Petrov.”

Furthermore, before the First World War, the man he knew as Petrov had undergone treatment in the psychiatric ward at Kings County Hospital in New York City Then, with Turrou’s accuser sitting in the witness chair and his chilling accusations still hanging in the air, the trial judge, over Hardy’s vigorous objections, allowed Dix to enter Petrov’s psychiatric file into evidence. Summoning his finest theatrical skills, Dix then read aloud many of the file’s most sensational details, making certain that he emphasized Petrov’s final diagnosis as “undifferentiated depression.”

After six weeks of testimony, 3,500 pages of transcripts, and the introduction of 195 evidentiary exhibits, the three hapless German spies were convicted and sentenced to prison. Voss received the harshest sentence—a six-year term; Hoffmann got four years in prison, and Glaser was sentenced to two years.

Rumrich—perhaps the greediest, most venal, and most impulsive of the group, and the one who, in the end, brought down the ring—received a mere two years in prison in consideration for his testimony.

You must be logged in to post a comment.