The codename was “WALLFLOWER” and according to noted British military historian Nigel West, it was the “most treasured possession” of the British Security Service. When finally released to the world in 2007 after decades under lock and key in the MI-5 director – general’s office safe, World War II and Cold War historians around the world were electrified.

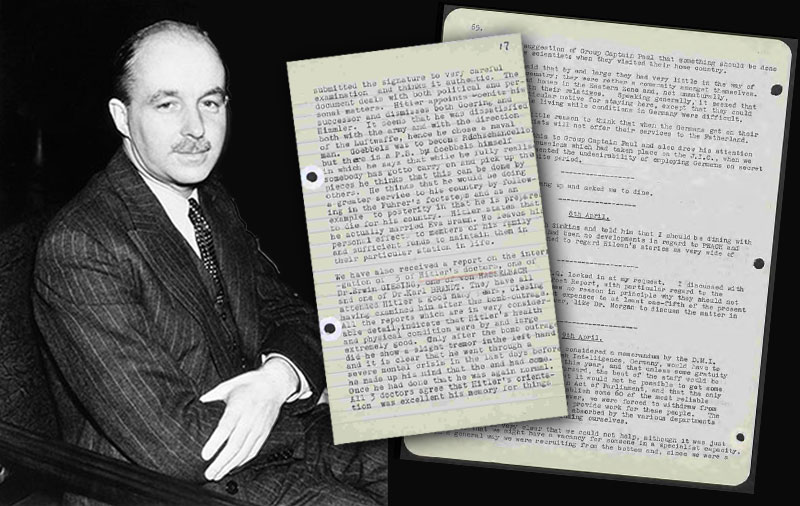

The mystery man behind this remarkable collection of personal diaries was Guy Liddell. Again, quoting West, he was “unquestionably … the preeminent counterintelligence officer of his generation.”

Guy Liddell was an Englishman born in London in 1892 to Captain Augustus Liddell, a retired army officer with the Royal Artillery. Guy and his two brothers, David, an accomplished painter and Cecil, a lawyer, were graduates of the University of Angers, a school in western France that dates back to the 11th century. All three spoke French. Guy spoke German as well. One of Liddell’s greatest pleasures was music. As a youngster he learned to play the cello, a pastime that he enjoyed throughout his life and shared regularly with friends and family at evening gatherings.

At the start of the First World War all three brothers followed their father’s footsteps by joining the Royal Artillery. Starting as privates they were soon commissioned and saw active service in France. All three would earn the Military Cross for bravery, an honor that Guy never discussed.

In 1919, he entered civilian service as a counterintelligence officer with the Metropolitan Police Special Branch at Scotland Yard. Under the direction of Sir Basil Thompson, then keen to create the nation’s first domestic security service, Liddell began investigating cases of Bolshevik subversion and Russian espionage. In 1930 he switched from Special Branch to MI5.

In 1926 he entered a disastrous marriage with Calypso Baring, daughter of Irish peer, Cecil Baring, 3rd Baron Revelstoke of Membland. The union produced three children, a boy and two girls. Calypso was a difficult personality. Her upper crust, avant garde lifestyle and penchant for lavish entertaining often proved an irritant for Guy. Dick White, Liddell’s protégé and a future director of MI5 and MI6 who knew them both, claimed that only their separation prevented Guy from strangling her. Ever true to form, Calypso later abandoned London for southern California moving in with Lorilard Baring, her half-brother.

Liddell and Calypso were a mismatch from the start. While she was flamboyant and over the top Guy was quiet and introspective. Friends and colleagues described him as thoughtful, a kind man, avuncular, with a wry sense of humor that he occasionally reveals across the pages of the diary.

Guy was the quintessential spy, in the spirit of George Smiley, John Le Carre’s classic hero. A portrait photo of him shows a somewhat distracted visage which is eminently forgettable. His longtime secretary from Special Branch and MI5 remembered him as a “rather dumpy” man, “most unsoldierly” despite his heroic wartime service. More of a listener than a talker, over his years of government service he earned growing respect from colleagues for his astute mind. Liddell, at heart a teacher, frequently lectured to government and military officials on the role of the security service. Kim Philby, a wartime MI6 colleague with whom he regularly conferred, later remembered him with affection as “an ideal senior officer for a young man to learn from.”

Liddell would never again marry. He soon abandoned the upscale London home he shared with Calypso for a more modest flat. He became more reclusive as time went on devoting much of his energy to MI5 work.

During the 1930s British intelligence produced increasing evidence of Russian and German spying in the British Isles. For Liddell this came as no surprise. When British codebreakers broke Russian ciphers revealing Moscow-inspired espionage in Great Britain in the 1920s, Liddell was part of a team that raided the offices of ARCOS, the Soviet trading office in London, then at the heart of Bolshevik spying.

In the spring of 1938, he undertook a mission to Washington at the behest of the Foreign Office for the purpose of briefing the FBI on a German spy case with ties to America and in so doing to study American counterespionage techniques. Since the end of the First World War there had been no liaison with the Americans and in particular the FBI. In Washington, he conferred with J. Edgar Hoover and members of his staff. His findings impressed in him the need for direct contact with the FBI in matters of subversion and counterintelligence. It was a theme (more of a frustration) that repeatedly surfaces throughout the diary’s war year entries. Such liaison with a MI5 representative in Washington was not to occur until after the war.

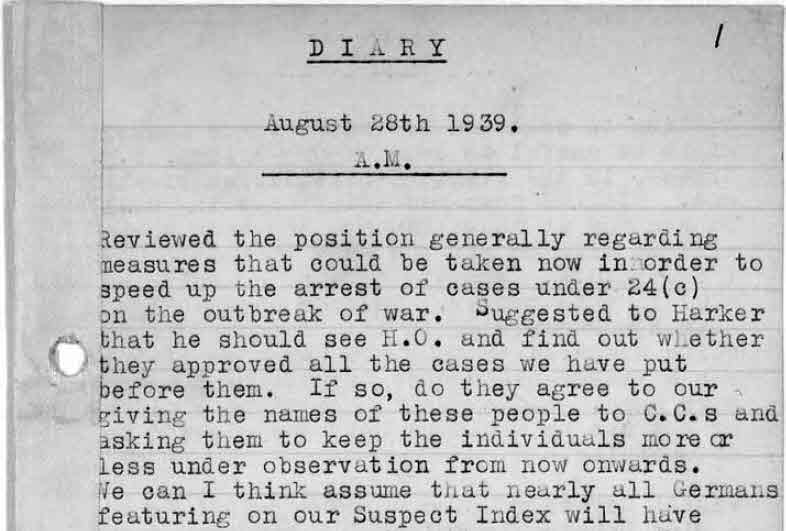

The first entry of what is simply known as the Liddell Diaries (all pages are typed for easy reading) starts on August 28, 1939 just four days before Hitler invaded Poland igniting the Second World War. Great Britain was already on a war footing with thirty – eight million gas masks having been distributed to the population and key government departments on the move away from London in anticipation of German bombing. War, in the words of one author was “inescapable.”

The journal opens with hints of what was to come. He mentions a case involving someone named “Kuchenstein,” port city security procedures, and references to prime ministerial discussions. Page after page are Chock–A–Block full of entries on matters ranging from the Double-Cross deception against the Germans, GARBO, ZIGZAG, et al., references to “Special Means” (ULTRA/ENIGMA), enemy aliens, Camp 020, “Tin-Eye” Stephens and enhanced interrogations, dealings with MI6, Censorship, refugees, other government departments and on and on and on.

It is almost creepy to know that he is constantly being stabbed in the back. Particularly, when he records meetings with the treacherous Anthony Blunt, a close and trusted friend who Liddell brought into MI5 as his personal assistant, and who later admitted that everything crossing his desk went to Moscow. We get a glimpse or two of a lesser known but equally traitorous creature linked to Guy Burgess named Goronwy Rees.

Diary entries for the post war years are in some ways more interesting. We see Liddell near the zenith of power at MI5 taking us through the Service’s early Cold War effort to cope with the new Russian espionage threat in a rapidly disintegrating British Empire. There is Philby again and the Volkov case and the Gouzenko defection with references to the mysterious “Elli” burrowed inside the British government. We meet Roger Hollis, a MI5 officer, who would rise to head the Service yet forever stained with accusations of being a Soviet mole. One later encounters Klaus Fuchs and Bruno Pontecorvo as they make their appearances as well.

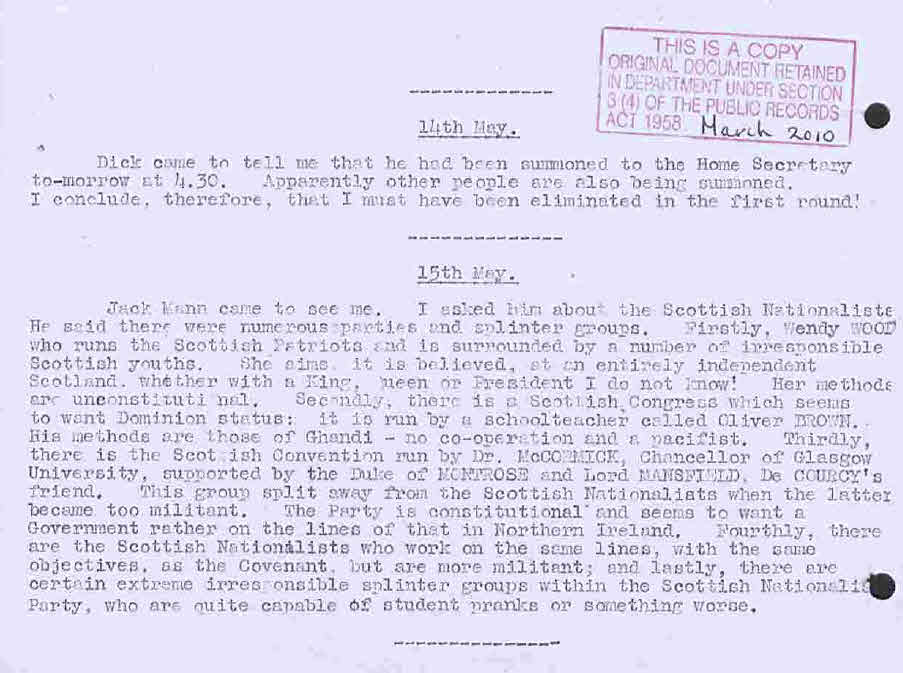

After sixty five hundred pages the record suddenly ends on May 15, 1953 as it began with Liddell mundanely describing a discussion about Scottish nationalist groups: Just days before he was sacked in the wake of the spy paranoia that still gripped the British establishment following the defection of Donald MacLean and Guy Burgess to Moscow two years earlier. Laconic as always, the only hint of his end was a May 14, 1953 entry that makes little sense without the fuller context. “Dick (Dick White) came to tell me that he had been summoned to the Home Secretary to-morrow at 4:30. Apparently other people are also being summoned. I conclude, therefore, that I must have been eliminated in the first round.”

Why he started writing the diary remains unclear even after all the years that have elapsed. Nigel West, editor of a two-volume collection of the diary, The Guy Liddell Diaries 1939-1942 and The Guy Liddell Diaries 1942-1945 (Routledge 2005, 2006) offers few clues.

West claims they were never meant for publication. Rather they were produced as a training aide for future MI5 executives interested in better understanding British wartime counterintelligence issues. If Liddell was ever asked about it no answers have surfaced. He died in 1957, just days after suffering a heart attack.

My feeling, after reading the journal, is that at some point his habit of recording the routine of meetings and events served as a release from the crushing pressures that he faced every day. At another level, l suspect that Liddell believed that a first-hand account produced from the heart of the British intelligence establishment would one day offer future generations of counterintelligence officers and the public useful lessons gleaned from past successes and mistakes. There seems to be no other conclusion. Liddell never benefited financially from the diary.

For those interested in selected topics I am sorry to report that the only index covers the first two years. Given the collection’s enormous range and the increasing pressures of the war further attempts at indexing were abandoned. For the next twelve years one will have to slog through the entire record. Don’t worry. It is worth it.

What does not emerge are insights into his personal life, evening events, weekend activities nor his opinion and feelings about his colleagues. The pages are sprinkled with entries about lunching with so and so at one of London’s many clubs or dinner with a colleague – but always confined to business. In the post war diaries, broken down by year, he starts his entries on the first day of the year with a tour de horizon that runs for a page or two and looks out around the world at what is happening. One benefit for researchers of the yearly diaries is the ease of concentrating on one particular time period. Another is the very few annoying redactions which make reading it so much more enjoyable.

Hint – jump ahead for fun to Volume 20, the Spring of 1951, and follow along with Liddell as he first learns about Donald Maclean’s treason and then watches helplessly as he and Guy Burgess disappear.

I urge you to take your time as you read. You will find, that by doing so, you will be better able to absorb the characters crossing the stage and the myriad of complex issues that regularly consumed Liddell’s time and energy. There are a lot of them. The diaries are a master class for students and professionals alike. Let Guy Liddell educate you. You are in for a real treat.

Guy Liddell Diaries

- VOL 1A__KV-4-185__28 AUG 39 – 26 NOV 39

- VOL 1B__KV-4-185__27 NOV 39 – 29 FEB 40

- VOL 2A__KV-4-186__1 MAR 40 – 7 AUG 40

- VOL 2B__KV-4-186__9 AUG 40 – 2 OCT 40

- VOL 3A__KV-4-187__3 OCT 40 – 3 APR 41

- VOL 3B__KV-4-187__4 APR 41 – 31 MAY 41

- VOL 4A__KV-4-188__2 JUN 41 – 25 OCT 41

- VOL 4B__KV-4-188__27 OCT 41 – 29 NOV 41

- VOL 5A__KV-4-189__1 DEC 41 – 12 MAR 42

- VOL 5B__KV-4-189__13 MAR 42 – 25 MAY 42

- VOL 6A__KV-4-190__26 MAY 42 – 22 SEP 42

- VOL 6B__KV-4-190__23 SEP 42 – 30 NOV 42

- VOL 7A__KV-4-191__3 APR 43 – 30 JUN 43

- VOL 7B__KV-4-191__1 DEC 42 – 2 APR 43

- VOL 8A__KV-4-192__1 JUL 43 – 30 AUG 43

- VOL 8B__KV-4-192__31 AUG 43 – 5 NOV 43

- VOL 8C__KV-4-192__6 NOV 43 – 30 NOV 43

- VOL 9A__KV-4-193__1 DEC 43 – 11 FEB 44

- VOL 9B__KV-4-193__12 FEB 44 – 29 APR 44

- VOL 10A__KV-4-194__1 MAY 44 – 18 JUN 44

- VOL 10B__KV-4-194__19 JUN 44 – 31 AUG 44

- VOL 11A__KV-4-195__1 SEP 44 – 13 OCT 44

- VOL 11B__KV-4-195__14 OCT 44 – 15 DEC 44

- VOL 11C__KV-4-195__16 DEC 44 – 31 DEC 44

- VOL 12A__KV-4-196__1 JAN 45 – 7 MAR 45

- VOL 12B__KV-4-196__19 MAR 45 – 29 MAY 45

- VOL 12C__KV-4-196__30 MAY 45 – 1 JUN 45

- VOL 13__KV-4-466__18 JUN 45 – 17 NOV 45

- VOL 14__KV-4-467__19 NOV 45 – 25 SEP 46

- VOL 15__KV-4-468__26 SEP 46 – 3 MAR 47

- VOL 16__KV-4-469__13 MAY 47 – 31 DEC 47

- VOL 17__KV-4-470__1948

- VOL 18__KV-4-471__1949

- VOL 19__KV-4-472__1950

- VOL 20__KV-4-473__1951

- VOL 21__KV-4-474__1952

- VOL 22__KV-4-475__1 JAN 53 – 15 MAY 53

You must be logged in to post a comment.